If I applied earlier than normal, am I in trouble?

COLUMBIA, Mo. – High nitrogen prices and concerns about fertilizer supplies have disrupted nitrogen management for the 2022 growing season.

“For corn, there were many reports of anhydrous ammonia being applied earlier than normal and that more nitrogen was applied in the fall than normal,” said John Lory, University of Missouri Extension nutrient management specialist. “Nitrogen applied in November waits in the soil over six months before the corn plant really needs it.”

Optimal nitrogen management for corn focuses on split applications between planting and side-dress or focusing only on side-dress applications, said Lory. These “4R” strategies (right source, right rate, right time, right place) shorten the time between nitrogen application and when the plant needs the nitrogen, limiting opportunities for nitrogen loss.

Fall application remains a common practice up north, in Iowa and Minnesota, where soils remain at or below freezing at 6 inches in January and February and often are near freezing for most of December and March.

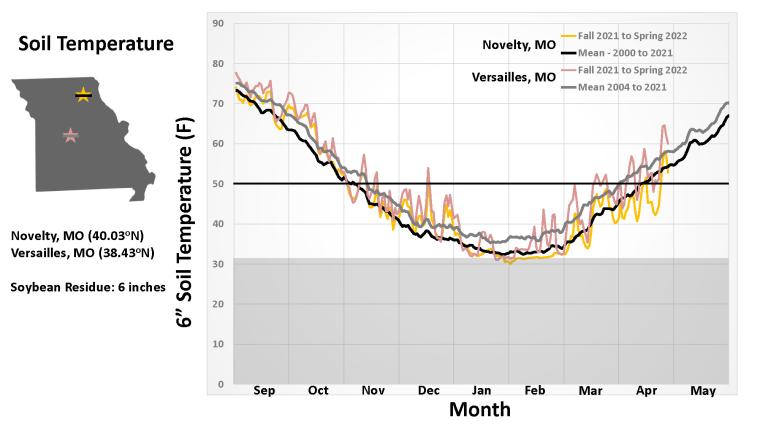

In contrast, in northern Missouri, at the MU Extension weather station at Novelty, the long-term average for 6-inch soil temperatures under soybean residue frequently is over 32 degrees. In central Missouri, at the MU Extension weather station at Versailles, the long-term average soil temperature at 6 inches never falls below 35 degrees, and in some years soil temperature is frequently above 40 degrees.

“Under these conditions, soil temperatures often are not cold enough to keep your nitrogen safe over winter and into the spring,” Lory said.

So, what does it mean when anhydrous ammonia was applied last fall in Missouri?

The warmer soil makes it more likely that substantial amounts of fall-applied nitrogen will convert to nitrate in the fall or by early spring. As a rule, the earlier you applied and the farther south you are in Missouri, the sooner your fall-applied nitrogen will convert to nitrate. Anyone who applied nitrogen in the northern two-thirds of Missouri in September and October likely had some or all of their nitrogen convert to nitrate by January, even if they used a nitrification inhibitor.

Farmers who applied in northern Missouri starting in November or in central Missouri starting in December, and used an inhibitor, likely held their nitrogen as ammonium into spring. Otherwise, farmers in northern and central Missouri who applied in November or later likely had significant conversion to nitrate over late fall and winter.

The good news in early May is that in most fields, fall-applied nitrogen is likely still there, although it is fully converted to nitrate, Lory said.

“The bad news is that for many fields, the corn plant cannot use that nitrogen for another six to eight weeks or more,” Lory said. “There is potential on some soils that nitrate has leached deeper into the soil or, on soils with lateral flow, been carried downhill. As soils warm above 60 degrees, saturated, warm soils lead to our biggest source of nitrogen loss – denitrification. Fifty percent or more of nitrogen can be lost in days when warm soils remain full of water for two to five days. These losses are most common in May and June.”

He notes that side-dress nitrogen applications are specifically designed to minimize risk of denitrification loss by occurring closer to when the plant needs fertilizer.

To manage risk from preplant and fall nitrogen applications, pay attention to wet periods in May and June that saturate the soil, he said. Watch for signs of nitrogen deficiency that align with wet areas in the field. Corn color can be an effective indicator of corn nitrogen status, especially when compared to a well-fertilized area of the field.

Extensive MU research shows the cost-benefit of rescue side-dress applications where there are significant losses.

For 2023, Lory recommends considering a management system that allows you to apply at least 50% of your nitrogen to corn that is at least knee-high.

Graph:

Soil temperatures

Soil temperatures in northern and central Missouri, September-May.

Writer: Julie Harker