Chapter 8 of the Missouri Master Gardener Core Manual

Pruning is an important practice for maintaining the health, size, form and vigor of trees and shrubs in the landscape. It can reduce transplanting stress by reducing leaf surface area to compensate for root loss during harvest from nursery fields. Pruning of trees is important during the first few seasons after planting to develop a scaffold of strong, well-spaced branches with wide angles of attachment with the trunk. Often the trees that break up in wind and ice storms are those that were never pruned to develop a good structure. Sometimes pruning can be used to slow the spread of decay or disease by removing infected tissues and allowing the plant to seal, or compartmentalize, damage. Pruning can also enhance flowering and fruiting by forcing the growth of new shoots and improving light penetration to lower leaves. Often, plants are pruned simply to keep them in bounds or prevent them from crowding other plants in the landscape. Some gardeners prune plants into interesting and unusual shapes to create interest or make use of a small space.

While there are many possible reasons for pruning, it should not be done indiscriminately. Before the first cut is made, the gardener should think through the objectives for each individual plant and prune accordingly. It is a good practice to make the rounds on a property several times a year to look for developing problems that can be remedied by light pruning. It is always better to do a little pruning yearly than to do major, corrective pruning after years of neglect. Usually when a well-maintained tree grows tall enough that pruning can no longer be done from the ground with a pole saw, there is little need for routine pruning. Occasional removal of dead wood on an old, declining tree is a good practice because it can slow the spread of decay. However, contrary to popular belief, pruning cannot halt or reverse tree decline caused by old age or other stress factors.

When to prune

In general, the best time to prune trees and shrubs is during the dormant season. Major pruning, in which more than 15 percent of the top of a plant is removed, is best left until early spring (February or March). At this time of year, deciduous plants have no foliage so the branching structure can be clearly seen and pruning cuts will callus over quickly. By March, the risk of extremely cold temperatures is minimal, so new growth produced in response to pruning cuts is less vulnerable to freezing injury than it would be after pruning in August or September. Another problem with early fall pruning (before leaf drop) is that minerals in the leaves and stems are removed before they can be moved into stems and roots for winter storage. Similarly, extensive pruning just after a plant has finished a growth flush in spring removes minerals and carbohydrates that have been recently mobilized from the roots and the plant will have less foliage to produce carbohydrates to replenish the food reserves of the roots.

Minor pruning (less than 10 percent of the plant removed) can be done at any time of the year. Never be afraid to remove an errant branch growing toward the sidewalk or to eliminate a branch that competes with the main shoot (leader) or forms a narrow branch angle. Evergreen and newly planted deciduous shrubs often benefit from pruning of tips several times during the growing season to increase branching.

For some plants, the time of flowering determines the best time to prune. Pruning a plant that blooms in March or April during the dormant season will remove flower buds and may lead to a poor bloom display. Pruning just after bloom will allow enjoyment of the flowers and provide plenty of time for flower buds to form for the next spring’s bloom. However, plants that bloom in the summer or fall on “current season’s” growth can be pruned hard in February or March and still bloom well. In many cases, cutting back summer-flowering plants in spring actually enhances the bloom display.

Pruning tools

Using the proper tools for pruning makes the work easier and prevents unnecessary damage to the plants being pruned. There is a confusing array of pruning tools available, but the choice of tools is simplified by keeping a few principles in mind. First, the pruning implement should make a cut with smooth edges and should not crush the stem that remains after the cut. Second, the tool should cut efficiently and should not require undue effort on the part of the pruner. Third, the tool should be durable, with cutting edges that can be resharpened or replaced when worn out. Inexpensive tools fail at least one of these selection criteria. Purchasing a high-quality pruning tool is a good investment if one intends to do a significant amount of pruning.

A good pair of hand shears is a must for the serious gardener. The two basic types of hand shears are anvil and bypass pruners. Anvil pruners cut by squeezing the stem between a flat surface and a sharpened blade. In some cases, especially when the blade is dull, this action can result in stem damage from crushing. Bypass pruners cut with a slicing action, like scissors, and generally make a more precise cut than anvil pruners. For branches larger than about 1/2 inch in diameter, lopping shears are required. These are similar in design to hand shears but have long handles and a sturdier build. When purchasing lopping shears, consider the maximum diameter of cut that you are likely to make and buy a tool that is sturdy enough to do the job but not so heavy that it will cause fatigue before the work is done.

Cutting branches larger than 1-1/2 inches in diameter is best done with a saw. Pruning saws differ from those used by carpenters in that the teeth slant toward the handle so that cutting occurs on the pull stroke. Often the blades are curved and narrower at the tip than at the base. These features allow the saw to be used in tight spaces and make it easier to control the cut. A blade with seven to eight teeth per inch will cut tree and shrub branches efficiently with a fairly smooth edge to the cut.

As the landscape begins to mature, a pole pruner may be a good investment. This tool usually has a saw attached to the end of a 10- to 20-foot extendable pole and allows the user to correct developing problems without the use of a ladder. Pruning from a ladder with hand shears, loppers or saws is dangerous. Pole pruners often are fitted with bypass shears that can be operated by a pull cord to make small cuts. This is useful for removing or heading back branches that show potential to compete with the central leader for apical dominance.

Since pruning tools can be expensive, they should be given routine maintenance. Clean sap and resin from the blades with alcohol and sharpen the blades as needed. Always dry the tool before storing to prevent rust, and oil the moving parts to prevent binding. Keep in mind that improper sharpening can quickly make a tool useless. For example, the blade on a bypass pruner is beveled on one side only. Beveling the flat side will make the tool nonfunctional. If one does not know the proper way to sharpen a tool, it is best to use a sharpening service that specializes in knives, scissors and saws. Also, avoid the temptation to use a tool on branches larger than it is designed to cut. This can spring the blade and make the tool ineffective.

Anvil type hand shears and scissors type hand shears.

Anvil type hand shears and scissors type hand shears.

Lopping shears.

Lopping shears.

Pruning saw.

Pruning saw.

Hedge shears.

Hedge shears.

General pruning approach

A gardener should always have objectives in mind when pruning an individual plant. First, visualize the natural form of the plant to be pruned, based on references and personal experience. It can be frustrating to try to force a plant with a naturally multistemmed habit to grow in a tree form. With the natural form in mind, envision the types of cuts that might be made to encourage the plant to grow in an aesthetically pleasing way into the space provided for it. This may involve thinning out crowded branches and cutting back long shoots that are out of bounds. Sometimes the best approach will be to cut some or all of the shoots back to near the ground to force new, vigorous growth.

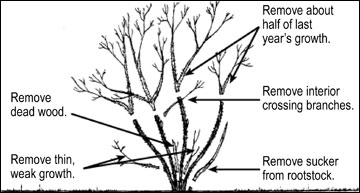

Once the general approach has been decided, it is helpful to go through a mental checklist to make pruning decisions a little easier. Walk around the plant to view it from all sides. First, remove unwanted sprouts (suckers) growing from the base of the plant. In general, rank-growing, vertical shoots (sometimes called water sprouts) arising from the ground or from horizontal branches serve no good purpose. These should be removed or cut back to lateral buds or branches. Next, look for branches that are broken, crossing or rubbing each other and correct these problems. Finally, remove branches that are growing inward, toward the center of the plant. Once these steps have been taken, little if any additional pruning may be necessary. Keep in mind that excessive pruning can lead to unmanageable growth.

Types of pruning cuts

The two main types of cuts made during a pruning operation are thinning cuts and heading cuts. In most cases, both thinning and heading are used to encourage reasonably vigorous growth in the right directions. Thinning cuts remove entire branches back to the trunk, to main branches or to the ground. This opens a plant up to allow better light penetration and air circulation, while maintaining the overall form. Heading cuts remove branch tips back to lateral buds or small side branches. Generally, two to four new branches arise from the buds or branches just below the heading cut, increasing branch density (Figure 1). Often, when thinning cuts are made, the remaining branches will respond by growing long and leggy. Heading some branches after thinning will often reduce this legginess. Also, when some upper branches show the potential to compete with the terminal leader for dominance, heading them back will encourage the development of a strong leader.

Figure 1

Figure 1

By midsummer, four branches have developed on this crabapple shoot just below a heading cut made in March.

Making the proper cuts

When removing or heading back a branch, the cut should be as smooth as possible and no stub should be left. When heading, cut back to about 1/4 inch above a healthy bud facing away from the center of the plant. Cutting too close to the bud may cause it to dry out and die. A stub longer than 1/2 inch left above a bud will usually die and decay. When cutting back to a side branch, try to select a branch that is at least half the diameter of the main branch and is attached at an angle of less than 45 degrees to the branch being cut. Cut with a smooth motion and do not twist the shears.

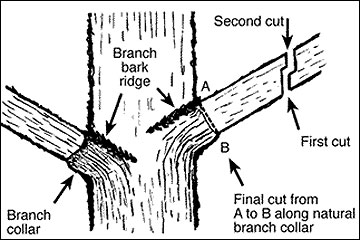

When it is necessary to remove a branch larger than 2 inches in diameter with a pruning saw, it is important to avoid stripping bark below the point of branch attachment with the trunk. This can be achieved by using the three-cut removal method. The first cut is made a few inches away from the trunk, partially through the branch, from the underside. The second cut is made through the branch, a few inches farther away from the trunk, starting from the upper side. This removes the weight of the branch, allowing the third cut to remove the stub with no danger of bark stripping. Research has shown that branches cut “flush” with the trunk take longer to cover and compartmentalize pruning wounds than those cut at an angle to preserve the “branch collar” as shown in Figure 2. Tree experts generally agree that pruning paints have no beneficial effect and in some cases can actually interfere with natural wound covering and compartmentalization by the tree.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Pruning at the branch collar encourages formation of a callus that seals the wound and protects the tree.

Pruning for specific plant types and situations

Shade trees

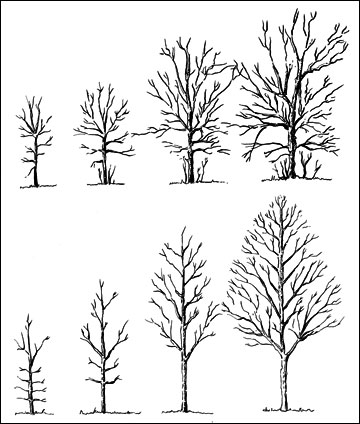

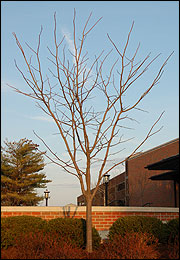

It is important to prune newly planted trees annually for the first few years to develop a branch structure that will withstand wind and ice storms as the tree matures (Figure 3). Keep in mind, however, that different species have differing natural forms (see box). Some species, such as bald cypress, have an “excurrent” growth habit, retaining a strong central leader even at maturity (Figure 4). Other trees have a “decurrent” habit, in which a number of main branches develop, leading to a more spreading form (Figure 5). When pruning a new tree, try to envision its ideal structure in 20 years and remove branches that detract from that structure. In general, decurrent species require more attention, since they have a tendency to develop “codominant” or competing leaders (Figure 6). Often these species have an opposite bud arrangement, and maintaining a central leader may require removing one of the paired buds at the tip of the leader each year.

Training a new tree should be done over a period of years. Do not remove lower branches higher than one-third of a tree’s height. It may take several years before the lowermost main branch can be established. If, for example, 7 feet of clearance is required for a tree near a sidewalk, the tree may be 20 feet tall before the lowermost scaffold branch can be selected. The ideal scaffold branch spacing and distribution will depend somewhat on the ultimate size of the tree. The vertical distance between branches should be about 5 percent of the ultimate height of a tree. So for a 40-foot tree, there should be about 2 feet between branches. Branches should be arranged spirally, so that no branch is directly above another (Figure 7). So, if there are six main branches spiraling up a tree, each one might make about a 105-degree angle with the one below it, when viewed from the underside. Try to select scaffold branches that form an angle of at least 40 degrees with the main trunk. Upright-growing branches with narrow angles of attachment to the trunk tend to be structurally weak.

In some cases, it may not be necessary to remove an entire branch. Heading can be used to keep a branch small in relation to other branches, encouraging other branches to develop in the desired directions. This may be preferable to removing a branch on a neglected tree when doing so would violate the 25 percent rule of thumb.

Unfortunately, trees are often planted in places where they do not have room to reach their mature heights. Sometimes, such as when trees interfere with power lines, removal is the best option. It may, however, be possible to reduce the height of a tree while maintaining its health and visual appeal. Topping, a common approach in which tops of trees are cut indiscriminately to stubs, has many negative effects on tree health and appearance. This approach starves the roots of carbohydrates and causes proliferation of many poorly attached shoots that break off during storms. A better approach is to cut back some of the tallest branches to the points where they attach with large-diameter secondary branches. This approach can reduce the height of a tree significantly without weakening it and ruining its visual appeal

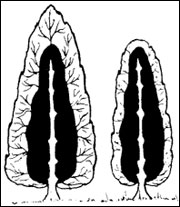

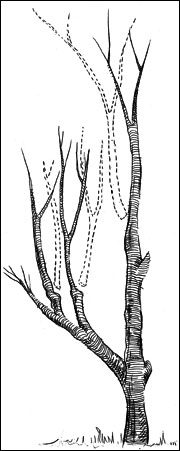

Figure 3

Figure 3

Newly planted trees should be pruned annually for the first few years. A tree pruned annually (bottom) will have a more pleasing shape and be more resistant to storm damage than a similar tree that is not pruned (top).

Remove basal suckers, poorly placed branches, and branches with narrow angles with the trunk. Remove lower ranches gradually, never limbing up more than one-third of the way up the trunk in any given year.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Species with an excurrent growth habit, such as bald cypress (left) and littleleaf linden (right) have a strong central stem, or leader.

Figure 5

Figure 5

The decurrent branching habit — development of many main branches of equal size — gives Shantung maple (shown here) its spreading form.

Figure 6

Figure 6

Decurrent-branching species such as yellowwood (shown here) tend to develop “codominant” or competing leaders.

Figure 7

Figure 7

Scaffold branches should have good vertical as well as radial spacing.

Narrow-leaved (coniferous) evergreens, shrubs

Junipers and yews are the most commonly planted of the narrow-leaved evergreens. Although some dwarf forms are available, most cultivars require some annual pruning to control size, shape and density. More compact plants result when long branches are pruned back to their junction at a lateral branch during early spring. Cuts should be made “back in” so that new growth will soon cover exposed stubs (see Figure 8).

Green foliage must remain on any branches of junipers that are cut back. They seldom are able to develop new growth from bare stubs. Yews can be cut back more severely and are often able to survive a 50 percent size reduction. Vigorously growing yews may need a second light pruning later in the summer to remove long shoots that have developed. Severe pruning to either of these types of plants should be done in April, although light pruning may be done at any time of year.

Arborvitae, as well as juniper, develops a dead zone in the center of the plant. When pruning is done either on the tip or the sides, cuts should not be made into the dead zone. Any severe pruning of these plants should be done in March or April. Overgrown arborvitae cannot be pruned back more than 20 percent. Pyramidal junipers may be reduced in height by about 20 percent (see Figure 9) but should not be cut into the dead zone. A new leader cannot develop on plants that have been cut back too far.

Mugho pines may be pruned in the spring when the new shoots, which look like candles, develop. When the “candle” has extended almost to its full length, but before the needles are fully developed, remove about half the length of the “candle” (see Figure 10). This will promote compactness of the plant. This method may be used on other pines as well.

For many years, shearing evergreen shrubs has been popular. However, sheared plants produce a formality not suitable for modern, natural landscapes. The shearing process often aids in spreading disease and other plant problems. Once a plant has been sheared, it is almost impossible to restore its natural form. It is, therefore, best to reserve shearing for hedge plants.

Figure 8

Figure 8

Prune evergreen shrubs so that new growth covers stubs.

Figure 9

Figure 9

Pyramidal junipers may be shortened by 20 percent, but do not cut into the dead zone (at left shown in black).

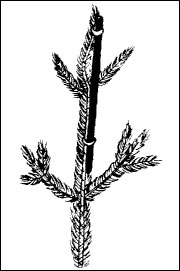

Figure 10

Figure 10

Trim mugho pine “candles” by half to promote compactness.

Narrow-leaved (coniferous) evergreens, evergreen trees

The narrow-leaved evergreen trees in Missouri are mainly pines and spruce. Fir, hemlock and Douglas fir are also sometimes planted. All the tree forms of these plants grow quite large under good conditions. If planted where they have adequate space for growth, they are seldom pruned. When pruning is necessary, it is done in early summer with the removal of half of the terminal candle (see Figure 11). For extra bushiness, terminals of lateral branches may be removed as shown.

Terminal buds of evergreen trees are easily damaged. If more than one shoot develops from a damaged tip, only the strongest shoot should be left to develop into a new terminal. When the entire terminal dies or is removed, a new leader can be developed by tying up a lateral branch where the original terminal had been (see Figure 12).

New growth on lateral (side) branches may be cut slightly shorter than that on the leader. Evergreen trees will not recover well if cut back severely.

Where severe pruning is necessary, spruce will recover from cuts back as far as two-year-old wood. Firs can be cut back as far as three- or four-year-old wood. However, if sited correctly, pines, spruce, fir and hemlock trees should require little or no pruning.

Figure 11

Figure 11

Prune evergreen trees by removing half of new growth.

Figure 12

Figure 12

Training a new leader.

Broad-leaved evergreens

In Missouri, most broad-leaved evergreens do not grow rapidly and generally require little pruning. Any dead or diseased parts should be removed promptly. Rhododendrons may occasionally need some light pruning. It is important to remove flower stems as soon as flowering is finished (see Figure 13). Carefully cut or pinch out the flower head, leaving the small developing buds at the base of the flower (Figure 14). Failure to do this promptly can reduce flowering the following year (Figure 15).

Both azaleas and rhododendrons should be pruned after flowering. Never cut into areas of bare stems or sparse foliage. These shrubs will sprout poorly or not at all. When a fairly severe pruning is required, no more than one-third of the branches should be cut back in a single season. In three years, the pruning will be complete.

Mahonia and similar plants may develop old shoots with bare stems. These may be removed at ground level and the stumps will produce new growth. American holly will stand heavy pruning. Most people prefer to prune at Christmas time when the branches can be used indoors. Japanese hollies seldom require much pruning in Missouri.

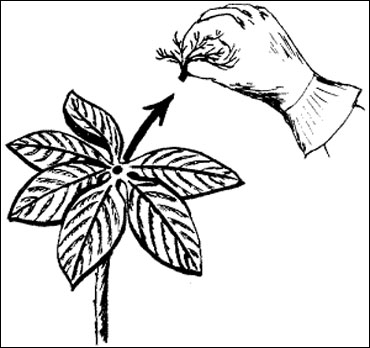

Figure 13

Figure 13

Remove rhododendron flower stems as soon as flowering ends.

Figure 14

Figure 14

Shoots develop from buds just below where the flower cluster was pruned off after bloom. These shoots will produce new flower buds by the end of the season.

Figure 15

Figure 15

Removal of flower heads after blooming promotes better flowering in the next season.

Deciduous shrubs

The majority of plants used in Missouri landscapes are deciduous. Deciduous shrubs are generally divided into two groups — species that produce their flowers early in the spring and those that bloom in summer or fall. Spring-flowering shrubs include such popular plants as forsythia, deutzia, lilac, viburnum, mock-orange and spirea. Flowers are produced on these shrubs from buds formed the previous summer or fall. If these shrubs are pruned before they bloom, many of the flower buds will be removed, reducing the flowering display for that season. To ensure maximum flowering, these shrubs should be pruned as soon as possible after blooming is completed. Wounds heal quickly at that time and dead wood can be easily seen.

For easiest pruning, first, with pruning shears remove all weak growth and dead, diseased, split or crossed branches. The form and shape of the shrub can be most easily maintained by starting at the top of the shrub and working down. Next, use the loppers or a pruning saw to remove as many of the oldest canes as necessary at ground level. The previous pruning was necessary to determine which branches could be removed without appreciably changing the overall form or shape of the shrub. One-third to one-fourth of the stems should be removed annually so that the shrub is completely renewed every three to four years. This technique promotes vigorous growth, which forms strong flower buds. Plants such as pyracantha and Japanese quince produce flowers and berries on branches more than one year old. For this reason, these plants should never be pruned excessively at one time (Figure 16).

Summer- and fall-blooming shrubs include such plants as abelia, beautyberry, butterfly bush, rose of Sharon, crapemyrtle and summersweet. Most of these plants flower on wood that is produced during the current growing season. These plants should be pruned at any time before new growth begins in spring. The method of pruning is similar to that described for spring-flowering shrubs. A few, such as butterfly bush and beautyberry, are often cut back completely to the ground level in spring. In northern Missouri, crapemyrtles often die back during the winter. They should be pruned back to the highest point where green shoots are arising after growth is evident in April or May.

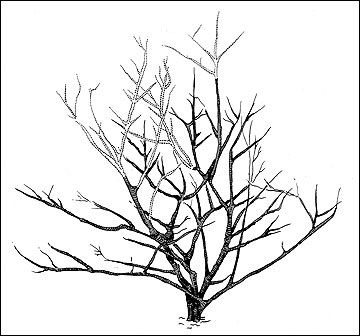

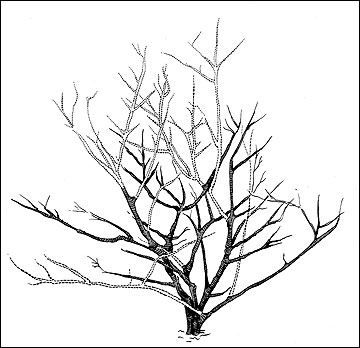

Figure 16

Figure 16

When pruning a large deciduous, flowering shrub such as this ‘Sarcoxie’ viburnum, the objectives should be to improve light penetration to the center of the plant, to keep the plant within its bounds and to preserve its natural form. This usually involves both heading and thinning cuts (dashed lines indicate pruned branches).

A. Start at the top by reducing the lengths of outlying branches, cutting back to laterals or strong, outward-facing buds.

B. Then cut a few of the crowded, interior branches back to the main branches.

B. Then cut a few of the crowded, interior branches back to the main branches.

C. The finished product will have a pleasing shape and will produce a showier bloom display than if it had been left unpruned.

C. The finished product will have a pleasing shape and will produce a showier bloom display than if it had been left unpruned.

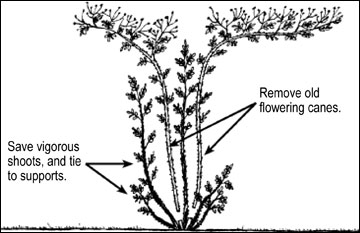

Roses

Roses

Popular roses such as the hybrid teas, floribundas, grandifloras, hybrid perpetuals and polyanthas should be pruned in early spring as the buds are swelling but before growth has started. Remove all dead wood by cutting at least an inch below the dead area. In some cases, entire canes may be winterkilled and should be removed. Vigorous plants that have not been killed back should be pruned to between 18 and 24 inches. Remove all weak, thin wood at the base and select three to five strong canes (Figure 17). Vigorous canes should be cut to a large, strong bud preferably facing outward.

Shrub roses that flower only in spring should be pruned after they have flowered. Generally, this consists of removing old canes, dead wood and dead flowers. They should be allowed to develop in their natural shape.

Fall pruning of hybrid tea roses should consist of removing some of the top, brushy growth. This will reduce the tendency for the bush to be torn loose during the winter by high or persistent winds.

Climbing roses may require two types of pruning. Those climbing roses that are derived from hybrid tea varieties such as climbing Peace or climbing Crimson Glory should not be pruned heavily, and only dead wood, weak wood and bloomed-out flower stems should be removed back to a vigorous bud (Figure 18). Occasionally, old canes may be removed. The vigorous climbers known as ramblers that flower in the spring only may be pruned after flowering. Remove old, woody canes that have finished flowering at ground level (Figure 19). Allow new canes to remain and head back those that become too large. New canes trained in a somewhat horizontal position generally flower more heavily than those allowed to grow in a vertical position.

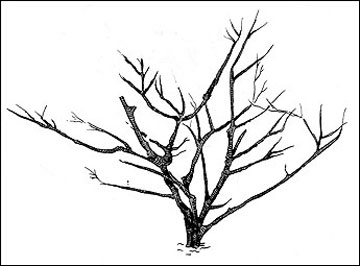

Figure 17

Figure 17

Pruning hybrid teas, floribunda, or grandiflora roses.

Figure 18

Figure 18

Prune repeat blooming climbers while dormant.

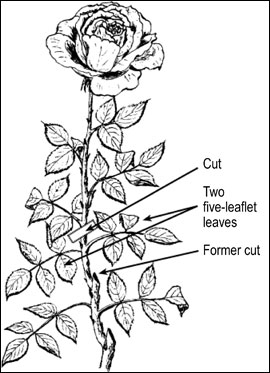

Figure 19

Figure 19

Prune vigorous climbers and ramblers after flowering.

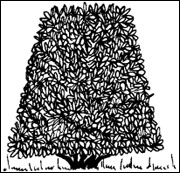

Hedges

A hedge must be pruned regularly to remain attractive. Most hedges need trimming at least twice a year, but some need as many as three and four trimmings a year. A dense hedge must be developed slowly. Never try to make a hedge reach the desired height in a single season or it will be thin and open at the base. Plants such as privet or barberry need severe pruning immediately after planting and at the beginning of the second year to make them bushy. To develop a hedge that is well filled at the base, always trim so that the base is wider than the top (see Figure 20). If the top is allowed to become wider than the base, the base will become thin and open as lower branches are shaded out (Figure 21).

Figure 20

Figure 20

Maintain hedges wider at the base than at the top.

Figure 21

Figure 21

Hedges allowed to become wider at the top become thin and open.

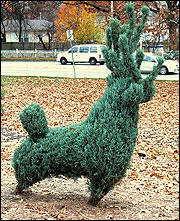

Unusual forms

In some situations, it may be necessary or desirable to prune trees or shrubs into unusual forms to meet landscape needs. Certain plants like boxwoods, Sargent juniper and hornbeams are easily pruned into interesting shapes (Figure 22). This method of pruning can add flair to the landscape but requires considerable time and labor to maintain.

Espalier is a form of pruning in which a plant is trained to grow in one plane (Figure 23). This technique is sometimes used to grow fruit in a landscape where space is limited. It is also useful, however, to create interest in the garden by contrasting flowering trees and shrubs against a wall. Plants like crabapple, flowering quince and some magnolias lend themselves to this method. Plants are usually pruned so that branches can be attached to trellis wires along a fence or next to a wall. Another advantage of this approach is that it can allow marginally hardy plants to be grown in a protected microclimate.

Figure 22

Figure 22

Boxwoods, Sargent juniper and hornbeams are easily pruned into interesting shapes.

Figure 23

Figure 23

Espalier pruning can be used to train plants to grow along a fence or next to a wall.

Original author

Christopher J. Starbuck

David Trinklein

David Trinklein