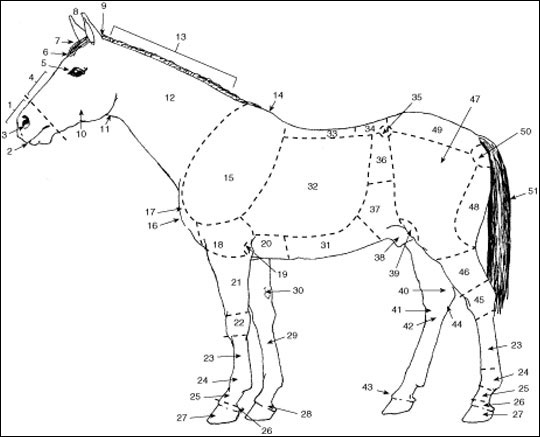

When evaluating the conformation of a horse, you should consider the following areas: balance, muscle, structural correctness, and breed and sex characteristics (Figure 1). Fads at times have skewed the importance of one trait or another, but all are important whether you are looking at a prospective halter horse or performance horse.

- Muzzle

- Lips

- Nostril

- Face

- Eye

- Forehead

- Foretop

- Ears

- Poll

- Jaw

- Throatlatch

- Neck

- Crest

- Withers

- Shoulder

- Breast

- Point of shoulder

- Arm

- Elbow

- Fore flank

- Forearm

- Knee

- Cannon

- Fetlock joint

- Pastern

- Coronet

- Hoof

- Seat of sidebone

- Seat of splint

- Chestnut

- Abdomen

- Ribs

- Back

- Loin

- Point of hip

- Coupling

- Hind flank

- Sheath

- Stifle joint

- Seat of thoroughpin

- Seat of bog spavin

- Seat of bone spavin

- Seat of ringbone

- Seat of curb

- Hock

- Gaskin

- Thigh

- Quarter

- Croup

- Point of buttock

- Tail

Balance

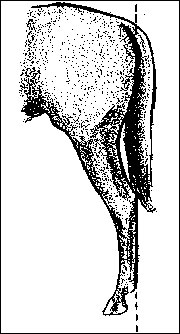

Balance refers to the even, smooth blending of all parts and muscling (Figure 2). Balance is determined by the length of the neck, the back and the croup. Of utmost importance is that the angle of the shoulder should be adequate. Many breeders believe that the slope of the shoulder will determine a horse's agility, because the slope defines the length of the neck. If the slope of the shoulder is too steep, the neck will appear short and the back long. The angle of the shoulder will also be the angle of the pastern. If the shoulder is steep, the angle of the pastern will be steep, which results in a rough, short stride. A horse with a long, moderately sloping shoulder, will typically have a long neck, a short back and a smooth stride. The length of the neck determines the length of the stride as well as the horse'sflexibility. In a performance horse especially, the neck must be long to allow for proper flexing at the poll, which is required in any performance event.

The back should be short and strong with a long underline (Figure 3). The horse should have a long, moderately sloping croup. The length of the croup is important because it is essentially the "engine" that powers an equine athlete. A long croup more readily accommodates more muscle mass.

Balance also accounts for the evenness of muscling. All the parts of a horse's body should blend smoothly into each other and present a pleasing picture.

Mass and internal body capacity

A horse's muscling should be long patterned and defined. Muscle mass can most easily be determined when viewed from directly in front of or behind the horse. As viewed from the front, the horse should show significant width from shoulder to shoulder, a large circumference to the forearm, and a prominent "v" in the front muscling. As viewed from the back, the horse should be wide from stifle to stifle, and the quarter should tie in deep to strong gaskins.

When viewed from the side, a horse should have strong forearms, a deep quarter, strong gaskins, and a long croup to accommodate a large amount of muscle mass through a prominent stifle. In addition, the horse should have a large-circumference heart girth.

For halter horses, the more muscle mass the better. For performance horses, muscle mass should be no more than adequate to perform the tasks at hand, because increased muscle bulk detracts from the fluidity of the horse's stride.

The internal body capacity of a horse determines the room available for lung and heart functions. The more lung capacity a horse has, the more air it can take in with each stride, making the horse capable of more powerful and efficient performance and greater stamina. Internal body capacity also determines the ability of a potential broodmare to carry a large foal.

Structural correctness

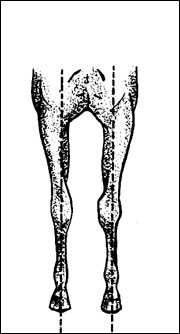

Structural correctness affects the action and soundness of horses. When the front legs are viewed from the front, a line should bisect the forearm, knee, cannon, fetlock and the bulb of the heel (Figure 4). If the toes point outward, the horse is splay-footed; if the toes point inward, the horse is considered pigeon-toed. Typically pigeon-toed horses wing out and splay-footed horses wing in when walking. When the front legs are viewed from the side, the knees should be flat.

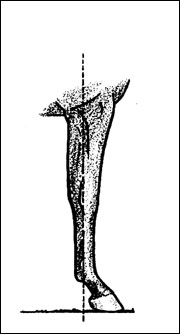

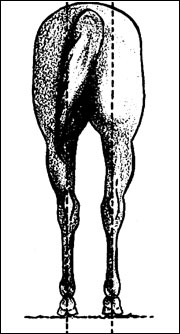

When a horse is viewed from behind, a line should bisect the gaskin, hock, cannon, fetlock, pastern and foot. If the horse's hocks turn inward, the horse is considered cow-hocked. When the legs are viewed from the side, a straight line drawn downward from the back of the buttock should touch the back of the hock, cannon and fetlock. If the horse has too much angle in the hocks, then it is considered to be sickle-hocked. If the leg is forward of this line and too straight, the horse is considered post-legged.

Pasterns should be of medium length, be strong but flexible, and have a medium slope. The hoof should have the same angle as the pastern and should be of moderate size but deep and wide at the heel, and free of rings. The slope of the shoulders and pasterns, combined with the expansion of the heel, provides shock absorption when the horse is in motion. Bones should be of adequate size and should show definition of joints and appear flat when viewed from the side.

Deviation from these points of structural correctness predisposes a horse to unsoundness and wasted motion. Bone spavins, bogs, thoroughpins and weakness are common among sickle-hocked horses. Jarring from short, straight pasterns and shoulders predisposes a horse to side bones, stiffness, bogs and lameness.

Breed and sex characteristics

Breed and sex characteristics of a horse define its quality. A horse should exhibit the characteristics that progressive breeders look for — in short, the breed's icon. Quality is indicated by refinement of head, bone, joints and hair coat. It is reflected in thin skin, prominent veins, and the absence of coarseness, especially in the legs. A quality horse has more attractiveness and eye appeal, including prominent sex characteristics. A stallion should appear more powerful and stately than a mare. A stallion's head should have a masculine jaw, whereas the mare should be a picture of refined femininity. The gelding falls between the two.

Summary

An outstanding horse will exhibit superior conformation whether it is a halter horse, pleasure horse or racehorse. Some horse judges support fads and are more forgiving of certain faults than others. However, a horse's form is related directly to function. In the long run, whenever you sacrifice certain qualities of conformation, a limitation in ability will occur. When evaluating horses, the ideal will always be in demand; there is no substitute for quality.

This publication was revised with the assistance of Jennifer Nabors.