Editor’s note

This publication is also available in Spanish. (Esta publicación también está disponible en español.)

Small acreage owners often want to earn income from their land. Income goals may range from “making a little extra” to operating a full-time business that provides significant household income.

Land can generate income in many ways. The focus here is on agriculture and related enterprises. Rather than a “how-to” guide, or a step-by-step business planning guide, this publication focuses on important questions to ask as you consider ways to earn income using your small acreage.

Interest in small acreage enterprises is partly tied to rebounding small farm ownership. Approximately one-third of Missouri farms — which produce $1,000 or more in agricultural products per year — are less than 50 acres in size (USDA Census of Agriculture, 2017). The number of Missouri farms less than 10 acres grew 57% from 2012 to 2017. Owners of slightly larger land tracts, 10 to 50 acres, showed a 4% increase during that time period.

What is your goal?

Small acreage landowners may launch enterprises to become a primary income source. Other reasons landowners develop businesses include farm diversification, supplemental income, stewardship, self-sufficiency, and enjoyment and lifestyle.

Primary income source

Some small acreage landowners are looking for an enterprise as their primary income source. These enterprises should be capable of producing high value using limited acreage. A potentially greater value of production usually corresponds with larger initial investments, more marketing, greater risk, or all of these. Examples of such enterprises include high-value greenhouse crops and perennial fruit crops.

Farm diversification

Small acreage enterprises may spin off from an existing, larger farm. Consider a farmer whose child or other relative wants to earn a living from the farm but the existing farm is unable to provide additional income. The son, daughter or other relative may add a small acreage enterprise to generate income. That enterprise may use some of the farm’s equipment or other existing resources.

Supplemental income

A small acreage could provide a landowner with a “second job” or supplemental income. Small acreage owners might also draw on supplemental income to help offset costs of owning and improving their land.

Stewardship of land/heritage

Some small acreage enterprises begin as a way to manage family-owned land. Common examples in Missouri include timber management or livestock production on an extended family’s “hunting ground.” People possessing skills, experiences or knowledge from growing up on or near a farm might also pursue an acreage-based business to connect with their rural roots.

Self-sufficiency

Many Missourians are interested in providing for their own basic needs through activities like growing and preserving their own food. This way of life is often described as “homesteading.” Homesteading activities may be a starting point for a farm or food business.

Enjoyment and lifestyle

Some small acreage owners develop a business from a hobby, which is a pursuit started for pleasure rather than income. An enterprise may grow beyond a hobby but may still supply landowners with either personal enjoyment or a preferred lifestyle. Many people operating businesses on small acreages may value the lifestyle, satisfaction and independence they find in different aspects of the business enterprise.

What should I produce?

Many enterprises are possible for small acreages in Missouri. Figure 2 lists some major enterprise categories and examples of specific enterprises. These are not all-inclusive lists. Investing the time and resources needed for a well-crafted business plan will guide you through questions specific to your possible enterprise. The following are important considerations for some enterprises possible on Missouri’s small acreages.

Livestock and poultry

Raising animals appeals to many Missouri acreage owners. Although small acreages have some natural limitations, there are many feasible livestock enterprises. These include traditional animal agriculture, like cow-calf herds, to niche production, like fiber from sheep and goats. These are some questions to consider before investing in livestock or poultry:

- Is there enough acreage to sustain livestock that will generate the desired level of profit?

- In order to start raising animals, what are the necessary investments or improvements in fencing, water, buildings or infrastructure?

- Do I have the basic animal production skills and knowledge needed for this enterprise?

- Will any necessary processing be provided on-farm or outsourced to another firm? To whom?

Agritourism

The Missouri Revised Statutes define agritourism as “any activity which allows members of the general public for recreational, entertainment, or educational purposes to view or enjoy rural activities, including but not limited to farming activities, ranching activities, or historic, cultural, or natural attractions.” Missouri is home to a range of agritourism activities, from pick-your-own farms to wineries, on-farm festivals to corn mazes.

Most agritourism activities involve inviting customers onto private property. Small acreage owners interested in agritourism should realize they (or their employees) will need the “people skills” necessary for interacting with the public. Managing risk, especially potential liability, is another area that cannot be ignored. These are important questions to consider for an agritourism enterprise:

- What are the liability risks and insurance needs for the agritourism enterprise?

- What additional labor will be needed to staff the enterprise?

- What are the land use and tax implications if using the acreage for agritourism?

Horticulture and nursery crops

Fruit, nuts, vegetables and other horticultural crops are very popular for production on rural and urban acreage. Production systems include open-field production, high tunnels and greenhouses or other controlled environment agriculture. Many of these enterprises have high labor needs and defined production seasons.

Horticultural crops often deliver higher returns, per acre or square foot, than agronomic crops like corn and soybeans. However, potentially higher returns can bring greater risks in producing and marketing horticultural crops. These are some of the important questions when considering horticultural enterprises:

- What market channels will I use to sell crops?

- Will selling prices return adequate profitability?

- What equipment or infrastructure are required for the business?

- What is the production season and perishability of the crops?

- What are the labor requirements?

Forest products

Small acreages can be ideal for producing many niche and specialty products. Examples of these in Missouri include timber and non-timber forest products like shade-grown mushrooms, woodland wreaths and handcrafted goods made from products gathered or grown on the acreage.

Markets for specialty and niche products can be ill-defined, and the local demand for these goods could be easily met by a single producer. These are important questions when considering a forest product enterprise for a small acreage:

- What are your plans for forest stewardship and how would they be affected by this enterprise?

- What is the likely quantity demanded and selling price of the product?

- Are there regulations that apply to the sale and/or processing of the product?

- Is this product best produced and sold by itself, or are there other products that can accompany it?

Value-added foods and products

Value-added agriculture, food and forestry products capture additional value for the producer. Producers do these two things to add value to their production:

- Convert a raw commodity into a product or do something to make the commodity more valuable.

- Capture the value created at final sale.

Adding value is important for profitability when enterprises cannot sell large quantities of products at small profit margins. These are a few of the many questions to answer about value-added enterprises:

- What is the specific way that you will add value to a product?

- What is the market — how much of the product can you sell at what price?

- What regulations will you need to follow?

- What is the cost of the supplies and equipment needed to add value?

Specialty field crops

Specialty field crops include agronomic crops not grown as widely as commodity corn and soybeans. Specialty field crops can be used to diversify and expand existing row crop operations and to increase profitability for beginning producers without access to larger acreages. These are some questions when considering specialty agronomic crops:

- What new equipment is needed?

- Does the price premium justify production?

- Are new crop storage or handling facilities needed?

- Do I need a contract for production or will I process the crop into a final product?

Creating whole farm synergy

Small farms often enhance their profitability and resilience by engaging in multiple enterprises that enhance or complement one another. It is important to select enterprises that are a good match for the available resources. Selecting complementary enterprises creates an opportunity for better resource allocation and may also improve cash flow and financial profitability. Examples of complementary, synergistic enterprises include:

- Integrating livestock and crops where one waste product becomes another’s feedstock

- Seasonal diversification, such as winter timber stand improvement and sawmilling complementing seasonal pastured poultry and turkey production

- Stacking enterprises by using practices like intercropping — practice of growing two or more crops in close proximity — or multi-species grazing

- Diversifying annual crops with perennial crops

Business planning

Whatever your goal is for a small acreage enterprise, the process of business planning will help guide you. Business planning may also help prevent you from starting an enterprise that will not meet your goals.

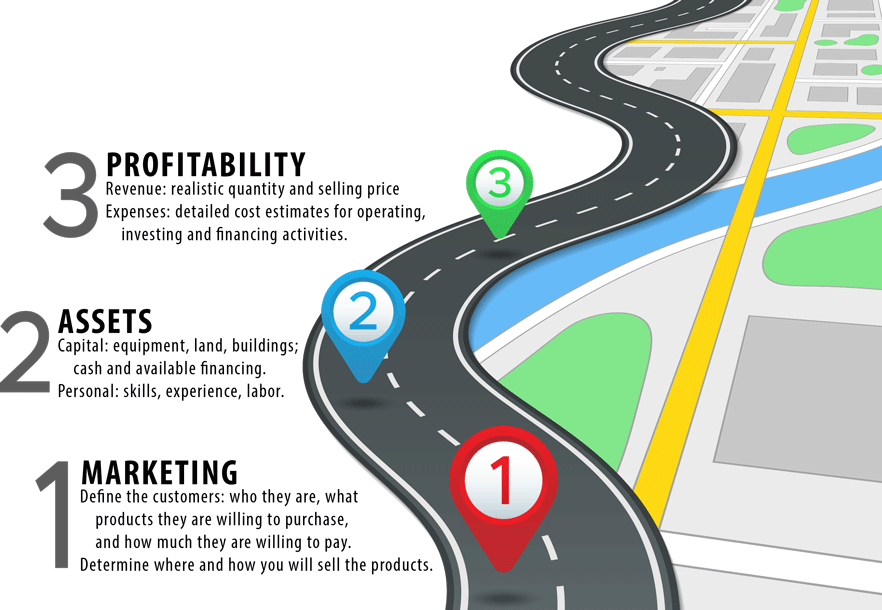

We will now look at marketing, assets and profitability. These are three of the most important aspects of small acreage business planning and may be referred to as the Business Plan MAP (Figure 3).

1. Marketing

There must be a market — a demand for a product at a certain price — for the product you aim to produce on your small acreage. Successful businesses of any size develop a marketing plan before starting production. Forgetting or ignoring markets before beginning production is a common pitfall for small enterprises.

Some farm products have well-established markets. Many farm products are commodities — products that are identifiable, interchangeable and easily bought and sold. Consider beef cattle: Cattle buyers at livestock auctions across Missouri regularly purchase feeder cattle of certain weights for prices that rise and fall based on regional and national market trends. Commodity producers are often price takers. Profits in commodity agriculture are typically greater for higher-volume, high-efficiency producers.

Small acreage producers need to identify markets that reward them with higher prices for desired products or product attributes. For example: After completing a budget projection for a potential beef cattle enterprise on a 20-acre pasture, you discover the per acre financial return is far less than desired. This does not necessarily indicate you cannot raise cattle profitably—but it may mean that selling feeder calves at the local sale barn will not generate the desired return. The challenge is then to find ways to “add value” to your cattle production. You might, for example, find it more profitable using the pasture to raise locally-grown freezer beef. That different market channel could allow a higher return per acre for your cattle enterprise.

Direct marketing, selling a product directly to a consumer, can often generate higher returns from smaller acreages. However, there is a high time commitment to market and interact directly with consumers. If your time is limited, or if you are not interested in much customer interaction, you may need to rethink enterprises that depend on direct marketing.

Ask these questions when thinking about marketing:

- Who will buy the product(s)?

- How much are they willing to pay for a product(s)?

- What market channels will effectively reach buyers?

- How much time do you want to spend marketing the product?

- How much do you want to interact with people?

2. Assets

Assets are things with value that you own or can access. Assets also include your knowledge and experiences, and these may be a source of motivation and information when planning for a small acreage enterprise. Your labor availability — both your time and physical ability — is another type of asset.

Consider the following example: A small acreage owner is interested in selling fresh vegetables and flowers at a farmers’ market. She researches equipment and discovers that a compact tractor is commonly used for primary tillage and cultivation. Since she already has a compact tractor to mow her property, she starts to research prices for equipment that could be paired with her tractor for tilling and planting her crops.

Make your asset lists detailed and specific. For example, if you are considering livestock, pasture that has been fenced and maintained for soil fertility is a different starting point than unfenced land that has been occasionally mowed or brush hogged. Certain crops may require specific soil types or characteristics — blueberries prefer a lower soil pH than blackberries, for instance. Some enterprises may be more physically demanding throughout the production cycle than others. These are all examples of how detailed asset lists can help inform the business plan for your small acreage enterprise.

Ask these questions when thinking about the assets you have to begin an enterprise on a small acreage:

Personal: What skills or experience do you bring to a new farm enterprise? What skills do you need to acquire?

Capital: Do you already own land, equipment, buildings or supplies that may be used in a farm enterprise? What is the condition or suitability of those assets? What investment is needed to purchase needed assets? Do you need to secure outside funding? Is there any cost-share or financial assistance available through state or federal sources?

Labor: How much labor will be needed for the enterprise? Will you need to hire outside labor to perform needed activities?

3. Profitability

Profit is the difference between revenue and cost. The profit required from a small acreage enterprise may vary according to operator financial goals. This publication assumes profitability is an important motivation for beginning the small acreage enterprise. Understanding cash flow is a good starting point for understanding financial management and the pathway toward business success and sustainability.

Revenue

Revenue is the product quantity sold times the price received per unit. Determining market demand (how much customers are willing to pay for a certain quantity of product) will help you determine sales revenue.

Be careful not to overestimate the potential revenue from your small acreage enterprise. Conservative revenue projections help create a more achievable profitability projection and can help you avoid the surprise of less revenues than expected.

Expenses

Putting a cost to each input needed for production is also very useful for understanding the materials, activities and labor required to produce goods and services. A detailed production budget forces you to think step-by-step through the production process.

There are different kinds of production costs. Some costs change with the quantity produced: You would need to hire more labor to pick berries from one-half of an acre than one-tenth of an acre. Other costs remain constant no matter how much is produced. Property taxes on 20 acres of pasture are the same regardless how many calves you raise or how much hay you bale from that acreage.

Cash flow activities

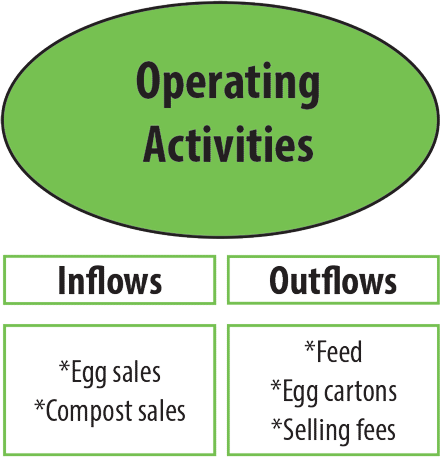

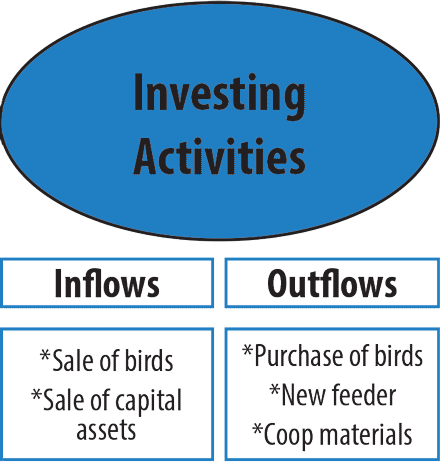

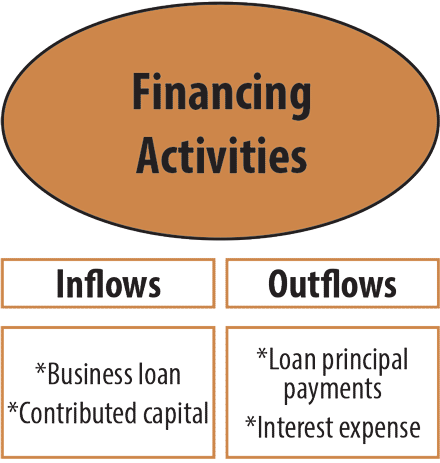

Projecting and estimating cash flows can help you see how cash will be flowing in and out of your enterprise. Figure 4 illustrates three categories of cash flows in a small poultry enterprise: operating, investing and financing activities.

Operating activities are often the main category of cash flows for a small business. In this example, a direct market egg producer receives cash from the operating activities of selling eggs and selling some composted manure. Operating cash outflows in this direct market egg enterprise include buying feed and egg cartons. Outflows could also include marketing costs such as farmers’ market vendor fees, fuel, time spent delivering eggs and cash costs in advertising. It is important not to underestimate marketing costs.

Investing activities are cash flows that come from the purchase or sale of capital assets that are needed to run the business. In this example, capital cash outflows include the purchase of a new feeder and the purchase of materials needed to build a new coop. Capital cash inflows in this example are the occasional sales of pullets and hens, which are not assumed to be a regular source of operating cash income.

Financing activities are cash flows associated with borrowed or the owner’s capital contributions. Loan principal and interest payments are the most common cash outflows in this category. Borrowed funds would be a source of financing cash inflows. Cash from personal funds used for the purchase of business assets is also a source of financing cash inflows.

Sources of loan financing include commercial banks, Farm Credit System institutions, USDA Farm Service Agency and Missouri Agricultural and Small Business Development Authority. It is recommended to visit with financial institutions well in advance to understand if they might be a source of financing the business.

Summary

There are many enterprises possible for small acreage owners and operators in Missouri. Different acreages will be suitable for different enterprises. Be sure to envision your personal or business goals as you consider enterprises that could be feasible on your acreage.

Business planning is an important part of launching a successful small acreage enterprise. The business planning process involves evaluating markets for potential enterprises, identifying assets needed for those enterprises and projecting cash inflows and outflows during the life of the business.

Funding for this publication was provided by the USDA Rural Development Agriculture Innovation Center grant program.