Traditionally, when the topic of hair shedding arises, it is in the context of mitigating summer heat stress among cattle in the southeastern U.S. while grazing toxic fescue. This is not in error. It is estimated that cattle suffering from fescue toxicosis and heat stress alone cost the beef industry over a billion dollars a year. This makes hair shedding an economically relevant trait in cattle.

As research into hair shedding continues, more information about its importance becomes known. Most recently, a relationship between hair shedding in cattle and their ability to sense change in daylight has been discovered. This suggests that cattle who shed their winter coats earlier are more able to adapt to their environment making hair shedding an indicator trait in cattle regardless of location.

This MU Extension guide is meant to 1) provide background information on the economic importance of hair shedding scores, 2) introduce the hair shedding (1-5) scoring system, 3) discuss how to implement hair shedding into a selection program, and 4) promote hair shedding as a management tool.

Hair Shedding as an Economically Relevant Trait

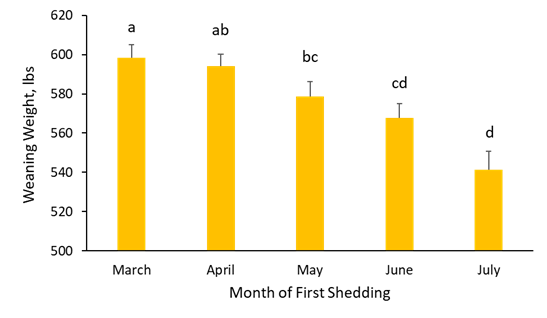

Anytime a trait can directly be linked to profitability, it is characterized as economically relevant. In the case of hair shedding, cows who shed their winter coat earlier tend to wean heavier calves (Genetic correlation = -0.19). Figure 1 shows the average weaning weight of calves born to dams who began shedding their winter coats between March and July. The average weight of a calf born to a dam that shed in March was 57.2 lbs heavier than those that shed in July.

Most research that investigates the relationship between hair shedding and profitability target weaning weight because it encompasses many different production issues created by heat stress. To start, cows who undergo heat stress in the summer are less likely to get pregnant early in the breeding season. This could be due to low body condition scoring (BCS) because of heat stress while grazing summer pasture before fall breeding, or directly due to heat stress during spring breeding. Regardless, cows bred later in the season also calve later and therefore wean lighter calves.

Secondly, cows who undergo stress after calving may see an impact on milk production, which also impacts weaning weight.

Hair Shedding and Environmental Adaptability

Because increases in temperature happen at the same time hours of daylight are increasing, it is difficult to identify whether animals start shedding due to changes in temperature or daylight. Recent research conducted at the University of Missouri investigated the relationship between the DNA of the animal and temperature 30 days prior to the collection of a hair shedding score. This analysis only identified 17 interactions between DNA and temperature that influenced hair shedding. In a second analysis, researchers instead investigated the interaction between the DNA of the animal and the average length of daylight 30 days before the hair shedding score was observed. This time, there were 1,040 significant DNA-by-daylength associations identified. This supports the idea that cattle shed their winter coats in response to increasing amounts of daylight instead of a drop in temperature. This association is important because it promotes hair shedding as an indicator of an animal’s ability to sense and respond to their environment.

Hair Shedding Scores

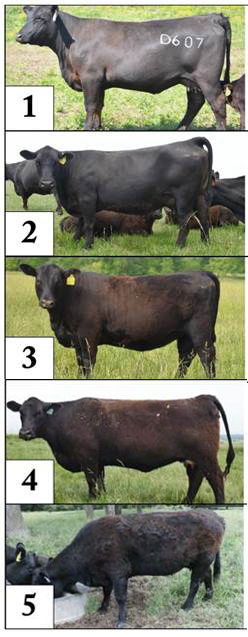

What/How: Hair shedding scores represent a visual appraisal of the extent of hair shedding and are reported on a 1 to 5 scale (Figure 2) in which:

- 1: Cattle have shed 100% of their winter coat. All that remains is a shorter, smooth, summer coat.

- 2: Cattle have shed 75% of their winter coat, with a small amount of hair left on their flank and hindquarter.

- 3: Cattle have shed approximately 50% of their winter coat. In addition to the hair along the neck, this will include hair along the body, often in patchy spots.

- 4: Cattle have shed only 25% of their winter coat. This will mainly occur around their neck but may also include their topline.

- 5: Cattle have shed 0% of their winter coat. Thick, longer hair still covers their entire body.

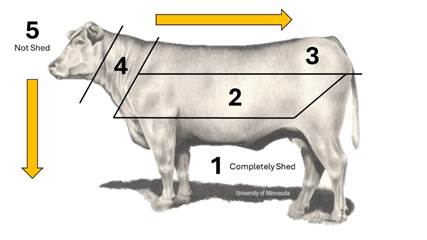

Half scores, such as 3.5, are not reported. In general, cattle tend to shed hair from the front to the back and from their topline to their belly (Figure 3), but there is individual animal variation in this pattern. Typically, animals begin shedding around their neck, followed by their topline. The last spots to shed are an animal’s lower quarter above its hock and its underline.

When: It is only necessary to collect hair shedding scores once in late spring or early summer. The date to evaluate cattle for shedding progress will vary by geographic location and environmental conditions. The goal should be to score cattle when there is the most variation in hair shedding within a herd. In other words, a few animals with a hair shedding score of 1 or 5 with a majority receiving a hair shedding score of 3. Mid-May has been identified as an ideal hair shedding evaluation period for cattle in the Southeastern U.S. As a rule of thumb, the hotter and more humid the climate the earlier in the spring scores should be collected.

Who: If using hair shedding score as a selection method or reporting scores to a breed association, all cows in the herd should be observed. While it is recommended to score all animals in a herd on the same day, it is important to keep in mind that males tend to begin shedding a few weeks prior to females and therefore should likely be scored separately.

Where: Being a subjective observation of the amount of hair an animal has shed, these scores are easy to collect. This can be done as cattle pass through a chute during routine handling timeframes or while out on pasture.

Methods of Selecting for Hair Shedding

As a moderately heritable trait (h2 = 0.35 to 0.42), producers can expect to create positive genetic change in their herds by simply adding hair shedding scores as a selection criterion when making selection decisions. To do this, producers would need to assess the hair shedding score of the whole herd on the same day, consider culling older animals with higher scores (more hair), and selecting the replacement heifers who shed earlier in the season in addition to other components of interest.

In addition to phenotypic selection, some bulls will also have an expected progeny difference (EPD) for hair shedding available for use. If available, selecting bulls with a lower hair shedding EPD will result in daughters born who shed earlier in the season, on average.

Hair Shedding and Age

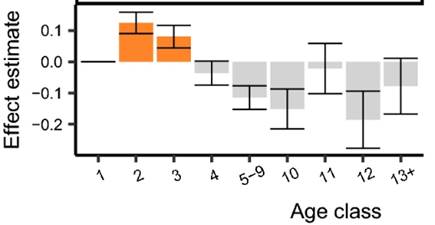

When using hair shedding as a selection criterion, it is important to also consider the age and nutrient requirements of the female. Yearlings and first-calf heifers tend to have higher hair shedding scores compared to older, established cows (Figure 4). This does not mean younger females are necessarily worse shedders than their dams. Younger cows are, by default, the most nutritionally stressed as they are growing and raising a calf while also growing themselves. Therefore, it may be more beneficial to rank and select younger females within their age group instead of comparing them to older herd mates.

When evaluating the effect of age on hair shedding score, the average score for each age group tends to decrease as age increases (Figure 4). This could reflect the impact of late shedding on production. Cows who shed their winter coats later in the summer may have fallen out of the herd due to weaning lighter calves, failure to conceive, or low body condition.

Hair Shedding as a Management Tool

It is anticipated that hair shedding scores could be used in conjunction with body condition scores to assess the current nutritional stress of the herd. Genetic associations were also discovered between hair shedding and functions related to metabolism. Therefore, hair shedding may also pose as an indication of an animal’s overall nutritional plane, thus helping to inform management decisions. It is no coincidence that younger females shed their coats later than their older herd mates. Similarly, older cows who may have had a ‘hard winter’ would shed later in the year. The repeatability of hair shedding is only 45%, which indicates over half (55%) of the variance in hair shedding is due to year-to-year differences in management and environment of the cow. Understanding that later hair shedding (higher scores) indicates increased nutritional demands could be used to identify animals who would benefit from additional supplemental feed heading into spring and summer.

Conclusion

Although hair shedding has traditionally been associated with heat stress and fescue toxicosis, recent research shows this quick and easy phenotypic assessment of cattle could be a trait of even more economic importance. Producers wishing to select females based on hair shedding scores can do so based on a simple 1 to 5 scoring system. With its moderate heritability, combining this score with a hair shedding EPD or score on bulls would result in positive genetic progress over time.

More detailed information on the scoring system and some frequently asked questions can be found in publication G2041, How to Use the Hair Shedding Scale.