Dairy producers face challenges as they enter, expand or exit the dairy industry. Those entering the dairy industry often find attracting financing difficult and may find that accumulating an acceptable level of equity to get started will take several years. Expanding dairy producers are often so highly leveraged they have little margin for error, making their businesses susceptible to failure due to production or price swings. Older dairy producers face the challenges of increasing age and the desire to accumulate cash for retirement rather than reinvest in their dairies. Without a plan for succession, a smaller farm may not generate enough revenue to pay attractive wages or attract experienced, productive farm employees. The net result of the challenges faced by dairy producers is a lack of reinvestment in an entire regional dairy industry.

To guide future dairy producers through these challenges, University of Missouri faculty explored career paths that have succeeded in other regions, particularly in pasture-based dairy production. Opportunities do exist to enter the dairy industry, but these opportunities depend upon imagination, a willingness to work with others and a willingness to be proactive in creating a path for oneself.

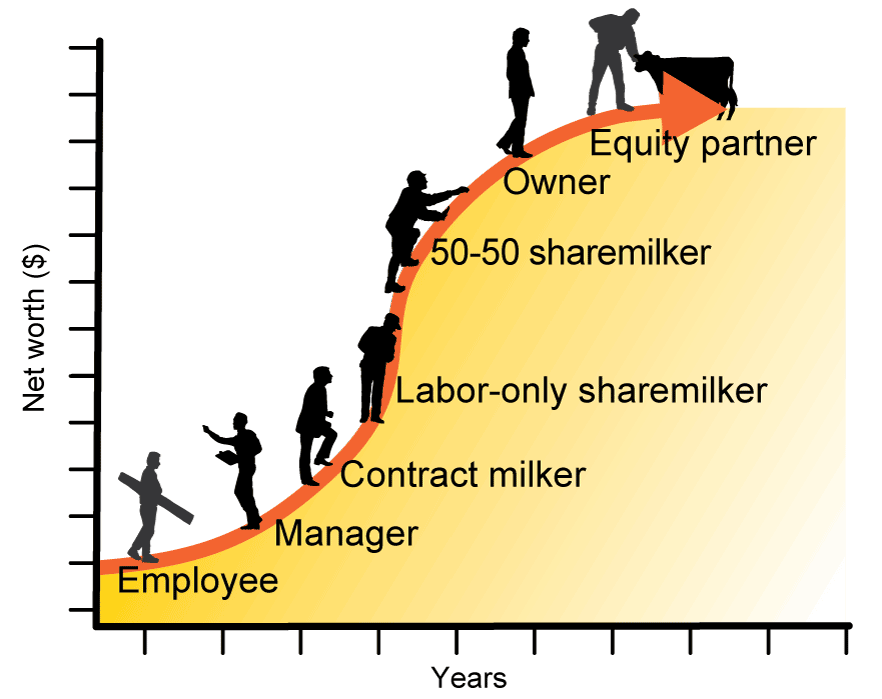

Figure 1 depicts a dairy career path from beginning as an employee to ending as a dairy owner or equity partner. Entry opportunities exist at several places along the path, depending on a person’s experience and financial situation. As individuals progress along the career path, their skills, knowledge and financial situation improve, leading to the possibility of investing in and eventually owning a dairy.

Figure 1. Dairy career path from employee to owner or equity partner.

Farm employee

Farm employees gain work experience and benefit from the knowledge of the dairy manager or owner. A person wanting to become a dairy producer should consider starting as a dairy farm employee and should let the owner or manager know of this desire.

Typically, a new employee will perform daily chores such as milking or feeding the cows. As a farm employee, a worker is expected to develop a good work ethic and learn a variety of farm skills and basic animal care techniques. As experience is gained, a good employee might be made responsible for calf rearing and assisting with cow breeding, cropping operations, grass management or other farm tasks. A farm employee with ownership aspirations should learn all aspects of the dairy operation. The knowledge and skill gained while working each segment of the dairy farm will better prepare the employee for future steps along the career path. Typically, a motivated, career-minded person will be an employee for one to four years and then move up to a herdsman, an assistant farm manager or second-in-command position on a larger dairy.

Having an employment contract between a farm owner and employee is a good business practice. The contract protects the employee and the farm owner from misunderstandings that may arise. The employment contract provides direct communications about responsibilities, expectations and concerns about the farm position. At a minimum, the contract should include the following items:

- Names of parties involved

The names specified should be the farm employee and the actual employer, not the farm manager. - Description of work duties

This description should include a majority of the responsibilities and work that will be performed under this contract and any special or different tasks required by the farm. - Expected number of work hours

The total expected hours of work stated should be as accurate as possible. The contract should also state what time and days the employee is expected to be at work, scheduled days off and pay adjustments for unplanned extra hours. Although nobody should be expected to work all the time, the employee should remember during busier seasons that additional expectations may exist. The employer and potential employee should discuss the work hour expectations thoroughly to make sure they are understood. - Wage rate or salary

This description should include pay rate, frequency and form of payments, and any other benefits, such as housing, meat or workwear. - Grievance procedure

Farms with several employees may have a grievance procedure, which is a simple explanation of how employment problems will be resolved. This procedure may outline an employee’s right to take up a grievance, the timeline, and the steps the employer will take to ensure employment problems are dealt with quickly and efficiently. It should also explain the options available to both parties if this internal procedure fails to deliver a satisfactory solution. Many farm owners feel their operations are too small for a grievance procedure and may not include this in the hiring documents. - Duration of the agreement

The contract should state the length of the agreement — a specific date range, season or year — or that it is open-ended. The employee needs to understand the length of employment to ensure time to secure subsequent employment. The employer needs to understand the contract length to ensure sufficient employees are available to perform farm duties.

An employment contract may also include these items:

- Vacation and sick leave policy

- Performance review policies and schedule

- Security and confidentiality agreement

- Employee termination process

The employee should review all hiring documents at the time of hiring so any questions and concerns can be addressed immediately. Employees who fail to completely review the documents may not fully understand job expectations and requirements. The day of hire is the time to raise issues, not days or weeks later.

Farm manager

The next step along the career path is farm manager. Although moving to a different farm with different employees, cows, facilities, systems and owners can be stressful, it can create new and revitalizing opportunities. The farm manager typically is responsible for the daily operations and decision making of the dairy. The farm manager will make a majority of the decisions concerning farm activities such as feeding, breeding, forage management and labor. The farm manager answers to the farm owner and is seldom responsible for the farm finances.

Because of the additional responsibilities, the farm manager’s salary should be substantially higher than that of farm employees. Farms may offer manager opportunities not available to other employees and often provide living quarters for the manager and his or her family, which allows them to focus on saving money so they can purchase equity in the farm, livestock, equipment or even a different dairy farm.

One of the most challenging aspects of being a manager is dealing with employees. The manager may be responsible for hiring and firing personnel and other human resource functions. Effectively handling people and the issues they bring can determine the future success of a farm. One of the most difficulty and frustrating tasks of a manager is maintaining a reasonable and fair work schedule. Sufficient employees need to be on hand to perform the necessary tasks, but employees — and managers — also need time off. The manager should be flexible with the schedule while protecting his or her own time away from the farm. Too often, managers feel like they cannot afford to be away from the farm. This can quickly lead to burnout and can adversely impact the manager’s relationship with the farm staff, family members and even the farm owners.

Farm managers are often asked to sign an employment contract. The contract should clearly explain the farm owner’s expectations of the manager. Some farms require the manager to be responsible for the operation of the entire farm, while others assign the manager specific jobs. Having the expectations clearly explained in writing helps to ensure the expectations are understood and to eliminate potential conflict. If the farm has a system to reward the manager for superior performance, the expectations and rewards should be clearly defined in the contract. These rewards might be based on milk production, cost containment or simple profitability.

If a person owns a competitive farm but is unable to manage one because of age, physical condition or another reason, hiring a farm manager might allow the person an opportunity to be in the dairy business without having to personally meet all of the physical demands of the dairy. The key to success is having a competitive farm, finding the right manager and then creating an agreement that is fair and reasonable for both the manager and the owner. Such an owner-manager relationship can create opportunities for the farm manager and provide the farm owner a dependable income stream.

Contract milkers

Contract milkers provide milking labor and management for a given price. The contract milker agreement may be a fixed-rate contract agreement where payment is based on pounds or hundredweight (cwt) of milk production. This type of agreement gives the milker an opportunity to increase income without assuming as much of the risk as an owner or sharemilker. The dairy owner bears most of the risk from fluctuations in milk production, feed costs, weather, milk prices and other production and income variables.

A contract milker may employ most of the farm milking labor and perform human resource functions such as hiring and firing milking staff. The contract milker, in return, receives a given amount of income to cover labor and management costs.

Contract milker agreements may also include an incentive for increased milk production or quality improvements and should be written so that all parties benefit from increased income.

Contract milkers have the opportunity to fine-tune their management skills under the careful eyes of an owner. This is a great training position, giving limited responsibility to the contract milker while allowing his or her management knowledge and skills to improve.

Sharemilking

Sharemilking provides a way for a dairy owner and sharemilker to share the risks, benefits and costs of running a dairy operation (Tranel, 1996). Sharemilking is a contractual agreement that involves operating a farm on behalf of the farm owner for an agreed share of the farm receipts, as opposed to a set wage for a contract milker.

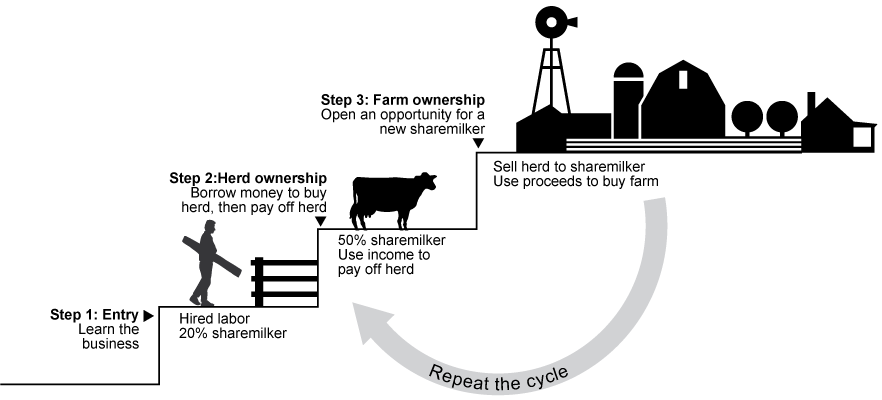

The share of the farm receipts is based on the value of each party’s contributions to the dairy operation. Figure 2 shows the sharemilking steps to farm ownership. The sharemilker is responsible for providing the labor required for harvesting the milk and other farm duties defined in the agreement. Because the sharemilker shares income and key operating expenses, the agreement has a built-in incentive to improve performance on the farm. A sharemilker agreement is a tool to allow the owner to still be involved in the farm while creating an opportunity for someone else to learn and improve his or her management skills and knowledge.

Figure 2. Sharemilking steps to ownership.

Types of sharemilking agreements

Although owners and sharemilkers can create any type of sharemilking agreement, the two typical types are labor-only and 50 percent sharemilking agreements.

In a labor-only sharemilking agreement, the owner provides the land, facilities, equipment and herd. The sharemilker provides labor for the operation. The owner retains ownership of the herd and bears more of the farm costs such as hay-making and animal health. The amount of farm work required of the sharemilker is determined by the specific agreement, with the responsibility ranging from managing the herd only to carrying out all farm work. The sharemilker shares some of the production and price risk related to the milk check. This agreement allows a dairy owner who is not physically able to run the farm to continue owning and managing the farm while giving a sharemilker an opportunity to increase his or her management skill and potential income. In labor-only agreements, the sharemilker generally pays about 20 percent of key operating expenses, such as feed and purchased forage, and receives about 20 percent of the income, depending on the responsibility and risk being taken by the sharemilker versus that being taken by the owner.

Table 1. Labor-only sharemilking agreement.

| Party | Contributions | Share of income and key operating costs |

|---|---|---|

| Sharemilker | Labor | About 20 percent |

| Dairy owner | Land, facilities, equipment and cows | About 80 percent |

Under a 50 percent sharemilking agreement (also called 50-50), the sharemilker owns the herd and the equipment needed to farm the property but does not own the milking facility. Usually, the sharemilker is responsible for the milking expenses, dairy cattle-related expenses and general farm work and maintenance. The owner is responsible for property maintenance and improvement expenses. Annual costs of fertilizer, seed and purchased feed and forage are split 50-50 between the sharemilker and owner. The percentage quoted in a 50 percent sharemilking agreement usually refers to the proportion of milk income the sharemilker receives. Although this percentage is most commonly 50 percent, it can range from 45 percent to 60 percent, depending on the situation. Under a 50-50 agreement, the sharemilker receives the agreed percentage of milk income plus the majority of income from stock sales, and the farm owner receives the remaining income. The sharemilker retains livestock ownership and can thus gain more equity and increase net worth as the number of dairy animals owned and paid for increases.

A 50 percent agreement provides an opportunity for a person on a dairy career path to maintain an existing dairy when the owner does not desire to provide the labor and management necessary for a successful operation. In this case, the owner treats the farm as an investment and wants a fair return on the assets, and the sharemilker often takes the responsibility for maintaining the existing systems, including manure management, feed and milking. The owner and sharemilker will need to negotiate about fertility maintenance, equipment, lane and other facility maintenance concerns, and to understand the financial impact of a drought, rapid price change for inputs and changes in milk production.

Table 2. Fifty percent sharemilking agreement.

| Party | Contributions | Share of income and key operating costs |

|---|---|---|

| Sharemilker | Labor, cows and equipment | About 50 percent |

| Dairy owner | Land and facilities | About 50 percent |

Sharemilking agreement concerns

Careful planning of a sharemilking agreement is important and should include creating a detailed breakdown of how each party will contribute to the agreement. MU Extension has developed a sharemilking evaluation tool (XLSX) useful in developing a reasonable agreement. A sharemilking agreement can and should be a win-win agreement for both parties. The agreement should at a minimum include the following items:

- Names of parties involved

- Terms of agreement (termination, renewal, etc.)

- Responsibilities of each party

- Capital contributions

- Sharing of income and expenses

- Number of replacements to be raised on farm

- Dispute resolution

Asset contribution values between parties can be a point of dispute in a sharemilking agreement. As capital price levels fluctuate from year to year or by depreciation, it can be challenging to determine the current market value of assets to decide the contribution levels for the sharemilker and owner.

Conflicts between owners and sharemilkers do not normally arise out of just one difference of opinion but usually stem from an accumulation of differences that eventually causes one or both parties to reach a breaking point that can result in termination of the contract.

Outside experts, such as attorneys and accountants, can be useful in reviewing or helping to develop a sharemilking agreement that works for both parties. Additionally, before entering an agreement, each party should interview the other and check the other’s background references.

Farm owner

The transition from sharemilker to owner requires capital. A 50 percent sharemilker should have equity available in his or her livestock, which together with available cash may provide the equity necessary to acquire financing for a farm.

When considering purchasing or developing a dairy farm, remember that the owner-operator is completely responsible for the success or failure of the farm and is subject to all the risks and rewards of farm ownership. Depending on owner’s finances and desired level of involvement with the farm, the owner may employ personnel who are on the dairy career path as farm employees, managers, contract milkers or sharemilkers.

Partnerships

The final stage of dairy ownership is some form of joint ownership such as a limited liability company (LLC) or S or C corporation, which will be characterized here as a partnership, regardless of legal entity form used. In a partnership agreement, a group of investors pools their resources to provide financing for a dairy farm. Typically, the group hires a farm manager, and the manager answers to the owners through a board organization. A partnership allows the owners to benefit not only from the success of their owned farm but also from the success of the equity business. The partnership also allows nondairy producers to invest in and benefit from the success of a dairy farm.

A partnership enables the partners to pool their capital into a single operation or company. Some groups require a large investment and others a small minimum investment. The larger the group, the more complex the operational documents. Size may also impact the organizational business form and how the business operates, with a large group requiring several levels of administration.

One strategy in forming a successful partnership is to involve people with different skills. One investor might excel at cow health and management, another at forage management and a third might know finances. By bringing this group together as an equity partnership, the operation can benefit from each unique skill set. However, the groups must be cautious not to send mixed signals to the farm manager, which can cause confusion and hinder the farm’s success. The board is to provide direction and oversight not daily management; the manager must be allowed to make the day-to-day decisions of the farm.

Making the farm manager one of the equity partners has advantages. The managing partner benefits from ownership with a reduced level of capital input, shares some of the ownership risk and can benefit from exposure to the thoughts, skills and knowledge of the other owners. Again, however, caution must be exercised concerning the day-to-day management of the farm; the agreement must fully describe the responsibilities of the managing partner and the other owners, and the decision process that affects all the financially involved parties.

A retiring farmer can benefit from forming a partnership with either existing farmers or persons newer to the industry. The skills and knowledge of an experienced, retiring producer can be useful in a new dairy operation, and a partnership is a great way for a retiree to remain involved in the business without having to meet the physical demands of running a dairy.

Ownership structure and operational agreements are key to the success of a partnership. The farm’s day-to-day operations — such as who makes decisions, how decisions are made and how the manager is accountable to the owners — must be considered when creating a partnership. Entrance and exit strategies are also important for the success of the business because they allow for additional partners to be brought into the business and for a smooth transition between generations.

A solid understanding of the basic partnership model is important, but hiring the right legal and financial advisors is crucial to the overall operation of the business. Partnerships need to be well-constructed, and considerable time and effort may be required to organize and complete all of the legal documents. Due diligence is a necessity and can help make the business successful. Good relationships between partners and a common goal for the company are keys to success. A shareholders’ agreement is recommended to ensure that the expected outcomes for the business, authority of the farm manager and owners, and responsibility and expectations of the shareholders are identified and well-explained.

Dairy career path

Table 3 lays out a potential path that shows steps and progression as a dairy producer gains experience and equity.

Table 3. Potential dairy career path.

| Age | Action plan |

|---|---|

| Early 20s | Train at college and/or work on a good dairy farm as a farm employee, calf raiser, farm assistant, herd and/or manager. |

| Mid-20s to early 30s | Move into management position, milk an owner’s herd for a percentage of the milk check (labor-only sharemilker); work to accumulate own milking herd. |

| 30s | Own cattle; farm under a 50-50 sharemilking agreement, accumulating additional cattle and cash. |

| Late 30s to early 40s | Sell some of the accumulated cattle to generate a down payment for a small farm. |

| 40s to early 50s | Sell small farm and/or buy larger farm. |

| Mid-50s and up | As farm owner, enter into agreement with contract milker or sharemilker and reduce management and labor responsibilities. May also invest in a partnership. |

Source

University of Wisconsin, 1998.

References

- Tranel, Larry F. 1996. “Sharemilking in the Midwest.” University of Wisconsin-Extension, A3670.

- University of Wisconsin-Madison. 1998. “New Zealand’s dairy career path: Could it work in Wisconsin?” Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems, Research Brief 33.