American black bears (Ursus americanus) are the most abundant bear species in North America, and populations have been gradually increasing in Missouri over the past several years. As of 2025, it is estimated that 1,000 bears currently reside in the state. Black bears (Figure 1) are native to Missouri and were abundant throughout the state until the 19th century, when bear populations decreased due to unregulated harvests and losses of forest habitat.

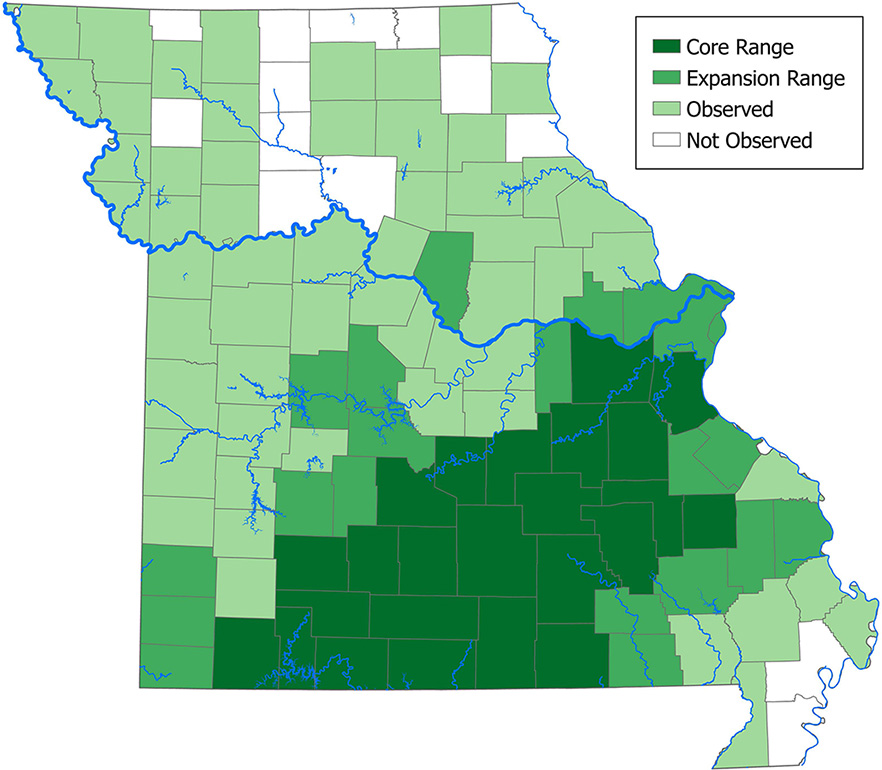

During the 1960s, the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission captured 254 black bears in Minnesota and Manitoba, Canada, and released them in the Ozark and Ouachita mountain ranges in northern and western Arkansas. Over time, Arkansas’ bear population increased, and as a result, hunting seasons were established. Over the past several decades, bear numbers have been gradually increasing in Missouri as bears from Arkansas have been dispersing northward into available habitats in the Ozark region and mixing with Missouri’s remnant population. More recently, bears have been observed regularly north of the Missouri River, which further suggests that black bear populations are expanding their range in Missouri. The growth of Missouri’s bear population should be considered a significant conservation success story. Now that a sustainable population is in place, a highly regulated hunting season has been established in certain areas of the state.

Ecology of black bears in Missouri

In Missouri, adult male black bears typically range from 130 to 600 pounds and average 280 pounds; adult females range from 90 to 296 pounds and average 179 pounds. Their weights vary considerably within and between years, depending on food abundance.

Black bears are known for their black coats, brown colored muzzles, rounded ears, short sharp claws and, on occasion, white chest markings. However, in Missouri, black bears can range in color from black to brown, to reddish brown, or cinnamon, to blond. Traditionally, Missouri’s black bears were black in color, but after the introduction of bears from Minnesota and Canada into Arkansas, genes for additional coat colors have become more common. Black bear claws are built for climbing, and bears use them to climb trees to escape from danger or to forage on hard and soft mast in treetops. They can also use their claws for digging and for ripping open logs when searching for food. Bears typically walk on all four feet but will stand upright when foraging or trying to better observe unknown objects. Figure 2 depicts their tracks, which show their claws and pads.

Bears have good eyesight and strong hearing, and their sense of smell is especially well developed — they can detect food resources at great distances. Excellent swimmers, black bears can easily swim across small lakes and rivers. They are rarely vocal but do have several distinctive calls, including growls, whining and other warning sounds.

Because bears tend to live solitary lives, it is very difficult to distinguish males from females unless bears are with their cubs, as cubs accompany the female and not the male bear. Males are often larger than females, but unless they are observed together, there is a good chance of error in determining the sex. Yet, a trained eye can observe that adult males have larger, squared heads as compared with the females’ rounder, elongated heads. In addition, large males have stockier legs that are even in width between their ankle and paw, whereas the females’ legs are thinner and ankles are narrower than their paws.

Aging bears in the field can be difficult, but an experienced observer might be able to tell if a bear is an adult or subadult (1½ to 3½ years of age) based on the body size and shape. Usually, healthy adults appear to have stubbier legs and shorter rounded ears compared to subadults, as adults have larger fat and muscle stores that fill out their frames more. In the spring and summer, cubs are easy to identify when compared to their mothers because the cubs are much smaller then, but they can be similar in size in the fall.

A more accurate way to age a bear is by its teeth. Bear teeth wear down somewhat consistently over time, and through examining the wear on a bear’s molars and incisors, one might be able to age a bear within a few years. However, the most accurate way to age a bear is by counting the growth rings, called cementum annuli, on a tooth. This technique involves extracting a single tooth, usually a lower premolar; cutting a thin cross-section of the tooth; staining it to highlight the growth layers; and viewing it on a microscopic slide. In the wild, bears in populations that are hunted seldom live longer than 20 years.

Hibernation and denning

Hibernation is a behavioral trait that is essential for bears to survive in locations where there may be a scarcity of food, deep snow accumulations and long periods of cold weather. With adequate fat reserves, bears can fast for six months. During hibernation, they experience only a slight reduction in body temperature and are able to depress their heart rate and lower their breathing frequency. Decreased day length and inclement weather in the fall can influence the onset of hibernation. In addition, the availability of food can influence how long a bear will hibernate. If food is limited and winter temperatures are low, bears will likely stay in their dens for most of the winter. If winter temperatures rarely fall below freezing and food is still available, some bears might hibernate for only a short time. However, no matter the winter weather conditions, females expecting to give birth will reside in a den to provide a stable area for cubs to grow until they are mobile and to provide shelter from potential danger.

Biologists sometimes use the term “hibernation” to describe the period of denning and inactivity for bears; however, a bear’s body temperature does not drop as low as that of other animals that hibernate during the winter, such as woodchucks and chipmunks, but is only slightly lowered (8 to 12 degrees F below regular body temperature). Conversely, a bear’s heart rate is greatly reduced, dropping from 40 to 50 beats per minute to 8 to 12 beats per minute. Oxygen consumption drops by 50% or more. In addition, unlike many small mammal hibernators, bears do not have to eat or eliminate wastes during hibernation but subsist entirely on fat reserves. Bears develop a fecal plug to seal off their digestive tract. Some hibernation researchers consider bears to have adaptations that are superior to other hibernators, such as in the areas of nitrogen and bone metabolism. Bears are apparently unique in the animal kingdom in their ability to prevent toxic products from protein digestion from accumulating in their blood. Bears have unique biochemical pathways that rebuild protein, not allowing nitrogen-containing waste products, such as urine that contains ammonia, to accumulate. Current evidence also suggests that the inactivity of winter sleep does not result in the breakdown of bone and the excretion of calcium as it does in other hibernators and in humans subjected to prolonged bed rest. In addition, a hibernating black bear can be aroused if sufficiently disturbed — a crucial adaptation that enables it to protect its cubs, defend itself or flee from predators, and a capability not shared by other hibernating species.

Bears that reside in regions with mild climates show a lesser degree of hibernation than bears in regions with harsh winter climates. During winter months in Missouri, bears become lethargic, decrease their activity and sleep often. During warm winter days, some bears may wake up and wander around for short periods before denning again. However, a bear in a well-insulated den might be less likely to wake from hibernation when temperatures vary. For example, a bear that dens within a natural cave will likely stay in its den for the entire winter season, because caves rarely change in temperature, whereas to a bear that has denned under a fallen tree is less insulated from the weather.

Bears den in a wide range of locations, including caves, hollow trees, tree stumps, brush piles, burrows dug in the ground and, in some cases, a den they create from loose leaf litter. Most dens are just large enough to accommodate a bear when it is curled up to prevent heat loss (Figure 3). Human disturbance of a den will cause a bear to abandon it, but, depending on the time of year, the bear may seek out a new den.

During the winter bears may lose up to 30% of their pre-denning weight before emerging from their dens in search of food. Most bears continue to lose weight during early summer until about mid-June, when calorie rich-foods such as blackberries become available.

Reproductive behavior

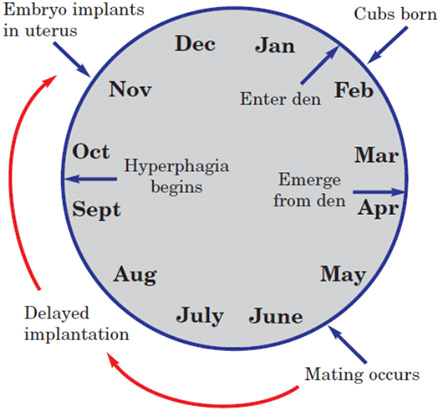

In Missouri, bears mate from mid-May to mid-July. Estrous, the period of time a female is receptive to a male, lasts for about a month. In areas of low bear density, a male will attempt to isolate and defend a female. In areas of high bear density, males and females may both be promiscuous. If a female is promiscuous, it is possible that her cubs, if she has more than one, could have different fathers. This multiple paternity has only recently been discovered to occur in bears. Bears are thought to be induced, or stimulatory, ovulators, which means that the physical act of mating stimulates the female to release eggs from her ovaries.

Although mating occurs in June or July, the fertilized eggs, called blastocysts, do not immediately implant into the wall of the uterus. The development of the embryo is delayed until November (Figure 4). The eggs will implant in November or December if the female has deposited enough fat to sustain herself and her cub(s) through the winter denning period. This reproductive process is called delayed implantation. Due to delayed implantation, the gestation period for black bears is roughly 230 days, or about eight months, but their actual embryonic development occurs during the last two to three months of this period. If the female is in poor physical condition, she will resorb the embryo(s), terminating her pregnancy.

Cubs are born in late-January and February, after only a couple of months in the uterus. The cubs are not well developed at birth: They are 8 inches long and weigh only about 12 ounces — about the size and weight of a can of soft drink — and their ear canals and eyes are closed. Newborn cubs are covered with fine, gray, down-like hair.

Compared to other mammals, bear cubs are very small relative to their mother’s weight. For example, a female black bear weighing 150 pounds is 200 times heavier than her 12-ounce newborn cub. For comparison, a human female weighing 130 pounds is only 19 times heavier than her 7-pound newborn infant. Being born so premature enables the cubs to take advantage of the mother’s highly nutritious milk. Black bear milk is high in fat — about 30% on a dry weight basis. An 8-ounce glass of bear’s milk contains about 900 kilocalories. For comparison, an 8-ounce glass of whole cow’s milk or human milk contains about 600 kilocalories. During hibernation, adult bears burn only fat to fuel their metabolism. Because glucose, a simple sugar, is required for fetal growth, fetal growth is hindered by the mother’s limited ability to make glucose from fat. This metabolic process may have been the determining factor in the birth of very immature young: A bear’s ability to convert fat into glucose is limited, but fat-rich milk is abundant. The sooner cubs are born, the sooner they have access to atmospheric oxygen that allows them to burn fat instead of glucose for growth.

The breeding potential — the number of young produced by a female animal each year — for black bears is low compared with many other mammalian species. Because the young stay with their mother for a year, an adult female may only reproduce every two years at best and may skip an additional year if food conditions are poor. Females typically need body fat levels of at least 15% to 20% of their total body weight to reproduce. First litters are rarely produced until a female has reached sexual maturity, at around 3½ to 4½ years of age. Two cubs is the normal litter size in Missouri, although a litter size of one or three cubs is also common.

Cubs grow rapidly both before and after their emergence from the den. Cubs are generally 2 pounds when they reach 6 weeks of age, 5 pounds at 8 weeks, and 35 to 50 pounds at 6 months (Figure 5).

Only about half of the cubs born each year reach sexual maturity. The primary causes of cub mortality are other bears, especially adult males — cannibalism has been documented in bears — and humans.

Habitat preferences

Black bear habitat is characterized by relatively inaccessible terrain, thick understory vegetation, abundant sources of food in the form of shrub- or tree-borne soft and hard mast, and adequate denning areas. Inaccessible, thick understory vegetation provides protection from harassment. Adequate denning areas contain a variety of den types, including dense vegetation, tree cavities, downed timber, brush piles and rock crevices. In Missouri, black bears are predominantly found in the oak-hickory forests of the Ozark region (Figure 6). However, black bears can be adaptive and use areas with less forest cover and moderate human development. These areas are not ideal for bears, but due to their diverse and flexible diet, bears can still persist in them.

Food habits

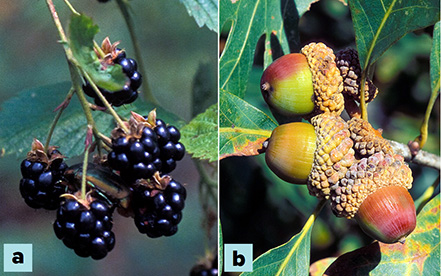

Black bears are omnivores, which means that they can eat plants, animals and fungi. In spring, bears primarily feed on grasses and forbs as these are some of the few food items available when they first wake from hibernation. In addition, bears will feed on a range of insects and insect larvae, such as ants and bees, when they come across them in the woods. Bears will also feed on winter carrion and neonate deer. As spring changes to summer, bears switch to a mix of foods that includes insects, mushrooms and fruiting plants, such as raspberries and blackberries, which are packed with calories (Figure 7a). When autumn arrives, hard mast such as oak acorns and hickory nuts become important as these foods are high in fat and protein, which bears need to put on weight as they prepare for hibernation (Figure 7b).

Although bears eat a lot of vegetation, they struggle to digest it very well. The cells of many plants that bears eat are surrounded by a tough cell wall containing cellulose. Because of the kind of chemical bond that keeps the molecules of cellulose bound together, it is very difficult to digest, at least for most vertebrates, including bears. Deer and cattle have solved the problem of cellulose digestion with their multichambered stomachs that contain a soup of microorganisms that produce an enzyme that breaks down the chemical bonds in cellulose. Bears, however, have simple, one-chambered stomachs that do not contain cellulose-digesting microorganisms. Thus, bears primarily feed on younger herbaceous plants in spring when they are more succulent and less fibrous, making them easier to digest.

For much of the year, bears will consume about 10,000 to 12,000 kilocalories a day to meet their dietary needs, resulting in modest weight gains of 1 to 2 pounds a day. When fall comes, bears enter a biological state known as hyperphagia that results in bears feeding for up to 20 hours at a time and consuming well over 20,000 kilocalories a day. This increase in feed is what allows bears to pack on fat for hibernation, increasing their overall weight by more than 30%.

Home range size and activity patterns

Activity patterns and annual home ranges for bears depend on the availability and quality of food resources, the local bear density and the level of human disturbance in an area. For example, in a place like Missouri, high-quality food resources are abundant and overall bear densities are low, so bears typically do not have to travel far to find food, making their home ranges and daily movements smaller than those of bears that live in areas with limited food resources or high bear densities. Males have larger home ranges than do females because to maintain their larger frames, they need to consume more food, which is usually spread across a broader area. In comparison, female home ranges vary from year to year depending on if they have newborn cubs to care for or if they are in search of a mate. In Missouri, male home ranges cover about 70.6 square miles, on average, whereas female home ranges cover only about 13.5 square miles. Furthermore, bears are typically most active at dawn and dusk when human activity is low but will alter their behaviors to be more active at night in areas of higher human densities.

Managing black bears in Missouri

The Missouri Department of Conservation has developed a Black Bear Management Plan to help guide future decisions regarding black bears. Biologists use science-based methods to collect vital data that guides management decisions, ensuring a self-sustaining black bear population endures while minimizing conflicts with humans (Figure 8). Population models have been developed to annually estimate the bear population and its growth rate. This information provides essential data that informs biologists when setting each year’s annual harvest regulations. In addition, biologists annually put GPS collars on female bears to monitor annual survival rates and track them to their winter dens (Figure 9). Data collected from the collars helps to determine reproductive success, litter sex ratios and cub survival. From this research, it has been determined that about 60% of female bears in Missouri reproduce each year, and they have an average of two cubs. About 70% of the male cubs and 90% of female cubs survive their first year of life.

Research also indicates that bears in Missouri are very adaptive, and as the population increases, they may be more likely to use marginal habitats such as forested areas that are fragmented by agriculture and residential areas. As discussed earlier, bears can move large distances, and research indicates that young subadult bears may travel into these types of areas in search of adequate habitats and, thus, be observed in urban residential areas.

Preventing human–bear conflict

Most conflicts between humans and bears can be avoided. The best strategy for preventing conflicts with bears is to limit access to unnatural foods, such as garbage, bird or pet food, and human foods. When bears have regular access to unnatural foods, they start to become habituated to humans and can become defensive around these food sources. To prevent encounters with bears, it is important to properly secure unnatural foods by either using bear-resistant storage containers, removing bird feeders, placing food items within permanent structures, or installing electric fencing.

Guidelines to follow when in bear habitat

- Never approach a black bear, and don’t let them get close to you. Watch them from a distance. If in a vehicle or home, stay inside. If possible, stay at least 100 yards away from a black bear.

- Keep garbage, pet foods, bird feed and other foods away from bears. Remember, bears that feed on human foods can quickly lose their natural fear of humans. Don’t feed them.

- When hiking in bear habitat, make noise to avoid surprising a bear. Talk, whistle or sing to alert bears to your presence. Leave your dogs at home or, at a minimum, keep them leashed. Dogs can antagonize bears and cause an encounter.

- When camping, keep the campsite clean. Keep food out of your tent. Store food in airtight or bear-resistant containers, and lock food in the trunk of your vehicle or hang it in a tree 15 feet off the ground and 8 feet away from the tree trunk. Wash dishes when you have finished eating. Cook food away from where you sleep. Do not sleep in the same clothes you cooked in. Burn trash only if you are unable to properly secure it; never bury it.

Tips for preventing damage to property caused by bears

- The key to keeping bears away from your house and other buildings is to properly secure food attractants in bear-resistant containers or sturdy buildings.

- Keep trash secure. Store in a secure outbuilding, in a bear-resistant container or behind electric fencing. In addition, wait until the morning of pick-up to put trash out.

- Do not leave pet food or livestock feed out unattended. Store pet food or livestock feed in secure outbuildings, in secure containers or behind electric fencing.

- Remove bird feeders when bears are active, or raise them high enough to prevent bear access.

- Protect bee hives with electric fencing. Be sure fencing is maintained.

Figure 10 provides additional information on bear safety and tips for recreating outdoors in areas with bear populations. To learn more about bears and how to live responsibly with them, go to BearWise, a nationwide program developed and run by bear biologists to share information and resources reflecting sound science and the practical realities of living responsibly with bears.

Conclusion

Black bears have been a part of the natural fauna of Missouri for hundreds of years, and thanks to ongoing research and management activities, populations will continue to thrive within the state. Bears play an important role in the ecosystems in which they occur, and they provide valuable recreational opportunities. Protecting and managing existing bear habitat, modifying land management practices to accommodate the needs of bears, and eliminating bear access to human foods are the primary means by which we can ensure that present and future generations of Missourians can enjoy one of nature’s most spectacular animals.

Additional information

Missouri Department of Conservation

- Hunting and Trapping: Bear

- Report Wildlife Sightings: Bear Reports

- Black Bear Management in Missouri

BearWise

Photo credits: Missouri Department of Conservation