Editor’s note

This publication is also available in Spanish. (Esta publicación también está disponible en español.)

When I was sow farm manager in a 10,000-head unit with a 3,000 gilt-developer unit across the road in eastern North Carolina, it was very challenging to recruit and retain employees in this area. As rural populations decline and fewer young Americans pursue careers in agriculture, producers are facing a growing labor shortage. Around 10 years ago, there was a game changer: the TN-visa program-a legal pathway that allows Mexican professionals to work in the U.S. in specific fields, including agriculture. After that, the farm ran almost fully staffed, and the crew became more stable. These are TN-visa professionals from Mexico, and they are vital for the very complex swine system across the United States.

Nonetheless, little is known about their demographics, previous experience, and professional motivations. Therefore, there was an initiative to conduct research on this unique Hispanic employee population. A recent multi-state survey led by the University of Missouri, in partnership with several land-grant universities, offers a closer look at this workforce.

In total, 260 TN-visa professionals were surveyed using a bilingual tool with a mixed approach-in-person and online, covering fifteen states in the country. The findings reveal interesting facts that can be used to develop bilingual training opportunities, improve management approaches, and create conditions that can better support them to increase retention.

How much TN-visa is utilized in swine farms?

The survey found that around 40% of the total employees hold a TN visa. In North Carolina, for example, they make up nearly two-thirds of the workforce on some swine operations. Meanwhile, in states such as Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa, the utilization of TN visa workers on participating farms was 56%, 37%, 43%, and 59%, respectively.

Who is a TN-visa worker?

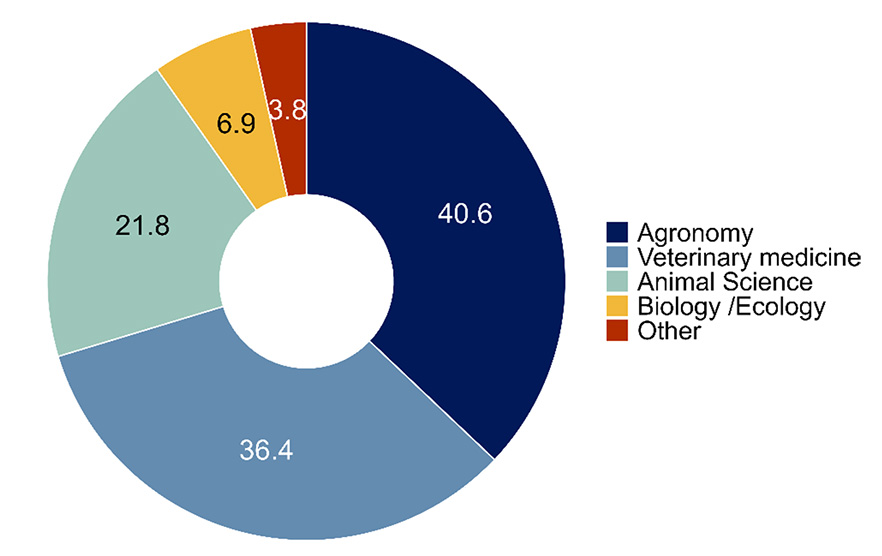

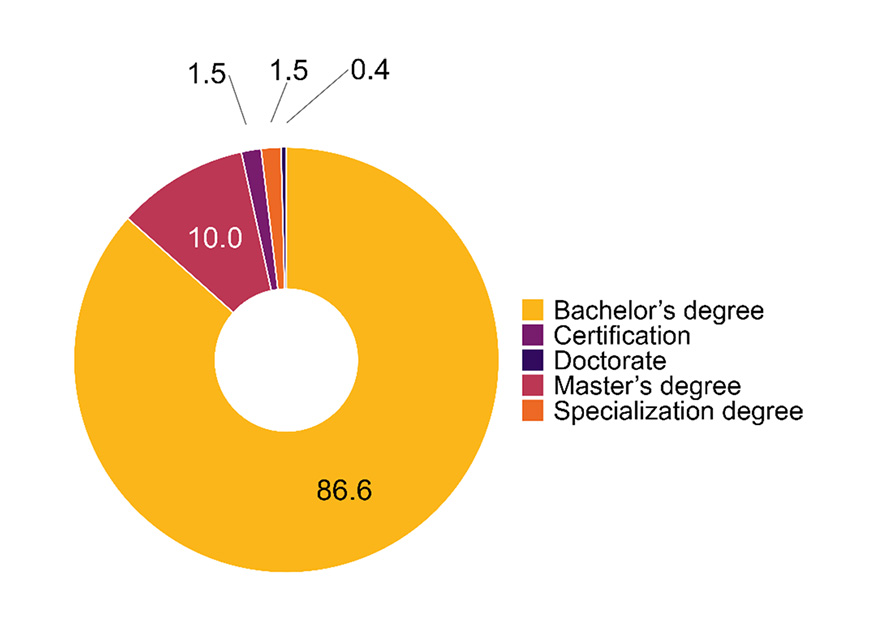

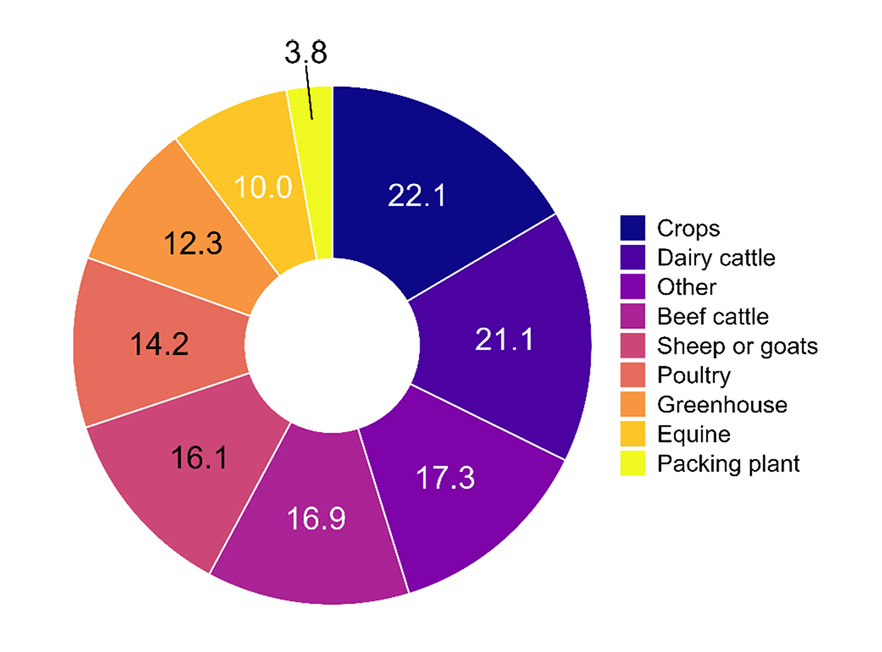

Unlike seasonal laborers, TN-visa workers are highly educated individuals. To qualify for the visa, they must hold at least a bachelor’s degree—often in animal science (22%), veterinary medicine (36%), or agronomy (41%, Figure 1) and 10% of them arrive with a master’s degree (Figure 2).

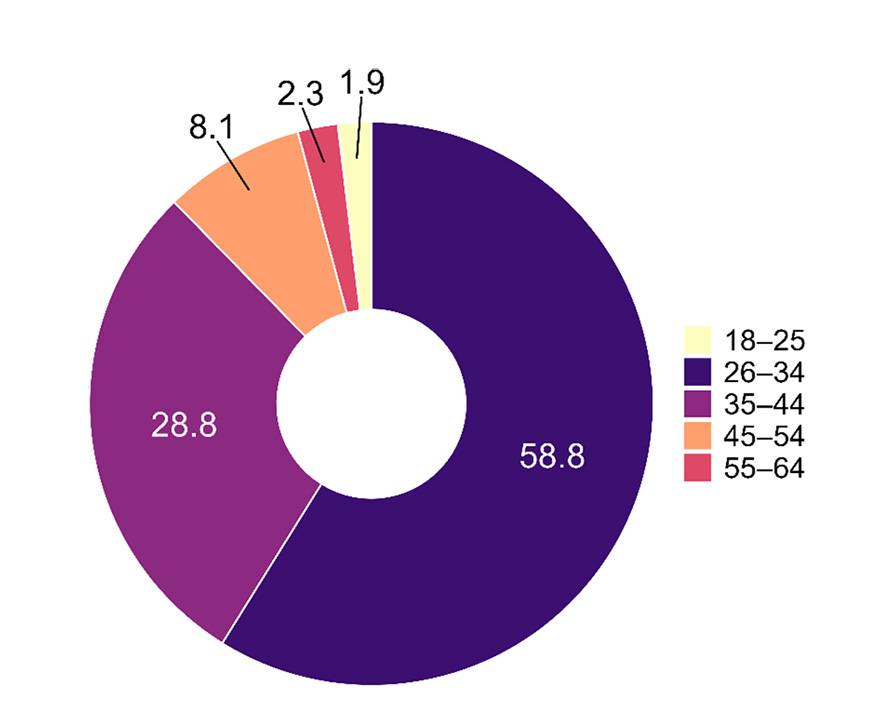

About 60% of them are in their late 20s to mid-30s (Figure 3), making the U.S. swine industry very attractive to Hispanic professionals that are in their early state of their careers. Additionally, roughly 60% self- identify as male and 40% as female.

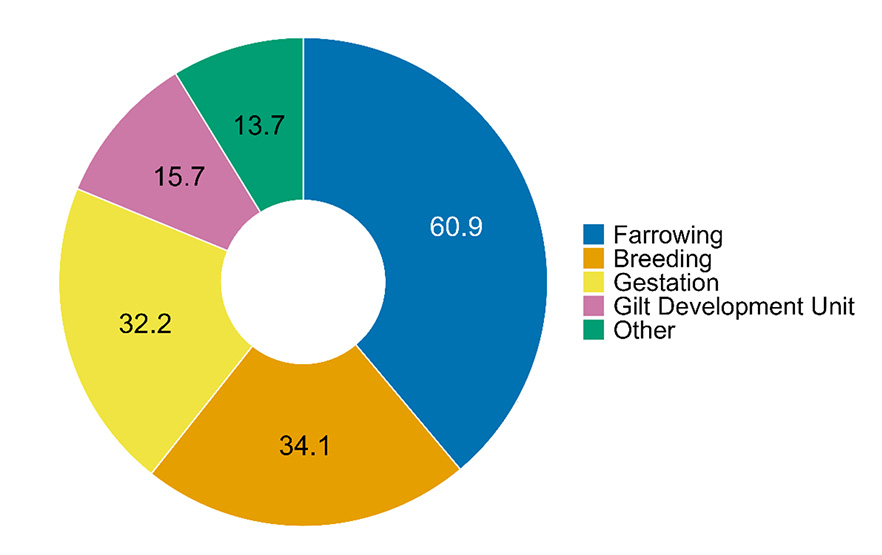

Sixty-one percent of the workers reported working in the farrowing department (Figure 4), which highlights the skills these individuals possess in animal husbandry, record-keeping, observation and problem-solving, attention to detail, teamwork and communication are needed to work in this department.

Interestingly, while many have agricultural and livestock experience (raw crops, beef and dairy cattle, poultry and sheep or goats). Yet, few had worked with pigs before arriving in the U.S. (Figure 5). This is crucial to acknowledge as this experience may enable them to switch swine employers easily within the US or even work for another employer in a varied species. Thus, emphasizing the need to address workplace challenges is necessary for enhancing working conditions to keep these employees.

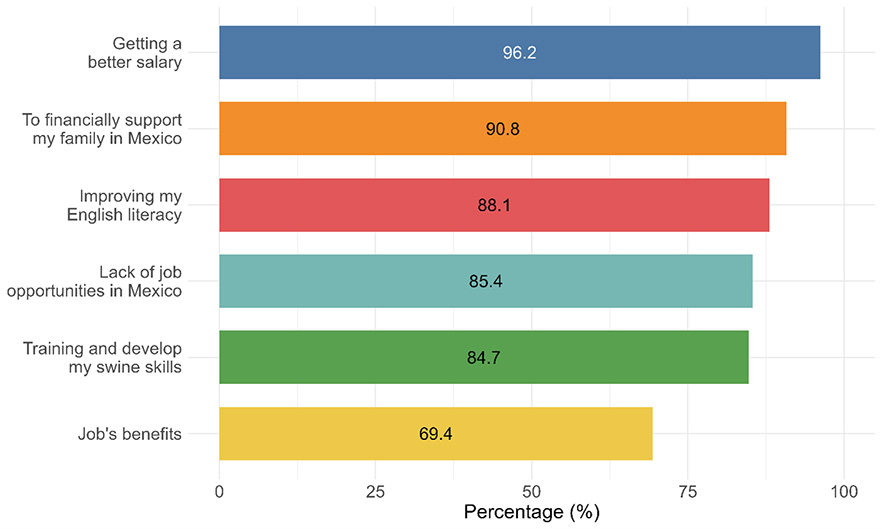

Why are they coming to the US?

The reasons are both practical and personal. Better wages are a major draw, allowing workers to support families back home and save for the future. But many also see the TN program as a chance to learn, grow, and build a career (Figure 6).

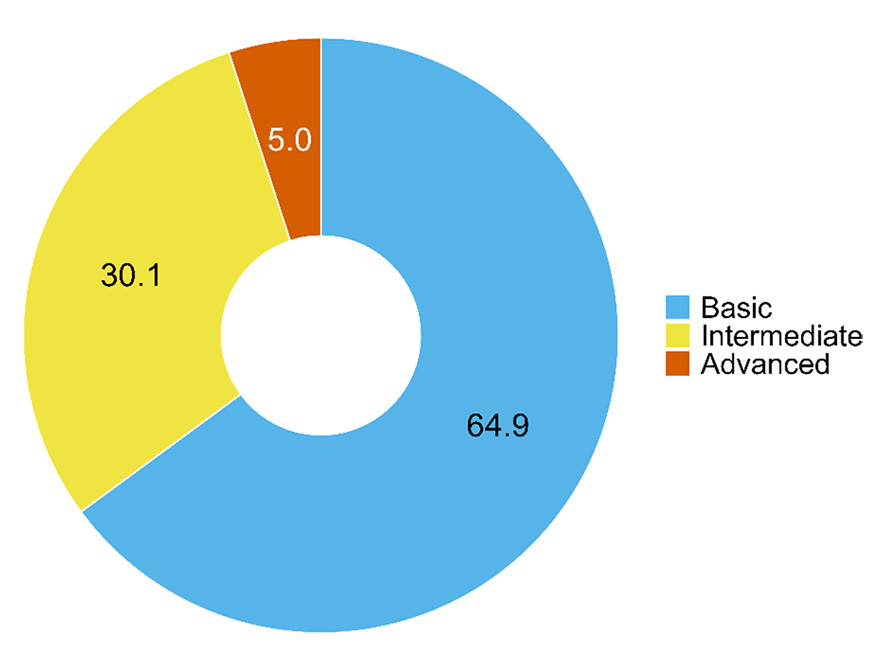

Self-rating English literacy

Language is one of the biggest barriers with 65% of them self-rating their conversational English as basic (Figure 7). This can make it hard to communicate with supervisors, understand training materials, or express ideas and concerns. It also limits their ability to take on leadership roles, even when they have technical skills.

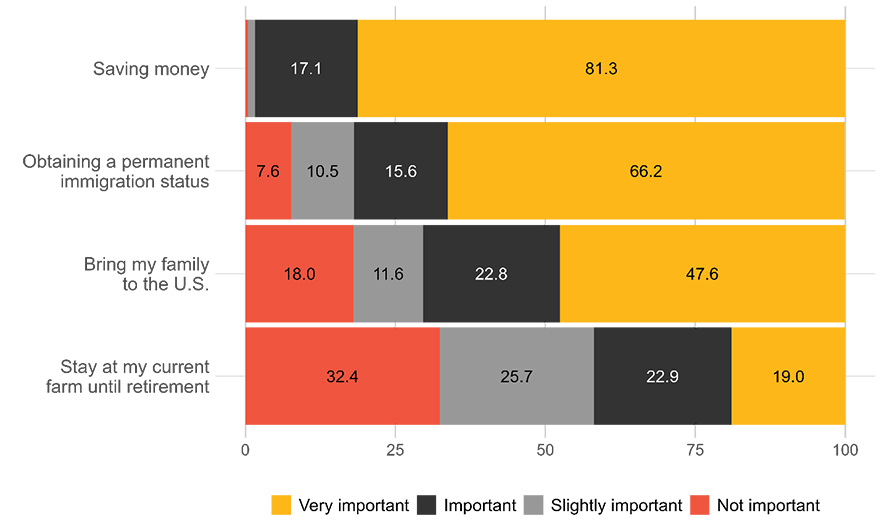

Figure 8 data highlights what matters most to TN visa holders working in U.S. swine farms. The overwhelming priority is financial security, with 81% rating saving money as very important. Immigration stability also ranks high, as 66.2% consider obtaining permanent status very important. These insights signal the need for employers to focus on competitive wages and keep supporting immigration processes are fundamental to retain skilled labor.

What can farms do?

The survey gives some beneficial suggestions to improve retention and job satisfaction among TN workers:

- Invest in customized training: offer leadership and technical training tailored to the backgrounds of TN workers. Bilingual materials translated Standard Operational Procedures (SOPs), and visual aids, can help bridge gaps and build confidence and increase motivation. This may be achieved through partnerships with Extension departments.

- Recognize their potential: trusting in their experience and education, it builds loyalty and trust. Employing them as future leaders may raise morale and performance.

- Create growth opportunities: temporary jobs like "Environmental leader" or "PPE-compliance chief" can encourage employees to feel valued. They also serve as steppingstones for more established leadership roles.

- Foster inclusion: create team-building activities that integrate TN employees and local personnel. Shared meals, bi-lingual meetings, or cross-training exercises are some examples of how to close cultural divides and build closer teams.

Why does it matter?

TN-visa workers are not just a short-term fix for a labor shortage—they are a long-term asset. By understanding their needs and aspirations, swine producers can build more resilient operations, reduce turnover, and improve productivity.

These workers bring more than hands to work on farms they carry wealthy skill set. They look for long-term settlement; they possess knowledge and a deep respect for livestock production. As the industry evolves, remain embracive to this workforce is not just great business—it is essential for the future of American hog farming.

Funding

This project was sponsored by the National Pork Board (NPB Project RFP-0042 – MU Project 00086920).

Team

Talita P. Resende, Magnus Campler, Kara Flaherty, and Andréia G. Arruda: College of Veterinary Medicine, The Ohio State University.

Isaiah Franco, and Douglas Jackson-Smith: School of Environment and Natural Resources, The Ohio State University.

Anna K. Johnson: Department of Animal Science, Iowa State University.

Monique Pairis-Garcia: Department of Population Health and Pathobiology, NC State University.

Samira Chatila, Maria Pieters and Pedro Urriola: Department of Veterinary Population Medicine, University of Minnesota.

Kelly L. Adams, Nahida Begum and Amy Lake: Research Assessment Center, College of Education & Human Development, University of Missouri.

Acknowledgements

This project involved a wide range of people in the pork industry: pork producers, including farm managers and production directors, and Human Resources professionals. To the National Pork Board and its staff, and the Pork State Associations, with special thanks to the Missouri Pork Association. Lastly, to Rob Knox at the University of Illinois – Urbana Champaign.

*This article was published in the National Hog Farmer Magazine in November 2025.