Warm-season grasses are important because they provide high-quality forage during the hot summer months when cool-season grasses are less productive. These grasses are drought-tolerant, help reduce soil erosion and provide habitat for wildlife. With rising concerns over increasing fertilizer costs, weed pressure, nitrate and prussic acid risks, and unpredictable weather, especially drought, livestock producers in Missouri face several challenges in maintaining productive pastures in the summer. When warm-season grasses are unavailable, relying on commercial feed like soybean meal can significantly increase livestock production costs. This increase in feed costs can strain the budget of livestock operations, making warm-season grasses a cost-effective and sustainable option for forage. Utilizing warm-season grasses strategically can reduce reliance on commercial feed, lowering costs and improving profitability. Simple management strategies can boost forage yield and quality, enhance pasture resilience, and further lower costs. Here are some key tips for Missouri livestock producers on managing warm-season grasses effectively.

Understanding your soil dynamics

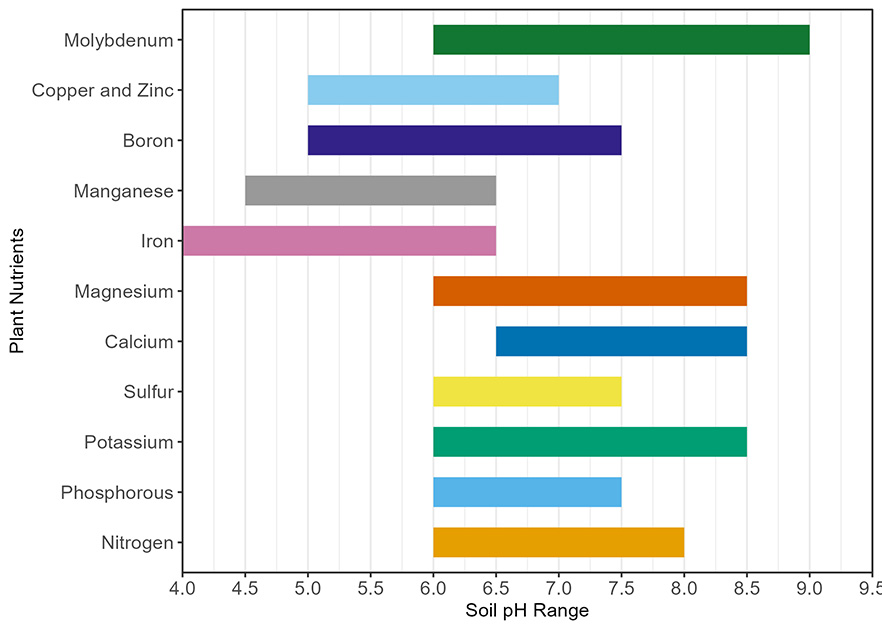

Understanding soil dynamics is crucial because it directly impacts crop productivity, soil health, and management practices. By knowing soil properties such as texture, structure, nutrient content, and pH levels, farmers can make informed decisions about crop selection, planting, fertilization, irrigation, and pest management. Soil texture affects pasture growth by influencing water retention, infiltration, and nutrient availability. For example, sandy loam soil has moderate water retention, high infiltration and drainage, and moderate nutrient availability, whereas clay loam soil has high water retention, low infiltration and drainage, and high nutrient availability. Likewise, soil pH significantly influences nutrient availability and uptake by plants. Nitrogen (N) is most available in slightly acidic to neutral soils. Phosphorus (P), however, becomes less available in highly acidic soils due to fixation with iron and aluminum, and in alkaline soils due to fixation with calcium. Potassium (K) is generally unaffected by pH but can be limited in extreme conditions. Micronutrients like iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu) are more available in acidic soils but become deficient in alkaline conditions (Figure 2). In contrast, molybdenum (Mo) becomes more available as pH increases. Maintaining soil pH between 6.0 and 7.0 ensures optimal nutrient availability for plant growth. Soil pH also influences weed populations. The 2015-2016 Missouri Pasture survey revealed that a 1-unit increase in soil pH resulted in approximately 4,100 fewer weeds per acre. Additionally, each 0.1 ppm increase in phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) led to reductions of 162 and 12 weeds per acre, respectively. Hence, understanding soil dynamics helps optimize crop yields, reduce costs, and minimize environmental impacts.

Tips: Properly balanced soil fertility and pH can enhance pasture resilience and productivity. Hence, test your soil every 2 to 3 years. Based on the test results and recommendation, you can apply fertilizer and/or lime that meets the specific needs of the forage you are growing.

Selecting the right warm-season grasses

Selecting the right warm-season grasses is important for Missouri because they thrive in the hot summers, reduce feed costs, withstand drought, support wildlife, and promote sustainable land management. Missouri’s climate is well-suited for several warm-season grasses, each with its own advantages and management requirements (Table 1).

Table 1. List of summer forages and their tentative planting time in Missouri

| Forage | Planting time | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Perennial/Native Warm-Season Grasses | ||

| Big bluestem | April to June | A highly nutritious native grass with excellent drought tolerance but requires a longer time to establish and careful grazing management to prevent overgrazing. |

| Indiangrass | April to June | Known for its palatability and high yields but can become stemmy and less palatable if not properly managed. |

| Switchgrass | April to June | A highly productive species that provides good summer grazing and erosion control and can be used for biofuel production. It can be overly aggressive in spreading and may require controlled grazing or mowing. |

| Eastern gamagrass | April to May | High-quality forage with good regrowth potential but slow to establish and sensitive to overgrazing. |

| Little bluestem | April to June | A native, drought-tolerant grass that provides good forage quality but has lower yields compared to other native warm-season grasses. Best suited for well-drained soils. |

| Bermudagrass | Late March to June | A perennial, non-native grass that is highly drought-tolerant and provides excellent ground coverage to prevent soil erosion. Requires high nitrogen fertilization and is susceptible to winter kill. |

| Zoysiagrass | April to June | A non-native, drought-tolerant grass that provides excellent ground cover and erosion control. Primarily used for lawns but can serve as forage in some cases. |

| Annual Warm-Season Grasses | ||

| Sorghum-sudan grass hybrids | Late April to July | Known for rapid growth and high biomass production. Used for hay or silage but requires careful management to avoid prussic acid toxicity. |

| Forage sorghum | May to July | Grows quickly and produces high yields, making it excellent for silage or grazing. Requires proper management to avoid prussic acid toxicity. |

| Millet (Pearl or Foxtail) | May to July | Quick-growing summer annual used for forage or grain production. Drought-tolerant with high forage quality but lower yield than other warm-season grasses. |

| Buckwheat | May to August | A fast-growing annual that can be planted as a cover crop or forage. Improves soil health with deep rooting but is not highly drought tolerant. |

| Corn silage | Late April to early June | Valued for its high-energy content and digestibility. Provides excellent yields and a reliable feed source during fall and winter when pastures are less productive. |

| Note: The planting time of the above-mentioned warm-season grasses is tentative and is largely depends on temperature. They begin to germinate when the soil consistently reaches 65°F and above. Northern Missouri tends to warm up later in spring, so planting may be delayed by 1-2 weeks compared to Southern Missouri. | ||

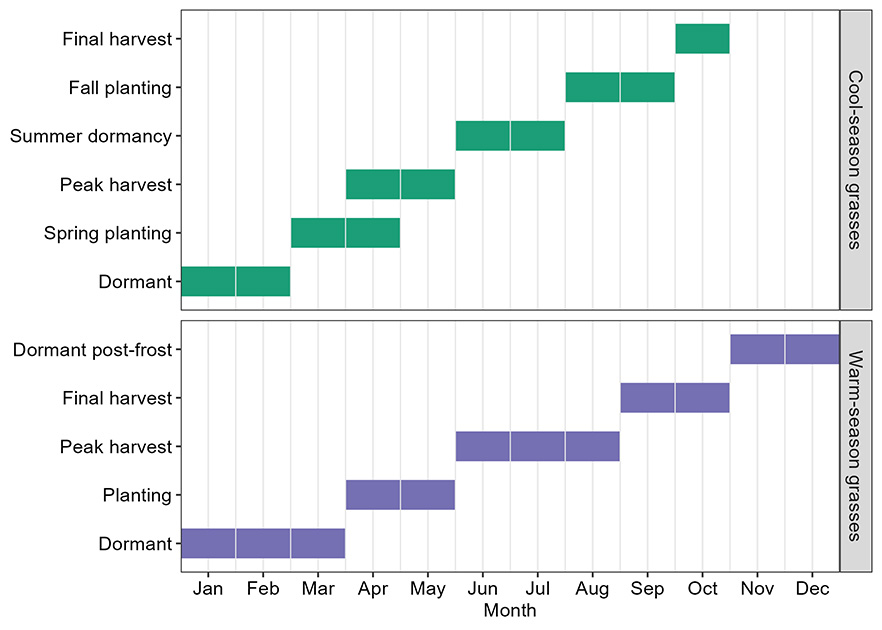

Note: The timeline may vary with location and weather variability. For example, Northern Missouri may have shorter warm-season windows than southern regions. Drought or early frost can shift timelines.

Tips: Choose grasses and their varieties that match your local climate, soil type and grazing goal. When selecting the right warm-season grass for Missouri, consider climate adaptability, soil type, drought tolerance, maintenance needs, pest and disease resistance, intended use, and growth habit. For example, if drought tolerance and long-term pasture system is a priority, Big bluestem and Switchgrass are excellent choices. For a more intensive, short-term feed solution, Sorghum-Sudan hybrids could be a better fit, particularly if rapid biomass production is needed during the summer months. Plant warm-season grasses in late spring and summer, and cool-season grasses in spring and fall for optimal pasture productivity. To mitigate prussic acid risks when using sorghum-sudan hybrids, avoid grazing young regrowth under 18 inches and gradually introduce cattle to these pastures. For additional information on warm-season annual forages, visit the MU Extension publication G4661, Warm-Season Annual Forage Crops. For details on seeding rates, planting dates, and planting depths for common Missouri forages, refer to MU publication G4652, Seeding Rates, Dates and Depths for Common Missouri Forages.

Incorporating legumes for enhanced forage quality

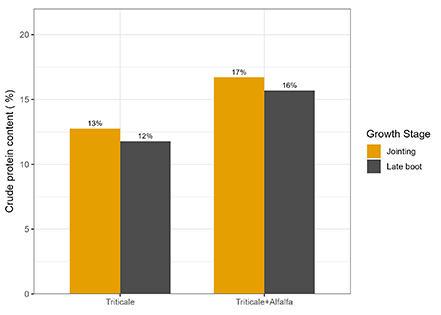

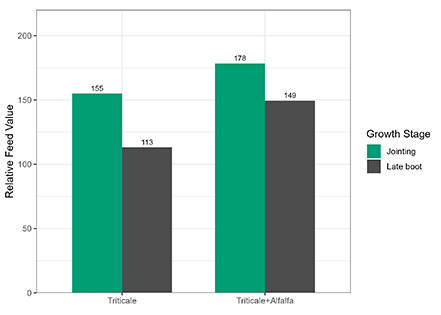

Integrating legumes such as white clover, red clover, or alfalfa into warm-season pastures is one of the most effective ways to enhance their productivity and quality. Legumes offer several advantages that make them valuable additions to pasture systems. Firstly, legumes have the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, typically ranging from 50 to 80 pounds per acre. This natural nitrogen fixation reduces the need for synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, thereby lowering input costs and improving soil fertility over time. Additionally, mixing legumes with grasses can significantly improve forage quality. The presence of legumes can increase crude protein levels by 3 to 5 percentage points and relative feed value by 20 to 40 points compared to grass-only forages (Figure 4), which in turn enhances livestock body weight gains. This improvement in forage quality is crucial for maintaining healthy and productive livestock.

Legumes also contribute to an extended grazing season. They often grow during periods when warm-season grasses may be less productive, providing a more consistent forage supply throughout the growing season. This extended availability of high-quality forage helps ensure that livestock have access to nutritious feed even during less favorable growing conditions. Moreover, legumes offer substantial soil health benefits. They improve soil structure and increase organic matter content, which enhances water infiltration and reduces erosion. These improvements in soil health contribute to the overall sustainability and resilience of pasture systems.

Tips: When establishing a legume-grass mixed pasture, ensure proper seeding rates and soil pH (6.0–7.0 for most legumes). Consider incorporating 15-20% legumes in your pasture. White clover is a popular choice for its adaptability and persistence in mixed stands. Producers seeking summer cover crops, sunn hemp, lespedeza, cowpea, and forage soybean can be the excellent choice, each yielding 2–4 tons of hay per acre. Sunn hemp grows fast, cowpea thrives in heat, and forage soybean offers a dual benefit of nutritious forage and soil enrichment. Regularly monitor legume stands to ensure proper balance with grasses, as excessive legumes can lead to bloat in cattle.

Table 2. Forage yield, crude protein, and feed value of grasses, legumes, and mixed stands

| Forage | Forage type | Dry matter yield (Ton/Acre) | Crude protein (%) | Total digestible nutrients (%) | In Vitro Dry Matter Digestibility (IVDMD) | Relative feed value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grasses | ||||||

| Timothy | Cool-season grass | 3–4 | 8–12 | 52–58 | 65–70 | 80–100 |

| Bermudagrass | Warm-season grass | 3–5 | 7–10 | 48–53 | 60–65 | 75–90 |

| Tall Fescue | Cool-season grass | 2–3 | 9–12 | 50–55 | 65–80 | 80–95 |

| Orchardgrass | Cool-season grass | 4–5 | 10–14 | 55–60 | 70–75 | 90–110 |

| Big Bluestem | Native warm-season grass | 4–6 | 7–10 | 50–55 | 60–65 | 75–90 |

| Indiangrass | Native warm-season grass | 4–6 | 8–12 | 52–58 | 55–65 | 80–100 |

| Switchgrass | Native warm-season grass | 3–6 | 6–9 | 50–54 | 60–70 | 70–85 |

| Eastern Gamagrass | Native warm-season grass | 5–8 | 9–13 | 55–60 | 70–75 | 85–105 |

| Legumes | ||||||

| Alfalfa (Irrigated) | Legume | 5–7 | 20–24 | 62–67 | 80–90 | 160–190 |

| Alfalfa (Rainfed) | Legume | 3–5 | 18–21 | 58–62 | 75–85 | 140–170 |

| White Clover | Legume | 2–3 | 18–24 | 65–70 | 75–85 | 170–200 |

| Grass-Legume Mixtures | ||||||

| Alfalfa + Grass (N Fertilized) | Mixed | 5–6 | 16–20 | 60–65 | 75–85 | 130–160 |

| Alfalfa + Grass (No Nitrogen) | Mixed | 5–5 | 14–18 | 58–62 | 70–85 | 120–150 |

| Timothy + White Clover | Mixed | 4–5 | 12–16 | 58–62 | 70–80 | 110–140 |

| Tall Fescue + White Clover | Mixed | 3–4 | 14–18 | 58–63 | 70–80 | 120–150 |

| Native Grasses + White Clover | Mixed | 3–5 | 12–16 | 55–60 | 70–75 | 100–130 |

| Note: The values in the table are based on the research findings and author's observation which may vary on location, crop varieties, soil type and management practices. | ||||||

Fertilizer management

Several research studies have found that 40-60% of nitrogen (N) fertilizer is lost through volatilization, leaching, denitrification, and surface runoff, without being utilized by plants. The 2015-2016 Missouri pasture survey conducted by the University of Missouri found that 80% of the 46 pastures surveyed had low or very low soil phosphorus (P) levels, while 37% had low or very low soil potassium (K) levels. The average soil pH in the surveyed pastures was 5.8. Furthermore, the University of Missouri On-Farm Nitrogen Plus/Minus Strip Trials (2016–2023) found that 10 of 18 farmers lost money by applying less nitrogen. Additionally, half of the farmers in the study benefited from a higher nitrogen rate than they initially applied, suggesting that many are underapplying nitrogen. Thus, applying the right amount of fertilizers, based on soil testing and recommendations, at the right time and place helps reduce production costs and environmental risks while optimizing pasture health and productivity. An efficient method for applying nitrogen fertilizer is through split applications.

- 50% in mid spring (April) at green up

- 50% in mid-summer (June)

- Phosphorus and potassium should be applied during planting or green up stage based on soil test recommendations.

Tips: Conduct soil tests every 2–3 years and apply fertilizers and lime based on soil test report. Legumes can replace 50–80 pounds of nitrogen per acre, reducing fertilizer expenses. Applying nitrogen stabilizers can help reduce nitrogen losses and improve fertilizer efficiency.

Weed management

Weed is the major concern of Missouri livestock farmers. Common ragweed, horsenettle, pigweeds, ironweed species, nutsedge spp, annual fleabane, vervain, yellow foxtail, broadleaf plantain, virginia copperleaf and dandelion are some of the common weeds found in pastureland in Missouri. Some of them such as horsenettle, ironweeds, virginia copperhead can pose health risks due to their toxicity or digestive issue. Weed management is crucial in warm-season grass pastures, especially during establishment, as these grasses grow slowly in their early stages, making them vulnerable to weed competition. During the first 6–8 weeks of grass establishment, weeds can outcompete young grasses for nutrients, water, and sunlight, reducing pasture productivity. Effective weed management during this period is crucial to reduce competition and enhance pasture productivity. Here are some comprehensive strategies combining cultural, mechanical, biological, and chemical control methods:

Cultural practices

- Proper fertilization: Conduct soil tests and apply fertilizers based on the results to promote healthy grass growth, which can outcompete weeds.

- Grazing management: Avoid overgrazing to prevent weakening the grass and creating bare spots where weeds can establish. Rotate grazing areas to allow grasses to recover.

- Crop selection: Choose crops like sorghum-sudangrass, known for excellent weed control and high biomass production, and eastern gamagrass, which establishes a dense canopy that effectively outcompetes many weed species.

Mechanical control

- Mowing: Regular mowing helps suppress certain weed species by preventing them from setting seed. However, repeated applications may be necessary for effective control. Maintain a height of around 8 inches for warm-season grasses.

- Thatch management: Remove excess thatch to reduce weed seed germination. This can be done through mechanical means or controlled burning, depending on local regulations and conditions.

Biological control

- Musk Thistle Weevils: Utilize biological control agents like musk thistle weevils, which have shown success in reducing specific weed populations.

Chemical control

- Pre-emergent herbicides: Apply pre-emergent herbicides in early spring to prevent weed seeds from germinating. This is particularly effective against annual weeds like crabgrass.

- Post-emergent herbicides: Use post-emergent herbicides to control existing weeds. These are best applied when weeds are actively growing, typically in late spring or early summer. Ensure herbicides are applied at the right growth stage for optimal results.

Tips: Proper weed management not only boosts pasture productivity but also enhance forage quality, improve livestock grazing efficiency. Hence, inspect your pastures regularly for weed infestations and address them promptly. Early detection and treatment are crucial for effective weed management. Grazing at appropriate heights (starting when the grass is 12 to 18 inches tall and stopping when it is grazed down to 6 to 8 inches) and rotational grazing can help suppress weed populations by maintaining dense grass cover.

Implementing rotational grazing

Rotational grazing offers numerous benefits, including improved forage quality, enhanced soil health, increased stocking rate, better manure distribution, reduced weed pressure, and lower parasite loads.

- Increased forage utilization: Rotational grazing ensures more even forage utilization, reducing waste and improving overall pasture productivity. This practice can improve forage availability by 30–50%.

- Higher stocking rates: Well-managed rotational systems support 20–30% more livestock per acre.

- Improved soil health: Reduces compaction, enhances water infiltration, and improves nutrient cycling.

- Prevent overgrazing: Allowing grasses to recover between grazing cycles promotes root growth and regrowth, leading to more resilient pastures. Maintaining stubble heights (e.g., 8–10 inches for Big bluestem) ensures regrowth.

- Enhanced manure distribution: Animals spread nutrients more evenly across paddocks, reducing soil degradation in high-traffic areas.

Tips: Rest paddocks for 6–8 weeks between grazing cycles and aim for 1–2 animal units per acre based on forage availability.

Optimizing hay and forage harvesting

Timely harvesting is crucial for maintaining forage quality and minimizing losses. Warm-season grasses can be harvested for hay, typically in July or August when nutrient levels are optimal. To ensure high-quality hay:

- Cut at the right height: Cut warm-season grasses at 18–24 inches, leaving a minimum of 6 inches of stubble for regrowth. Using a conditioning mower can speed up drying time and reduce the risk of rain damage to cut forage.

- Consider baleage: Baleage preserves the forage, maintaining its quality, extending its shelf life and reduce weather-related risks during haymaking.

Tips: Avoid cutting too late in the season, as forage quality declines as grasses mature. Research shows that harvesting at the early boot stage retains higher protein and digestibility.

Preparing for drought and extreme weather

Missouri’s climate is prone to drought and extreme weather events, which can stress warm-season grasses. Farmers should develop drought management plans, including stockpiling forage and maintaining emergency feed reserves, to sustain livestock during dry periods. To build resilience:

- Drought-resilient species: Choose drought-tolerant species like Big Bluestem and Bermudagrass.

- Soil moisture conservation: Use no-till drills for seeding to conserve soil moisture and improve establishment success.

- Emergency forage options: Keep summer annuals like Sorghum-Sudangrass or Pearl Millet as backup forage options during drought conditions.

- Deep-rooted species: Choosing deep-rooted forages enhances drought resistance and long-term pasture health.

Tips: Diversifying your forage base with both warm-season grasses and legumes can provide a buffer against weather-related forage shortages.

In summary, effective management of warm-season grasses requires a combination of species selection, strategic fertilization, rotational grazing, and weed control. By incorporating legumes into pasture systems, producers can enhance soil fertility, improve forage quality, and reduce input costs. With proper planning and management practices, warm-season grasses can significantly improve forage yield, quality and profitability of livestock operations in the region.

For more information, please contact Rudra Baral, Agronomy Specialist, University of Missouri Extension via email at rudrabaral@missouri.edu or call at (573) 369-2394.

References

Ball, D. M., Hoveland, C. S., & Lacefield, G. D. (2015). Southern forages: Modern Concepts for Forage Crop Management.

Baral, R. B. (2023). Assessing yield, quality, water use efficiency and profitability of forage crops in rainfed agricultural management systems. Kansas State University.

Baral, R., Jagadish, S. K., Hein, N., Lollato, R. P., Shanoyan, A., Giri, A. K., Kim, J., Kim, M. & Min, D. (2023). Exploring the impact of soil water variability and varietal diversity on alfalfa yield, nutritional quality, and farm profitability. Grassland Research, 2(4), 266-278.

Barnhart, S. K., & Hintz, E. (1981). Warm-season grasses for hay and pasture. Cooperative Extension Service, Iowa State University.

Barrow, N. J., & Hartemink, A. E. (2023). The effects of pH on nutrient availability depend on both soils and plants. Plant and Soil, 487(1), 21-37.

Begna, S., Putnam, D., Wang, D., Bali, K., & Yu, L. (2024). Yield and nutritive values of semi-and non-Fall dormant alfalfa cultivars under late-cutting schedule in California’s Central Valley. American Journal of Plant Sciences, 15(10), 858-876.

Chapman, D. F., Lee, J. M., Rossi, L., Edwards, G. R., Pinxterhuis, J. B., & Minnee, E. M. K. (2016). White clover: the forgotten component of high-producing pastures? Animal Production Science, 57(7), 1269-1276.

Hall, M. (2000). Orchardgrass.

Harper, C. A., Bates, G. E., Gudlin, M. J., & Hansbrough, M. P. (2011). PB1746 A landowner's guide to native warm-season grasses in the Mid-South (No longer available online.).

Jones, T. (2024). Considerations for managing alfalfa hay in the face of insecticide resistance: demonstration and discussion. University of Wyoming Extension.

Kallenbach, R., Roberts, C. A., & Hurley, G. B. (2001). Warm-Season Annual Forage Crops. MU Extension, University of Missouri--Columbia.

Lory, J. (2024, December 4–5). Findings from the University of Missouri On-Farm Nitrogen Plus/Minus Strip Trials (2016–2023). Presented at the MU Crop Management Conference, Columbia, MO.

Lowe II, J. K., Boyer, C. N., Griffith, A. P., Waller, J. C., Bates, G. E., Keyser, P. D., Keyser, J. A. Larson & Holcomb, E. (2016). The cost of feeding bred dairy heifers on native warm-season grasses and harvested feedstuffs. Journal of dairy science, 99(1), 634-643.

McDonald, I., Baral, R., & Min, D. (2021). Effects of alfalfa and alfalfa-grass mixtures with nitrogen fertilization on dry matter yield and forage nutritive value. Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 63(2), 305.

Pierce, R. A., Kallenbach, R. L., Reinbott, T., Wright, R. L., & Udawatta, R. P. (2017). Mixtures of native warm-season grasses, forbs and legumes for biomass, forage and wildlife habitat. University of Missouri Extension.

Redfearn, D., & Rice, C. (2011). Bermudagrass pasture management. Oklahoma State University Extension.

Roberts, C. A., & Gerrish, J. (2001). Seeding Rates, Dates and Depths for Common Missouri Forages. MU Extension, University of Missouri--Columbia..

Rushing, J. B., Lemus, R. W., White, J. A., Lyles, J. C., & Thornton, M. T. (2019). Yield of native warm‐season grasses in response to nitrogen and harvest frequency. Agronomy Journal, 111(1), 193-199.

Tahir, M., Li, C., Zeng, T., Xin, Y., Chen, C., Javed, H. H., Yang, W. & Yan, Y. (2022). Mixture composition influenced the biomass yield and nutritional quality of legume–grass pastures. Agronomy, 12(6), 1449.

Tahir, M., Wei, X., Liu, H., Li, J., Zhou, J., Kang, B., Jiang, D. and Yan, Y. (2023). Mixed legume–grass seeding and nitrogen fertilizer input enhance forage yield and nutritional quality by improving the soil enzyme activities in Sichuan, China. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1176150.