Once-plentiful game bird is making a comeback on some Missouri farms

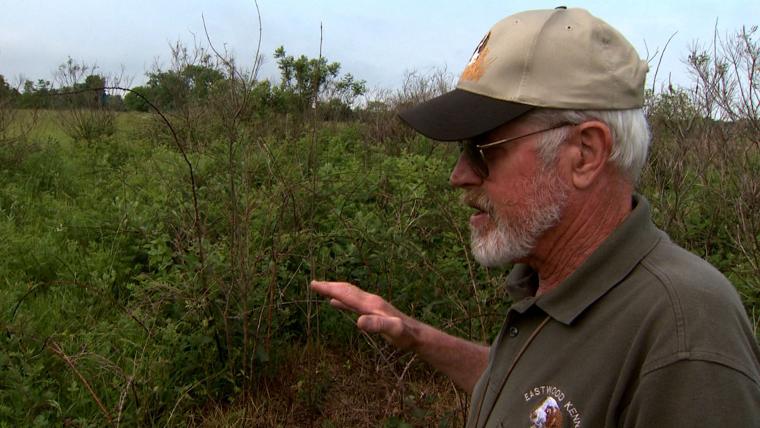

COLUMBIA, Mo. – “If you get up in the morning and you hear quail singing and it doesn’t make your heart lift, you missed out on a big part of what life really is,” says farmer George Hobson.

Modern farming techniques have erased much of the habitat of the once-abundant northern bobwhite quail, but on Hobson’s farm and others like it, the quail population is going up—without dragging profits down.

The 65-year-old Hobson owns 100 acres in Boone County, Mo., where he grows corn, soybeans, wheat and milo. He also has made parts of his farm much more quail-friendly through habitat-management techniques that create the mixture of plant communities bobwhites need for nesting, feeding and protection from predators.

“The misconception for many people is that farmers don’t care about wildlife,” said Tim Reinbott, superintendent of the University of Missouri’s Bradford Research and Extension Center, a 591-acre research farm adjacent to Hobson’s property. “They really do care, because it’s a great indicator of the health of their environment and it creates value for their land.”

Enjoyment of the land and its wildlife isn’t the only benefit for Hobson and other farmers who have enrolled in a U.S. Farm Service Agency initiative that pays them to convert underperforming cropland along field borders into productive wildlife habitat. FSA’s Conservation Reserve Program compensates Hobson for income lost from taking land out of production, and nature has rewarded him with more quail and other wildlife such as rabbits and songbirds.

Quail roost in groups called coveys. Nine years ago, Hobson’s farm had two coveys. Today the farm supports four coveys, for a total population of about 40 quail..Results have been even more dramatic at Bradford Farm, which for the past several years has been a laboratory for practices that integrate wildlife habitat into modern farm operations. Last fall, staff and volunteers logged pre-dawn calls from an estimated 26 quail coveys.

That’s in sharp contrast to Missouri’s overall quail population, which has fallen as much as 70 percent in the last three decades. “But we’ve shown that farmers and landowners can reverse that with management practices that don’t cost a lot of money and take up just a small amount of space,” Reinbott said. “A 30-foot buffer along fence rows, along wooded edges, is enough to provide much of the nesting, brooding, feeding and escape cover that quail and other wildlife need.

“For so long, we had conservation on one side and agriculture on the other and they really couldn’t meet in the middle,” he continued. “We have shown here at Bradford Research Center that when conservation and agriculture get together, good things can happen.”

Reinbott notes that quail habitat management is not hard, just different from what most farmers are used to. “Corn, soybeans, wheat—they’re annual crops. You plant them and you see your results within just a few months. Planting wildlife habitat, you might not see real benefits for two or three years. You have to be patient, but you will see those benefits and they will be long-lasting with minor management in the years thereafter.”

Hobson said that even landowners with smaller holdings can make a difference, especially by teaming up with neighbors. “Guys with 25-30 acres can do a lot. With just a little effort on each of their parts, we can bring back quail to a much larger geographical area.”

For more information, see the MU Extension guide “Habitat Management Practices for Bobwhite Quail.”