To access and purchase local meat, consumers have choices. One option is to buy a live animal from a livestock producer and have that animal processed at a custom-exempt, state-inspected or federally inspected facility. Rather than purchase a whole animal, consumers could instead pool their resources and split meat from an animal in halves or quarters. Buying a whole, half or quarter is considered a “bulk quantity” meat purchase.

Purchasing local meat in bulk quantities allows you to customize how your meat is cut and packaged. You can choose what’s best for your home, eating style, schedule and budget. Directly buying from farms also gives you an opportunity to support your local economy and know the farmer or rancher who raised the animal you purchase (Thilmany et al., 2020).

If you plan to buy an animal to have processed into packaged meat, then the process can present some learning curves. This publication can help you navigate that process in five steps.

- Identify desired meat products.

- Purchase animal from livestock producer.

- Find a processor that fits your needs.

- Understand your costs.

- Consider timing.

Step 1: Identify desired meat products

Consumers who buy meat in bulk should estimate how much meat to buy and consider what meat cuts they’d like the processor to make.

How much meat to buy

Before you purchase an animal to be processed, determine how much beef, pork, chicken, lamb or goat meat your family can consume in a three- to six-month period. When you pick up meat from the processor, it’s typically frozen. Freezing extends the shelf-life of meat; however, product quality declines the longer meat is stored (Qian et al., 2018). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services maintains a list of recommended food storage times.

Next, ensure you have enough freezer space to store the meat you purchase. Plan to have one cubic foot of freezer space for every 35 pounds to 40 pounds of meat (USDA, 1969). Space needs can vary, however, if the meat is cut into odd shapes.

What cuts to make

As you estimate how much meat you need, also consider the meat cuts you’re most likely to use. When processing a whole animal, you may receive cuts that are unfamiliar. Consider whether you want these cuts or ask the processor to convert cuts you’re less likely to use into ground meat. Request that the processor explain what cuts are available and approximate the quantity of each cut you’ll receive.

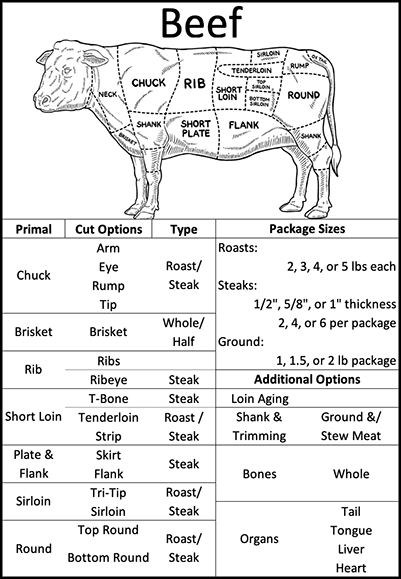

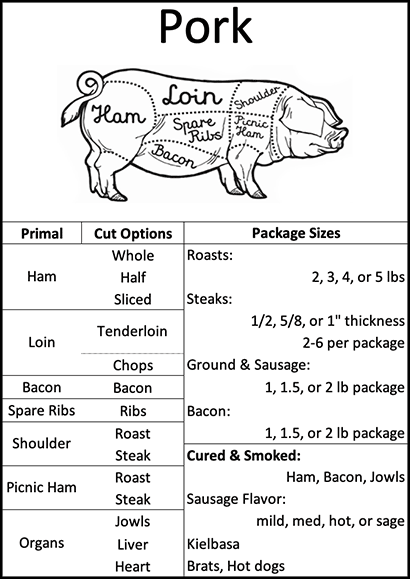

After you decide what cuts best meet your needs, you will fill out a “cut sheet” to give to the processor when your animal is delivered. In some cases, the processor will ask you questions and complete the sheet for you. The cut sheet will instruct the processor about what cuts to make from each primal along with steak thickness and roast size (also known as fabricating the carcass). Figure 1 provides an example of a beef and pork cut sheet.

Fabrication refers to creating the various cuts from the carcass to produce particular types of products. Primal or wholesale cuts are made first (Hui, Y.H., et al., 2012).

A cut sheet is used to record information such as how thick to cut steaks, what package portion sizes you’d like, what specific cuts you want from each primal (e.g., steaks or roasts), whether you prefer bone-in or boneless cuts and what specialty products you want the processor to make for you. Specialty products may include hot dogs, brats, premade burger patties and cured and smoked bacon and hams.

Step 2: Purchase animal from livestock producer

Purchasing local animals to process into meat requires connecting with local farms that sell finished animals. Farms throughout the state take pride in raising animals to sell directly to consumers like you.

Take your time to find an animal that meets your needs and expectations. Navigating this process for the first time can be challenging. However, these resources can help:

- Show Me Food — Hosted by MU Extension, this searchable database includes farms selling directly to consumers and butchers.

- Missouri Meat Producer Directory — From Missouri Farm Bureau, this directory organizes local meat producers into lists by county and city.

- Eat Wild — In this directory, you can find farms that produce grass-fed meat, eggs and dairy products.

- Local Harvest — Search for farms, community supported agriculture subscriptions and farmers markets by area.

To find local farms selling animals for slaughter, you can also check local advertisements and social media, or talk with friends, family and neighbors. An online search is likely to provide a list of potential options as well.

Step 3: Find a processor that fits your needs

If the farm selling your animal does not arrange processing or does not use your preferred processor, then you can make processing arrangements yourself. Before you choose a processor, call or visit to learn about the business’ services. Meat cuts, packaging and further processing options (e.g., curing and smoking) will vary by processor. Some processors offer value-added services such as longer meat aging times, multiple curing and smoking flavors or specialty products such as meat sticks and jerky.

Many small-scale local processors do not pay for advertising. Therefore, to find a processor near you, consider resources such as the following. All small meat processors that slaughter or butcher animals must register with the state’s Meat and Poultry Inspection Program, which is part of the Missouri Department of Agriculture (MDA), or the USDA Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS).

Processors register with a particular agency depending on the type of inspection program or inspection exemption that applies to them: a federal grant of inspection, a Missouri grant of inspection or a Missouri exemption of inspection — also called a custom exemption.

USDA inspected

Meat processed by a federally inspected processor can be sold at retail in any state and across state lines. FSIS provides a directory of all federally inspected facilities.

State inspected

Meat processed by a state-inspected processor can be sold at retail locations within Missouri. This includes Missouri restaurants, stores, farmers markets and other retailers. Buyers from other states may visit Missouri to purchase state-inspected meat. However, Missouri retailers may not sell state-inspected meat in other states or online to buyers in other states.

Custom exemption

At custom-exempt meat processing facilities, animals and meat don’t require state or federal inspection. These facilities may only provide custom butchering services to animal owners.

Meat processed at a custom-exempt facility is not eligible for retail sales, and it will be labeled “not for sale.” It can only be used by the person who owns all or a share of a live animal (i.e., half a beef) and that person’s household along with nonpaying guests and employees. The animal owner is the individual who owns the live animal at the time of slaughter.

To find a custom-exempt processor, call MDA’s Meat and Poultry Inspection Program at 573-522-1242, or refer to the directories available from the Missouri Association of Meat Processors or MU Extension’s Show Me Food database.

Step 4: Understanding your costs

When purchasing an animal for processing, you will pay for both the animal and processing that animal. These are separate transactions. You pay the livestock producer for the animal, and you pay the processor for slaughtering the animal and processing the meat.

Paying the producer

The producer will set the live animal’s price. Essentially, you pay the producer for raising and finishing the animal. Producers may sell animals at a price per pound of live weight or a price per head. The live weight is the weight of the live animal prior to slaughter.

Paying the processor

Your bill from the processor typically will include three types of costs: processing costs, slaughter and disposal fee and other additional processing fees.

Processors base processing costs on a price per pound of hanging weight — also known as the hot carcass weight. A hanging weight equals the animal carcass’ weight after removing the head, hide, blood and offal (internal organs). Remember, you will take home less than the hanging weight because fat and bones are included in this weight.

Using your animal’s live weight and hanging weight, you can determine the animal’s dressing percent, which is the percent of live weight that is hung. Calculate it as follows:

Dressing percent = [(hot carcass weight/live weight) × 100]

To approximate an animal’s hanging weight, you can also use an average dressing percent, shown in Table 1. Keep in mind, however, that your animal’s exact dressing percent will likely vary. Factors that affect dressing percent include age, gender, breed, live weight and amount of fill. To estimate hanging weight, use this formula:

Estimated hanging weight = live weight × average dressing percent

Table 1. Average dressing and take-home percent for the hot carcass of a lean, non-pregnant female or castrated male animal at market weight with a clean, dry hide (Hui, Y.H., et al., 2012).

| Species | Average dressing percentage | Average take home percentage of liveweight |

|---|---|---|

| Beef cattle | 62 | 35 |

| Hogs | 73 | 36 |

| Sheep | 52 | 25 |

For example, if you purchase an 1,100-pound beef steer, you could expect to take home approximately 385 pounds of meat.

Expect processors to charge a slaughter and disposal fee. This fee compensates the processor for discarding the animal’s head, hide, blood and offal — a term used to describe the unused organs.

Depending on the processor, you may incur other additional fees for packaging (vacuum packaging is more expensive than butcher paper); specialty meats such as brats, hot dogs and premade burger patties; and cured and smoked meats. Typically, processors base these specialty product fees on a price per pound of these products’ raw weight.

Totaling your costs

The formulas shown in Figure 2 will help you calculate your cost to purchase and process an animal. Talk with your farmer and processor to get current pricing. Also, you can use the average dressing percentage above to estimate pounds hanging weight.

Figure 2. Worksheet for calculating total and average cost of local meat.

Step 5: Consider timing

Timing is important throughout this process. Keep in mind these four timing considerations as you plan to make a processing appointment and when to pick up your meat.

Schedule processing appointment in advance

Take care when scheduling the slaughtering and processing appointment. When asking processors for available processing dates, only consider scheduling an appointment time that coincides with when the animal will be ready to butcher. This timeline can vary based on the animal’s expected growth rate. In some cases, the animal available may not fit in the processor’s schedule.

To give you the best chance of securing an appointment, you or the livestock producer should contact the processor well in advance of the desired processing appointment time. In some cases, you may need to check several months or even a year ahead.

Be prepared for the processing appointment

Know drop-off and pickup procedures. Be on time for your appointment; this helps you to build a good relationship with your processor. If you need to cancel or change your appointment, then contact your processor as soon as possible. The processor may be able to rebook an appointment.

When estimating a pickup date, account for processing time

Processing involves multiple steps including chilling and aging the carcass, cutting the meat, creating specialty cuts, packaging meat and freezing meat. The time needed for these steps is known as total processing time. Processors use varying hanging and aging times, so contact your processor to know how much time will elapse between delivering the live animal and picking up your meat.

Don’t miss your pickup date

Your processor has limited space for storing processed meat, so pick up meat soon after it’s ready. Talk with your processor if you experience a delay and cannot pick up your meat right away. Processors may store your meat for a short time, and they may charge storage fees if you don’t pick up processed meat on time.

Before the pickup date, double-check you have enough freezer space ready to store your meat. Also, consider taking boxes or large coolers when you pick up meat. They help keep your meat cool during the trip home.

References

- Hui, Y.H., Aalhus, J.L., Cocolin, L., Guerrero-Legarreta, I., Nollet, L.M., Purchas, R.W., Schilling, M.W., Stanfield, P. & Xiong, Y.L. (2012). Handbook of Meat and Meat Processing (2nd edition). CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group.

- Quin, S., Li, X., Wang, H., Sun, Z., Zhang, C., Guan, W., & Blecker, C. (2018). Effect of sub-freezing storage (-6, -9, and -12 °C) on quality and shelf life of beef. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 53(9), 2129–2140.

- Thilmany, D., Canales, E., Low, S., & Boys, K. (2021). Local food supply chain dynamics and resilience during COVID-19. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(1), 86–104.

- USDA. (1969). How to Buy Meat for Your Freezer (PDF). National Agriculture Library, Consumer and Marketing Service Home and Garden Bulletin No. 166.