COLUMBIA, Mo. – Some gardeners take a hands-off approach to leaves. But leaves left on lawns can pack down into a tight mat, preventing sunlight from reaching the grass, says University of Missouri Extension horticulturist David Trinklein. Leaves also trap and hold moisture, which increases the potential for disease.

However, tree leaves can be a valuable asset to gardeners who want to start a compost pile or add nutrients to lawns, Trinklein says.

First, clear the lawn by mowing damp leaves. Adjust your mower to its highest setting and mow in a crisscross pattern. Mow twice to cut leaves to confetti-size pieces. These small pieces will filter into the lawn, decompose and release nutrients for the grass.

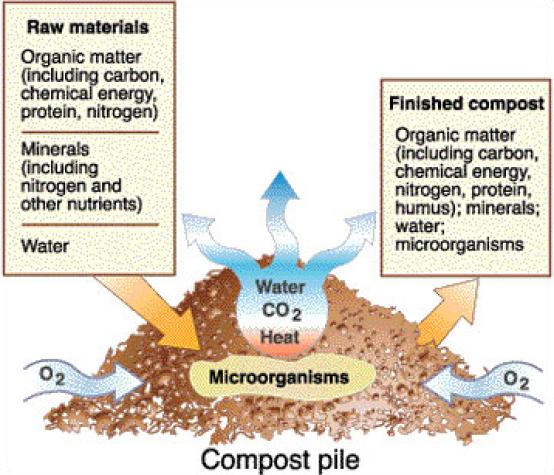

Another option is composting. Compost is created when soil-inhabiting microbes break down plant tissue. When added to soil, compost binds small clay particles together into larger particles. This improves soil aeration, root penetration and water flow in clay-type soils like those found in much of Missouri.

Soil microbes need ample carbon and nitrogen to form compost. Most leaves are high in carbon but low in nitrogen. Adding nitrogen to the compost pile can speed up the decomposition process. This can be accomplished with a general-purpose fertilizer such as 12-12-12 at a rate of about 2 pounds per bushel of leaves, or by adding 1-2 inches of animal manure or green plant material such as grass clippings.

Construct the compost pile in layers, starting with about 4-6 inches of well-shredded leaves followed by a layer of the nitrogen source. Repeat until the pile is 36-48 inches deep and covers an area of about 25 square feet.

If you want to enclose the compost pile, you can buy specialized composting bins, but wire mesh, concrete block or treated lumber enclosures also work well, Trinklein says.

Water each layer as you add fertilizer. “A properly constructed compost pile should feel damp to the touch, but not wet,” he says.

If using manure as a nitrogen source, make certain of its history. Some herbicides used in pastures and hayfields pass through the digestive systems of animals and remain in the manure in amounts large enough to damage sensitive species like tomato.

Trinklein says carbon and nitrogen make soil microbes “go bananas,” and their activity will heat up the compost pile. When composting is done correctly, the temperature at the center of the pile should reach about 135-140 F, enough to kill weed seeds, most pathogens and insects.

Decomposition wanes as the microbes run out of food. The compost pile begins to settle and cool, indicating the pile is ready to be turned. Use a rake or shovel to move partially decomposed leaves from the outer edges of the pile to the center. This renews microbial activity, so the pile will heat up again. Decomposition is complete when the pile fails to heat after being turned.

Leaves may not decompose completely before cold weather sets in, but the process begins again when air temperatures rise in the spring.

Some leaves may be used as mulch for tender plants such as azaleas and rhododendrons. Trinklein says stiff leaves such as those from oak trees do not mat and work best for mulch. Put leaves in a wire cylinder around the plant to keep them in place.

The MU Extension publication “Making and Using Compost” is available for free download at extension.missouri.edu/publications/g6956.