Fact sheet 3

There are more than 400,000 private wells in Missouri, accounting for more than 17 percent of the state's water supply. These wells are used by more than 1.4 million Missourians, more than a quarter of the state's population.

In 1994 the Missouri Department of Health released a survey of private drinking water wells by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that found that many Missouri wells were at risk of contamination by bacteria and nitrates. Researchers tested at least eight wells in every Missouri county, including wells of four different construction types: bored, hand-dug, drilled and sand-point.

According to the department's findings, of the 861 private drinking-water wells sampled, 481 (56 percent) tested positive for total coliform bacteria and 189 (22 percent) tested positive for E. coli (human/animal manure bacteria). Missouri is geologically diverse, yet contaminated wells were found in all geologic areas of the state.

Keeping your well water free of harmful contaminants is a top priority for your health and for the environment. This guide helps you examine how you manage your well and how activities on or near your property may affect well water quality. The following topics are covered:

- Part 1

Well location

How close is your well to potential pollution sources? How might your soil type affect water quality? How does the local geology of your area affect the risk of contamination of your well? - Part 2

Well construction and maintenance

Do you know how old your well is and what type of well it is? Is your well casing properly sealed? Do you have records stating the depth and geologic profile of your well? - Part 3

Water testing and unused wells

Has your well been tested recently? If so, what tests were done? Have tests of your well water revealed any problems? Are there any abandoned wells on yours or your neighbor's property? Are abandoned wells protected against contamination?

Why should you be concerned?

A large number of Missouri's rural residents use private wells to supply drinking water. These wells, which tap into local groundwater, are designed to provide clean, safe drinking water.

However, improperly constructed or poorly maintained wells can create a pathway for fertilizers, bacteria, pesticides or other materials to enter the water supply. Once in groundwater, contaminants can flow from your property to a neighbor's well, or from a neighbor's property to your well.

Contaminants often have no odor or color, so they can be hard to detect. They can put your health at risk, and it is difficult and expensive to remove them. Once your water becomes contaminated, the only options may be to treat your water after pumping, drill a new well, or get your water from another source.

Protect your drinking water and home environment

This guide will help you better understand the condition of your well and how you take care of it. The accompanying work sheet will help you identify situations and practices that are safe as well as ones that may require prompt attention.

Additional information on how to safeguard all water sources may be obtained from local MU Extension centers, county health departments, Soil and Water Conservation District staff, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources Missouri Geological Survey (MGS), federal environmental agencies and the library.

Part 1

Well management

Well location

Your well's location in relation to other features on or near your property will determine some pollution risks. The nearness of your well to sources of pollution and the direction of groundwater flow between the pollution sources and your well are the primary concerns.

After reading Part 1 of this fact sheet, fill out the assessment table in the accompanying work sheet to determine your possible risks. The information below will help you answer questions in the table.

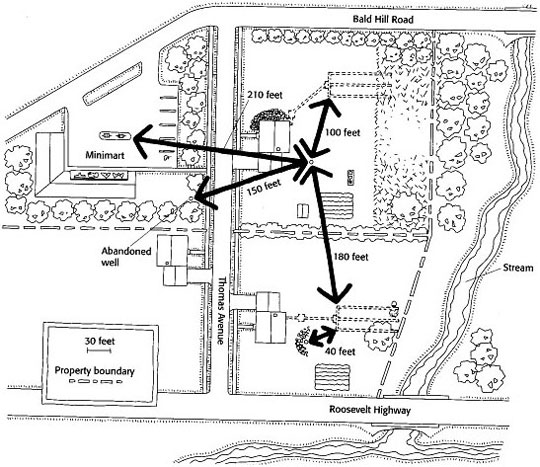

Figure 3.1

Map of homesite showing distances of pollution sources from well.

What pollution sources might reach your well?

Whether groundwater in your area is just below the surface or hundreds of feet down, the location of your well on the land surface is very important. Installing a well in a safe place takes careful planning and consideration. Where the well is located in relation to potential pollution sources is a critical factor (Figure 3.1).

When possible, locate your well where surface water (storm water runoff, for example) drains away from it. If the well is downhill from a leaking fuel storage tank, septic system or over-fertilized farm field, it runs a greater risk of becoming contaminated than does a well on the uphill side of these pollution sources.

In areas where the water table is near the surface, groundwater often flows in the same direction as surface water. Surface slope, however, is not always an indicator of groundwater flow direction.

Changing the location or depth of your well may protect your water supply, but not the groundwater itself. Any condition likely to cause groundwater contamination should be eliminated, even if your well is far removed from the potential source.

Does your well meet separation distance requirements?

Missouri requires that new wells be located a minimum distance from sources of potential pollution. Table 1 gives the minimum separation distances according to Missouri Code of State Regulations 10 CSR 23-3.010. When no distances are specified by state or local law, provide as much separation as possible between your well and any potential pollution source — at least 100 feet. Separating your well from a pollution source may reduce the chance of contamination, but it does not guarantee that the well will be safe.

Table 1. Separation Distances from Pollution or Contamination Sources in Missouri.

| Minimum distance | Potential pollution or contamination source |

|---|---|

| 10 feet |

|

| 25 feet |

|

| 50 feet |

|

| 100 feet |

|

| 300 feet |

|

| 1,000 feet |

|

Source: Division 23 — Well Installation, Chapter 3 — Water Well Construction Code; Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Missouri Geological Survey (MGS), October 2024

|

|

What's underground?

Pollution risks are greater when the water table is near the surface, because contaminants do not have far to travel.

Groundwater contamination is more likely if the soil layer is shallow (a few feet above bedrock) or if the soil is highly porous (sandy or gravelly). If bedrock below the soil is fractured — that is, if it has many cracks that allow water to seep down rapidly — then groundwater contamination is more likely.

Check with neighbors, local farmers, or well drilling companies to learn more about what's under your property. For more information on soil type, bedrock, and the water table, see Fact Sheet 1, EQM101, Part 1, Physical Characteristics of Your Homesite.

Assessment 1

Well location

Use Assessment 1, Well location, in the accompanying work sheet to rate your well location risks. For each question, indicate your risk level in the right-hand column. Although some choices may not correspond exactly to your situation, choose the response that best fits. Refer to the information above if you need help to complete the table.

Responding to risks

Your goal is to lower your risks. Turn to the action checklist in the work sheet to record the medium- and high-risk practices you identified. Use the recommendations above to help you plan actions to reduce your risks.

Part 2

Well management

Well construction and maintenance

Old or poorly designed wells increase the risk of groundwater contamination by allowing rain or melted snow to reach the water table without being filtered through soil. If a well is located in a depression or pit, or is not properly sealed and capped, surface water carrying nitrates, bacteria, pesticides and other pollutants may easily contaminate drinking water.

You wouldn't let a car go too long without a tune-up or oil change. Your well deserves the same attention. Good maintenance means keeping the well area clean and accessible, keeping pollutants as far away as possible, and having a qualified well driller or pump installer check the well periodically or when problems are suspected. When you finish reading this section, fill out the work sheet to determine risks related to your well's design or condition.

How old is your well?

Well age is an important factor in predicting the likelihood of contamination. Wells constructed more than fifty years ago are likely to be shallow and poorly constructed. Older well pumps are more likely to leak lubricating oils, or may cause lead contamination, which can get into the water.

Older wells are also more likely to have thinner casings that may be cracked or corroded. Even wells with modern casings that are 30 to 40 years old are subject to corrosion and perforation. If you have an older well, you may want to have it inspected by a qualified well driller. If you don't know how old your well is, assume it needs an inspection.

The Missouri Department of Natural Resources Missouri Geological Survey (MGS), may have information on your well. The wellhead protection act was passed in 1987. Information on wells drilled before 1987, especially for domestic wells, may be sparse, as information was turned in on a voluntary basis.

Since the law was passed, it is now a requirement for all wells drilled to be certified, and information is required to be submitted to MGS.

To search for pre-law wells, contact

Section Secretary for Groundwater Geology

Water Resources Program

Missouri Geological Survey

P.O. Box 250

Rolla, MO 65402

573-368-2190

To search for post-law wells, contact

Section Secretary, Wellhead Protection

Missouri Geological Survey

P.O. Box 250

Rolla, MO 65402

573-368-2165

To help DNR-MGS find the well data you'll need to give them a legal description (section, township, range), name of owner at the time well was drilled, who drilled the well and an estimate of drill date.

What type of well do you have?

A dug well is a large-diameter hole that is usually more than 2 feet wide and is often constructed by hand. Dug wells are usually shallow and poorly protected from surface water runoff.

Driven-point (sand-point) wells, which pose a moderate to high risk, are constructed by driving lengths of pipe into the ground. These wells are normally around 2 inches in diameter, less than 25 feet deep and can only be installed in areas with loose soils such as sand.

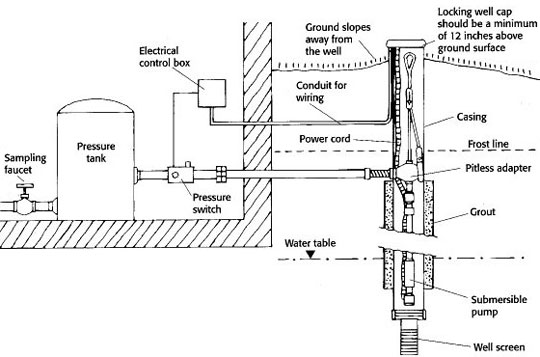

Most other wells are drilled wells, which, for residential use, are commonly 4 to 8 inches in diameter. Figure 3.2 shows a properly constructed drilled well.

Figure 3.2

A properly constructed drilled well.

Are your well casing and well cap protecting your water?

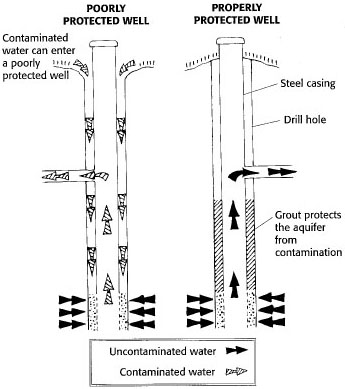

Well drillers install a steel or plastic pipe "casing" to prevent collapse of the well hole during drilling. The space between the casing and sides of the hole is a direct channel for surface water — and pollutants — to reach the water table (Figure 3.3). To seal off that channel, drillers fill the space with grout (cement or a type of clay called "bentonite").

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3

A poorly protected well versus a properly protected well.

You should visually inspect the condition of your well casing for holes or cracks. Examine the part that extends up out of the ground.

Remove the cap and inspect inside the casing using a flashlight. If you can move the casing around by pushing it, you may have a problem with your well casing's ability to keep out contaminants. Sometimes damaged casings can be detected by listening for water running down into the well when the pump is not running. If you hear water, there might be a crack in the casing, or the casing may not reach the water table. Either situation is risky.

The depth of casing required for your well depends on the depth to groundwater and the nature of the soil and bedrock below. In sand and gravel soils, well casings should extend to a depth of at least 20 feet and should reach the water table. For most wells in bedrock, the casing should extend through the weathered zone and into at least 30 feet of bedrock. A minimum of 80 feet of casing should be used for all wells.

The Missouri Well Construction Rules state, "All wells shall be watertight to such depth as may be necessary to exclude contaminants. A well shall be constructed so as to seal off formations that are likely to pose a threat to the aquifer or human health."

The casing should extend at least 12 inches above the ground surface. If there are occasional floods in your area, the casing should extend 2 feet above the highest flood level recorded for the site. The ground around the casing should slope away from the well head in all directions to prevent water from pooling around the casing.

The well cap should be firmly attached to the casing, with a vent that allows only air to enter. If your well has a vent, be sure that it faces the ground, is tightly connected to the well cap or seal, and is properly screened to keep insects out. Wiring for the pump should be secured in an electric conduit pipe.

Is your well shallow or deep?

As rain and surface water soak into the soil, they may carry pollutants down to the water table. Local geologic conditions determine how long this takes. In some places, the process happens quickly — in weeks, days or even hours. Shallow wells, which draw from groundwater nearest the land surface, are most likely to be affected by local sources of contamination.

Do you take measures to prevent backflow?

Backflow of contaminated water into your water supply can occur if your system undergoes sudden pressure loss. Pressure loss can occur if the well fails or, if you are on a public water system, if there is a line break in the system. The simplest way to guard against backflow is to leave an air gap between the water supply line and any reservoir of "dirty" water.

For example, if you are filling a swimming pool with a hose, make sure that you leave an air gap between the hose and the water in the pool. Modern toilets and washing machines have built-in air gaps.

Where an air gap cannot be maintained, a backflow prevention device such as a check valve or vacuum breaker should be installed on the water supply line. For example, if you are using a pesticide sprayer that attaches directly to a hose, a check valve should be installed on the faucet to which the hose is connected.

Inexpensive backflow prevention devices can be purchased from plumbing suppliers.

How long since your well was inspected?

Well equipment doesn't last forever. Every ten to fifteen years, your well will require inspection by a qualified well driller or pump installer. You should keep well construction details, as well as the dates and results of maintenance visits for the well and pump. It is important to keep good records so you and future owners can follow a good maintenance schedule.

Responding to risks

Your goal is to lower your risks. Turn to the action checklist in the accompanying work sheet to record the medium- and high- risk practices you identified. Use the recommendations above to help you plan actions to reduce your risks.

Assessment 2

Well construction and maintenance

Use Assessment 2 in the accompanying work sheet to rate your risks related to well construction and maintenance. For each question, indicate your risk level in the right-hand column. Although some choices may not correspond exactly to your situation, choose the response that best fits. Refer to Part 2 above if you need more information.

Part 3

Well management

Water testing and unused wells

Water testing helps you monitor water quality and identify potential risks to your health. Contaminants enter drinking water from many sources. Many contaminants can only be detected through a water test.

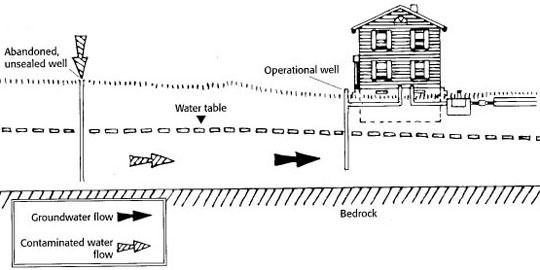

Abandoned wells, if improperly sealed, can provide a direct route for contaminants to enter groundwater. It is important to identify old or abandoned wells and determine appropriate action. When you finish reading part 3, fill out the work sheet to determine water quality risks related to water contaminants and old wells.

Figure 3.4

Abandoned wells that are not properly sealed provide a pathway for contaminants to reach groundwater.

Are there any unused, abandoned wells on your property?

Many properties have wells that are no longer used. Sites with older homes often have an abandoned, shallow well that was installed when the house was first built.

If not properly filled and sealed, these wells can provide a direct channel for waterborne pollutants to reach groundwater (figure 3.4).

In Missouri, information is available to help you close your own well. The publication Eliminating an Unnecessary Risk: Abandoned Wells and Cisterns is available from the Department of Natural Resources at 800-361-4827.

You can also hire a licensed, registered well driller or pump installer to close these wells. Effective well plugging calls for experience with well construction materials and methods, as well as knowledge of the geology of the site.

The cost to close a well will vary with well depth, well diameter, and soil/rock type. The money spent sealing a well will be a bargain compared to the potential costs of cleanup or the loss of property value if contamination occurs.

Closing an abandoned well can also reduce potential liability for injury or loss of life due to accidents.

When was your water last tested?

At a minimum, your water should be tested every year for the four most common indicators of trouble: bacteria, nitrates, pH, and total dissolved solids (TDS). If you haven't had a full-spectrum, comprehensive water test, then you don't know the characteristics of your water.

Contact your county health department to determine the availability of water testing services in your county. A more complete water analysis for a private well will tell you about its hardness, corrosiveness, and iron, sodium and chloride content. In addition, you may choose to obtain a broad-scan test of your water for other contaminants such as pesticides. A good source of information on well water quality may be your neighbors. Ask them what their tests have revealed.

What contaminants should you look for?

Test for the contaminants that might be found at your location. For example, if you have lead pipes, soldered copper joints, or brass parts in the pump, test for the presence of lead. Test for volatile organic chemicals (VOCs) if there has been a nearby use or spill of oil, liquid fuels, or solvents. Contact your county health department for information on testing for chemical contaminants.

Pesticide tests, though expensive, may be justified if your well has a high nitrate level — more than 10 milligrams per liter (mg per liter) of nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N) or 45 milligrams per liter of nitrate (NO3). Tests are also warranted if a pesticide spill has occurred near the well. Pesticides are more likely to be a problem if your well is shallow, has less than 15 feet of casing below the water table, or is located in sandy soil and is downslope from farms or golf courses where pesticides are used.

You can seek further advice on testing from your local MU Extension center or health department.

You should test your water more than once a year if

- Someone in your household is pregnant or nursing;

- There are unexplained illnesses in the family;

- Your neighbors find a dangerous contaminant in their water;

- You note a change in water taste, odor, color or clarity; or

- You have a spill or back-siphonage of chemicals or fuels into or near your well.

Water can be tested by both public and private laboratories. Once tested, keep a record of your results with your records on well construction and maintenance. This will allow you to monitor water quality over time.

Assessment 3

Water testing and unused wells

Use Assessment 3 in the work sheet to rate your risks related to water quality and unused wells. For each question, indicate your risk level in the right-hand column. Although some choices may not correspond exactly to your situation, choose the response that best fits. Refer to Part 3 above if you need more information.

For more information

Contact your local health department or MU Extension center, private testing laboratories, or the Missouri Department of Natural Resources Missouri Geological Survey at 573-368-2165.

Drilling and sealing wells

Contact pump installers, well drillers, or the Missouri Department of Natural Resources Missouri Geological Survey.

Missouri Department of Natural Resources Missouri Geological Survey Wellhead Protection Program.

Groundwater, soil type and geology

Contact your state or U.S. Geological Survey.

Drinking water quality standards

Call the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Safe Drinking Water Hotline at 800-426-4791

Contact the Missouri Farm-A-Syst/Home-A-Syst Program at: 205 Agricultural Engineering Building, Columbia, Mo. 65211; 573-882-0085.

This guide was prepared by Steve Mellis, Water Quality Associate, MU Extension, based on the Home-A-Syst chapter prepared by Bill McGowan, Agriculture/Water Quality Extension Educator, University of Delaware Cooperative Extension. Adapted from Farm-A-Syst fact sheet #1, "Reducing the Risk of Groundwater Contamination by Improving Drinking Water Well Condition," by Susan Jones, U.S. EPA Region V, Water Division, and University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension.

The Missouri Home-A-Syst series was produced with funding from the United States Department of Agriculture and was adapted for use in Missouri from the National Farm-A-Syst/Home-A-Syst Program in Cooperation with the Northeast Regional Agricultural Engineering Services (NRAES).