Anthracnose basal rot

Symptoms and signs | Conditions | Management

Anthracnose basal rot is a destructive crown rotting disease of creeping bentgrass and annual bluegrass on putting greens. On mixed bentgrass/annual bluegrass putting greens, the causal fungus infects one species or the other but rarely both (Figure 1). In the Midwest, the disease has been observed more often on creeping bentgrass than on annual bluegrass.

Colletotrichum cereale is commonly observed on senescing tissue of many grass species, including those grown as forage crops. When diagnosing anthracnose basal rot on putting greens, it is important to differentiate between an active infection and a secondary infection on damaged, senescing or dead tissue.

Pathogen

- Colletotrichum cereale

Hosts

- Creeping bentgrass

- Annual bluegrass

Symptoms can be confused with those of

- Copper spot

- Red leaf spot

- Moisture stress

- Heat stress

Symptoms and signs

From a distance, infected annual bluegrass appears unthrifty and has a yellow or bronze cast (Figure 2). Infected bentgrass first appears purple to reddish brown, resembling a dry spot (Figure 3). The symptoms on the green often appear as a patch, because the fungus differentially infects annual bluegrass or susceptible selections (clones) of creeping bentgrass on the putting surface. Bentgrass within the affected patches is thinned.

Colletotrichum cereale produces acervuli (fruiting structures) on leaves, stems and crowns (Figure 4 top). Acervuli are surrounded by sterile setae (black, hairlike structures) (Figure 4 middle). Setae are easily visible with a 20X hand lens, so turfgrass managers and other turfgrass professionals often use the observation of setae to diagnose the disease. To determine if the disease is active, however, it is necessary to examine the acervuli for viable conidia (spores), which are produced in a gelatinous matrix on the surface of the acervuli. The conidia are single celled and crescent shaped and can only be seen under high magnification (Figure 4 bottom). This usually requires the assistance of a turfgrass pathologist. Another indication that the disease is active is the observation of sporulation in green tissue (Figure 5).

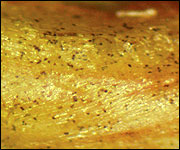

Conidia germinate to form darkly pigmented appressoria (infection structures). The presence of appressoria under the leaf sheaths on green tissue is another indication that the disease is active. Appressoria are abundant on lower leaf sheaths and appear through a hand lens as small pepperlike dots (Figure 6). A close-up reveals the germ pore (Figure 7) through which C. cereale penetrates host tissue.

Crowns, old stems and roots of bentgrass or annual bluegrass appear black due to the presence of mycelial mats (aggregate hyphae) and other fungal structures in this tissue (Figure 8).

Conditions

Anthracnose basal rot most often develops during the warm, humid weather of midsummer, but it may occasionally occur during cool weather. Disease development is usually associated with predisposing factors such as high temperature and humidity, excessive soil moisture, low mowing heights and soil compaction, all of which stress the turfgrass. The disease also tends to be more severe in situations where the greens have been allowed to dry out. The fungus has been observed to overwinter in crowns and roots. Infected but symptomless plants may survive until they are exposed to stress conditions.

Management

Anthracnose basal rot is one of the more difficult diseases to control, especially after symptoms appear. The best strategy to prevent outbreak of this disease is to combine cultural practices that reduce turfgrass stress with a preventive fungicide program.

Turfgrass grown at optimal nutritional levels is less likely to be damaged. Therefore maintain balanced fertility. Do not starve the turf, especially of nitrogen, during the summer months. Light nitrogen application (0.1 pound per 1,000 square feet) during the summer may help the turfgrass withstand stresses and recover quickly from anthracnose basal rot damage.

Low, frequent mowing can enhance disease development. Recent studies indicate that raising the mowing height, even to 5/32 inch, can help reduce turfgrass stress, which in turn can decrease anthracnose basal rot severity. Avoid double cutting on greens with a history of the disease. Mow the perimeter of the green every other day to prevent compaction. Don't mow when the greens are wet if C. cereale is active. Also suspend topdressing activities, because physical damage can result in more severe infection. Some research results suggest that use of the growth regulator trinexapac-ethyl during the season can reduce disease severity on annual bluegrass. Under heavy disease pressure, however, it is best to suspend growth regulator programs to promote recovery.

Anthracnose basal rot tends to be more severe on putting greens with poor air movement and slow infiltration rate. On greens with a history of the disease, consider a rigorous core cultivation program in fall and spring. Compacted greens may be periodically cultivated by spiking, slicing, or hydro-jecting, but avoid excessive injury to the turf during periods of stress. Don't overwater putting greens either by irrigation or by supplemental hand watering. Excessive soil moisture can damage roots and decrease the rate of photosynthesis. This puts the grass into a decline and predisposes it to infection. Monitor greens regularly for dry spots, especially in the early spring. Anthracnose basal rot often begins in areas that have undergone moisture stress. Application of a wetting agent can help with moisture management.

On greens with a history of anthracnose basal rot, a preventive fungicide program is necessary. In most regions, it is advisable to begin this program in mid-April. Refer to Table 5 for a list of fungicides labeled for anthracnose control. All products work best when applied on a preventive or early curative schedule. Applications after development of severe damage to putting greens are not very effective. The most rapid improvement from anthracnose damage occurs following significant (cooler) weather changes, which promote turfgrass recovery. Some strains of C. cereale resistant to MBC, DMI and QoI fungicides have been reported. Avoid sequential applications of these products and tank mix with a contact fungicide to reduce the selection of resistant populations.

Reports suggest that the preemergent herbicides bensulide and dithiopyr increase disease severity.