Maintaining and replacing fences is an essential part of land and livestock ownership. In most situations, sound relationships with neighbors and a desire to be civil and cooperative make division fences a nonissue. However, disputes can arise when there are differences of opinion on repairing or replacing division fences. Clear cut rules for handling these situations are needed to resolve conflict and settle disputes.

Missouri Revised Statutes (RSMo) Chapter 272 contains legal guidance for most situations regarding division fences. RSMo refers to the fence separating two adjoining properties as a division fence. Although many farmers and landowners may consider this fence a boundary fence and refer to a division fence as one separating fields, pastures or paddocks owned by the same person, this guide will use the definition of a division fence as established by RSMo 272.

Types of fence laws in Missouri

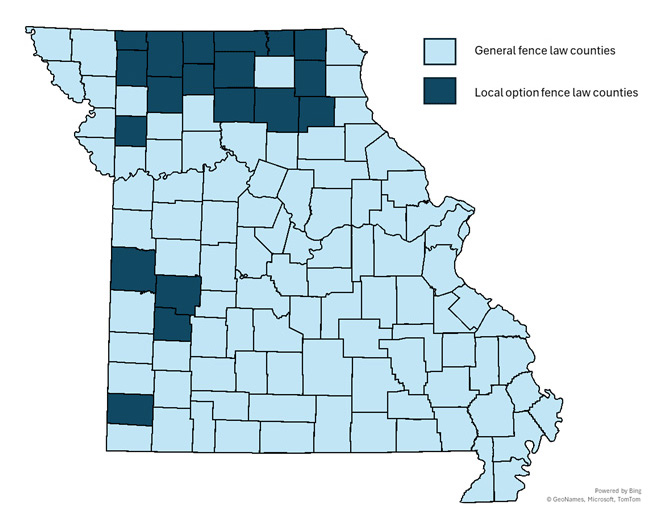

Missouri counties have the option to choose between general fence law and local option fence law, which are differentiated in this guide. General fence law is the default across the state. A county can adopt local option fence law by a vote of its citizenry. The local option is covered by a different set of statutes that are generally more favorable to livestock owners. It is crucial to know your county’s designation when an event occurs causing you to reference Missouri’s fence law.

The map in Figure 1 indicates which fence law is in effect by county. Currently, the following 20 counties are subject to the local option fence law: Bates, Caldwell, Cedar, Clinton, Daviess, Gentry, Grundy, Harrison, Knox, Linn, Macon, Mercer, Newton, Putnam, St. Clair, Schuyler, Scotland, Shelby, Sullivan, and Worth.

Division fence responsibilities

Division fences can cause disputes between neighbors when responsibilities for maintenance and costs are unclear. Missouri’s laws assign legal responsibilities for the fence differently depending on the type of fence law in effect.

General fence law counties

- A landowner without livestock is not required to contribute to the cost of constructing or maintaining a division fence. If the landowner not contributing to a fence places livestock against it later, he or she must reimburse the livestock-owning neighbor for half of the fence costs (272.132).

- If both landowners have livestock and agree to contribute to a fence, each must maintain their portion as determined by the parties facing each other across the fence at its midpoint and each taking responsibility for the half extending to their right from the midpoint to the end of the division fence (272.060). This method ensures fairness in most scenarios and provides clarity for maintenance responsibilities.

- Other arrangements for responsibility for a fence are permitted. To formalize an alternative agreement, record the arrangements in writing and submit to the county recorder of deeds. The arrangements will then be passed to the future owners of both properties when the deed is transferred.

- Either landowner may repair a division fence in its entirety after notifying the neighbor in writing and the neighbor failing to take action to maintain the fence to the minimum standard within a reasonable time. The landowner performing the work is entitled to compensation for half the work done (272.080). Adjoining landowners are also permitted to cross the fence for the purpose of repairing it (272.110).

Local option fence law counties

- Both landowners are required to share equally in the cost and maintenance of a division fence, even if one party does not own livestock (272.235).

- If one landowner wishes to repair or replace the neighbor’s portion of the fence, he or she may notify the neighbor in writing of the request. If no action is taken within 90 days, the landowner may then be authorized to complete the work by a circuit judge. The judge has the authority to order reimbursement for the work done (272.240).

Legal definition of a lawful fence

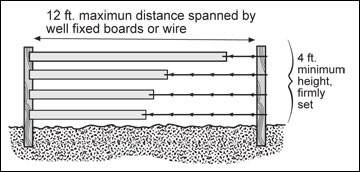

Missouri law provides a specific definition for what constitutes a lawful fence. According to RSMo Section 272.020, a lawful fence under general fence law (Figure 2) must meet these criteria:

- Be at least 4 feet high

- Consist of posts no more than 12 feet apart and securely fastened horizontal boards or wires

- Be sturdy enough to contain large livestock

- Be mutually agreed upon by both adjoining landowners

- Be maintained to a standard meeting the above characteristics

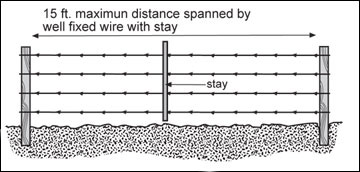

A lawful fence under local option fence law (RSMo Section 272.210) (Figure 3) must meet these criteria:

- Have at least four barbed wires or boards per 4 feet of height

- Have a substantial post placed every 12 feet, or every 15 feet if a vertical stay is used in between posts

- Be otherwise configured but meet or exceed the requirements above

- Be maintained to a standard meeting the above characteristics

Resolving fence disputes

Maintaining good relationships and open communication with neighbors is the best way to handle fence and property line disagreements. Even so, disputes over division fences are common and can lead to significant tension between neighbors. The first strategy to limit future disputes is to place all current agreements in writing. If conflict does arise, Missouri law provides mechanisms to resolve it. The mechanism in place is largely the same between the local option and general fence laws. The mechanisms for conflict resolution are described in RSMo Chapter 272, Sections 040, 070, 090, 100, 120, 240, 250, 260, 280, 300, 340 and 350. The procedures for various dispute resolutions are summarized below.

- Appear before the circuit court judge in the county where the dispute occurred.

- When one party refuses to pay for or perform repairs to a division fence, the judge can order payment to the party taking full responsibility for the fence.

- When the fence itself has some bearing on the ultimate decision — including but not limited to deciding which half of the fence is to be maintained by one party, where the center point of the fence is, what the value of a lawful fence is, and assessment of a lawful fence — the circuit judge may appoint three individuals from disinterested households in the township to look at the fence and make recommendations about the disagreement to the judge. The judge should then use this recommendation to remedy the situation monetarily or materially.

Livestock owner liability

Livestock owners must take reasonable steps to prevent their animals from escaping. Under Missouri law, livestock owners may be held liable for damages caused by their animals if they were negligent in maintaining adequate fencing. This principle is outlined in RSMo Section 272.030. Additionally, RSMo Section 272.050 states that if a neighbor’s livestock escape onto your property as a result of your own negligence in maintaining your portion of the division fence and you injure or kill said livestock, the owner may be due double the amount of the damages as a result of the loss of livestock and your negligence to maintain the division fence.

Local option fence law does not specifically address liability for livestock or negligence. In these counties, questions of escaped livestock defer to RSMo Chapter 270. Under this law, livestock owners may be required to pay other individuals or authorities for damage caused by livestock or for the care of livestock until it is returned to its enclosure. Additionally, Section 270.060 states that no person should have the obligation to fence livestock out of their property, inversely implying that livestock owners are responsible for always keeping their animals in an enclosure.

Other types of division fences

If a public road or right-of-way dissects your property or serves as the boundary between a neighboring property, two separate division fences may be required. An easement grants a third party the right to use a portion of your land for a specific purpose, such as accessing utilities or a roadway. In a scenario where the easement must have unobstructed access to a public road and runs directly on or near the property line, both neighbors may be required to own and maintain their own division fence. In this case, each landowner will have sole responsibility for the entire fence on their side. Boundaries following bodies of water are expected to be treated in the same manner if a landowner requires a fence to exclude the body of water. Many easements will have specified setbacks for fences, if necessary. Some county roads do not have deeded easements. If a county roadway is not deeded, RSMo Section 229.010 states that all public roads are 30 feet wide, so fences should be set at least 15 feet from the centerline of the road.

If a fence borders a railroad, then the railroad owns and maintains the entire fence. If the railroad is negligent in maintaining the fence, they may be liable for damages to escaped livestock.

Boundary line disputes

Boundary location disputes usually arise when old fences are being rebuilt or relocated. The legal doctrine of adverse possession, often referred to as squatter’s rights, states that someone in possession of land continuously for a period of 10 years may receive absolute title to the land if his or her possession was adverse to the interests of the true owner. A court and jury will decide based on the facts of the individual case.

A quiet title lawsuit — so called because it quiets any challenges or claims to a title — may decide whether all five elements of adverse possession are present in any given factual situation. Title may be established for the adverse possessor, the claimant, if the possession meets these conditions continuously for a period of 10 or more years:

- The land is physically occupied by the claimant.

- The claimant has had exclusive use of the property for 10 or more years.

- The claimant’s use and occupation has been continuous and uninterrupted.

- The claimant openly occupies the property without any effort to conceal the occupation.

- The occupation is hostile, meaning that the deeded owner has not given permission of any kind to the claimant to occupy the property for any reason.

Tenants cannot assert adverse possession even after leasing the property for more than 10 years because they are there with the consent of the landowner.

If a title is acquired by adverse possession, it cannot be made “marketable of record” until either a court has rendered judgment that all the requirements of the doctrine of adverse possession have been met, or the neighboring landowners have given each other signed, notarized and recorded quitclaim deeds. The “quitclaim approach” is a settlement out-of-court and should be done with legal advice.

Most recent updates

Missouri fence law was most recently updated in 2016 with these changes:

Section 272.030 — Revised to remove outdated provisions for the care of escaped livestock and more directly address the liability for damage done by escaped animals. The new statute says, “If any livestock break through a lawful fence … and by doing so obtain access to or trespass upon another’s property, the owner of the animal is liable for damages if he or she was negligent (in maintaining a lawful fence).” The previous version of the statute said: “If any horses, cattle or other stock shall break over or through any lawful fence, as defined in section 272.020, and by so doing obtain access to, or do trespass upon, the premises of another, the owner of such animal shall, for the first trespass, make reparation to the party injured for the true value of the damages sustained, to be recovered with costs before a circuit or associate circuit judge, and for any subsequent trespass the party injured may put up said animal or animals and take good care of the same and immediately notify the owner, who shall pay to taker-up the amount of the damages sustained, and such compensation as shall be reasonable for the taking up and keeping of such animals, before he shall be allowed to remove the same, and if the owner and taker-up cannot agree upon the amount of the damages and compensation, either party may institute an action in circuit court as in other civil cases. If the owner recover, he shall recover his costs and any damages he may have sustained, and the court shall issue an order requiring the taker-up to deliver to him the animals. If the taker-up recover, the judgment shall be a lien upon the animals taken up, and in addition to a general judgment and execution, he shall have a special execution against such animals to pay the judgment rendered, and costs.”

Section 272.230 — Repealed. This statute was nearly identical to the version of 272.030 that was replaced (see above). However, no new statute was provided for local option fence law.

Resources

- Visit the Missouri Bar website for a list of Missouri lawyers who currently accept new clients.

- Missouri Revised Statutes on fence law. The general law is in sections 272.010 to 272.136; the local option law is in sections 272.210 to 272.370.

The authors are grateful for the legal review of this publication provided by Brent Haden, founder and partner at The Law Firm of Haden & Colbert.