Bats are unique and interesting animals. Because of their nocturnal nature and widespread misconceptions about them, they are the subject of myths and folklore that make them one of the most mysterious and misunderstood mammals. The presence of a bat in a house causes more alarm than does any other wildlife species.

These fears are unwarranted. Contrary to what you may have heard:

- Very few bats become rabid (less than half of 1 percent).

- Bat droppings in buildings usually are not a source of histoplasmosis.

- Bats are not filthy and will not infest homes with dangerous parasites.

- Bats are not aggressive and will not attack people or pets.

- Missouri bats do not feed on blood. (Vampire bats, which do feed on blood, live in Latin America.)

Like all wildlife, bats have their place in the natural world and should not be killed indiscriminately. This publication provides some answers for Missouri homeowners on managing bat problems. It also provides information on how to attract bats to your property.

All wildlife species are protected by Missouri law; it is illegal to kill any bat in Missouri unless it is damaging your property. Two Missouri bats are classified by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as endangered species and need protection to survive environmental disturbances caused by humans. Nonlethal controls are recommended for managing bat problems in a house.

Big brown bat.

Big brown bat.

Missouri bats

Bats belong to the order Chiroptera, which means "hand-wing." They are the only mammals capable of true flight. In number of species, Chiroptera is the second largest group of mammals in the world. Only the order Rodentia (rodents) contains more species.

Fourteen species of bats are commonly found in Missouri, but they are most numerous in the dense forests and abundant caves of the Ozarks. Six of these species spend at least part of the year roosting in caves. The others roost mainly in trees. Only three species regularly roost in buildings (big brown bat, little brown bat, evening bat).

- The little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) is a brown, mouse-sized bat that occurs throughout Missouri. It hibernates in small numbers in Ozark caves during winter. In summer, it sometimes takes up residence in attics and buildings, where it rarely causes damage.

- The northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis) is a small bat much like the little brown bat, except that the ears extend beyond the nose when flattened against the head. These bats are rarely seen. They usually roost in crevices of caves. Long-eared bats are classified as endangered in Missouri and Federally threatened.

- The big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) is a large bat, perhaps twice the size of the little brown bat, but still weighs only half an ounce. This species lives throughout Missouri and roosts by itself or in small groups in caves. Big brown bats commonly roost in buildings, where they sometimes hibernate.

- The gray bat (Myotis grisescens) is an endangered species. It is a medium-sized, grayish bat that is usually found in large, active clusters. Gray bats use caves as roost sites year-round. They roost in large numbers; roosting caves contain huge amounts of bat guano (manure). Typically, they use many caves during the summer and only a few during the winter.

- The Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) also is an endangered species. It is a small, pinkish brown bat. In Missouri, the Indiana bat spends the winter hibernating in caves in the Missouri Ozarks. Indiana bats form large, dense clusters during the winter but do not deposit piles of guano under these roosts. They disperse across the state during the summer.

- The red bat (Lasiurus borealis) is smaller than the big brown bat. Its fur is rusty red, washed with white. It roosts among leaves of trees and is seen in abundance statewide, often foraging around large lights in towns. It is solitary. Many will migrate in winter. In southern Missouri, some red bats remain during the winter and may emerge from their roosts on warm winter days to catch insects.

- The hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus) is larger than a big brown bat and about twice the weight (one ounce). It is the largest bat in Missouri. Its color is a rich, dark brown, overcast with grayish white. It roosts among the leaves of trees, but is less common than the red bat. It is solitary and migrates.

- The evening bat (Nycticeius humeralis) is present in Missouri during the spring, summer and early fall. It migrates south in winter. It roosts in buildings in summer.

- Rafinesque’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus rafinesquii), also known as the Southeastern big-eared bat, is relatively uncommon in the state and throughout its range. The species primarily roosts in trees and its habitat is associated with large areas of mature forests, such as those in southern Missouri.

- The Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii) is a medium sized bat with long, flexible ears and noticeable lumps on each side of its snout. The species can be found in the state during migration periods and commonly roost in caves during the year.

- Silver-haired bats (Lasionycteris noctivagans), inhabit forests throughout its range and during periods of migration. They roost in tree cavities or in bark crevices. In Missouri, reproduction occurs in the northern region of the state and individuals may overwinter in buildings, homes or in other structures.

- The Tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus), formally known as the eastern pipistrelle bat, is the smallest bat species in the eastern and midwestern United States. It is Missouri's smallest cave bat (only 3 inches long) and is a pale yellowish brown color. It is rarely found in buildings, but instead prefers caves and rock crevices. As with many bat species, they mate in the fall before hibernation with young born the next spring. Young are born helpless, though rapidly develop, flying and foraging for themselves by four weeks old. It has a relatively long lifespan, and can live nearly fifteen years.

- The eastern small-footed bat (Myotis leibii) is among the smallest of bat species and is known for its small feet and black face-mask. This species is rare throughout its wide range throughout North America, however, they may be locally abundant where suitable habitat exists.

- The southeastern myotis (Myotis austroriparius), is another very small bat species that can be found throughout the southern United States as well as in portions of Missouri at various times of the year.

More detailed information on species of Missouri bats can be found at Missouri Department of Conservation website.

Benefits of bats

Missouri bats consume literally tons of insects in our state each year and are one of our best allies in controlling insect numbers. A single little brown bat (one of the common house-dwelling bats) may eat 600 mosquitoes in an hour. Bats are the only major predator for night-flying insects.

In other parts of the world, bats pollinate and disperse seeds for many tropical plants. Wild stocks of bananas, avocados, dates, figs, peaches, mangoes, cloves and cashews are pollinated by bats.

Bats have contributed to medical research in birth control and artificial insemination techniques, navigational aids for the blind, vaccines and drugs, and new surgical techniques. Without bats, we would suffer great economic losses and our quality of life would be reduced.

Biology and habits

Like other mammals, bats are warm-blooded and furry and nurse their young. They are not blind but navigate and detect food by a sophisticated system called echolocation. Echolocation is unique to bats and some species of dolphins and whales. It is similar to common sonar, in which a sound is emitted by the bat and bounces off insects or objects and returns to the bat's ears. Echolocation enables bats to catch insects in flight. Most of the high-frequency sounds emitted by bats for echolocation are inaudible to humans, although bats also produce sounds that humans can hear.

Bats naturally roost in the leaves of trees, under loose tree bark or in caves during the day, but some species prefer to roost in or around structures built by humans. Depending on the species, bats become active during the twilight hours or shortly after dark. When bats leave the roost, they normally fly to a source of water before feeding. Some species feed occasionally throughout the night, but most feed around sundown and then again before daylight.

Missouri bats mate in the fall and early winter as they gather in caves in which they will hibernate. The females hold sperm in their reproductive tracts until spring, when fertilization occurs. Pregnant females then move from their winter hibernating sites (called hibernacula) to maternity sites or nursery colonies.

Birth occurs from mid-May through mid-July. Most species of bats give birth to only one or two young, six to eight weeks after fertilization. This is an exceptionally low reproductive rate for a small mammal. Thus, their populations are vulnerable and require a long time to recover from setbacks. Most bats breed during their first year of life; a few may survive for 30 years.

Young bats grow rapidly, and most are capable of flight four to five weeks after birth. They are weaned one to two weeks later. While females are attending to the young in nursery colonies, males congregate in separate groups called bachelor colonies. Groups of bats found in buildings in Missouri usually are nursery colonies.

Dropping fall temperatures force many Missouri bats to migrate. Their migrations usually are less than 300 miles. Bats look for a cave or other hibernating site with an optimum temperature varying from 41 to 58 degrees. Big brown bats, commonly found in buildings, can survive subzero temperatures and may hibernate in walls, attics, cliff faces and rock shelters.

Fall migrations usually begin in August. The bats return in April and May. Bats have amazing homing abilities, returning to the same summer and winter quarters every year.

Diseases

Harboring bats in homes and schools should be discouraged because on rare occasions a bat may develop paralytic rabies and fall within reach of children and pets. There is also evidence of rabies virus variants in bats. Rabies is the most important public health hazard associated with bats. Since the transmission of rabies by a bat was first reported in 1953, rabid insectivorous bats have caused an average of 700 to 800 cases annually.

Bats will bite in self-defense if handled. Wear leather gloves and avoid direct contact with the bats if at all possible. If you are bitten, take the bat to county or state health officials and consult a physician.

Histoplasmosis is a disease humans can contract from bat guano. This airborne disease, caused by a microscopic soil fungus sometimes present in association with bat droppings, affects the lungs with symptoms similar to influenza. To avoid contracting histoplasmosis, wear a respirator or approved dust mask while cleaning bat droppings in an attic or other structure.

Bats generally avoid contact with humans. However, they may be infected with pathogens without showing obvious signs. Be advised not to handle any bat or keep one as a pet.

White Nose Syndrome is an exotic disease that impacts bat populations across their range. This disease, introduced from Europe, has caused massive die offs in bat populations as it moved from the northeastern United States to the west and south. It is a fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) that is capable of infecting a large percentage of bat species and is a major concern for those species that overwinter and roost in caves. The disease spreads through roosts and weakens the animals. The animals then become active early from their winter hibernation. The bat, which is already in a weakened state is not able to find enough food to survive and starves to death. The fungus was first found in caves in New York state in 2007 and was confirmed to have entered Missouri in early 2012 and has since infected several bat colonies across the state.

Controlling bat problems

Most of the time, bats are unlikely to become a nuisance in homes or other structures. Many species are never encountered by most humans. Many of the more common species go unnoticed by everyone except bat enthusiasts. Usually, only big brown and little brown bats ever take up residence in buildings.

Like many other animals, bats create problems when they come into conflict with humans. When this happens, control measures, not necessarily lethal, should be taken. The presence of bats in the area or neighborhood is not detrimental. In fact, bats provide many more benefits than most people realize.

Control measures must provide a long-term solution to the problem. Many short-term control measures are illegal and hazardous to both bats and humans.

For more detailed information on controlling nuisance bats, refer to the Center for Wildlife Damage Management bats publication.

Inspecting for bats

The first step in a bat control program is to make sure that the building is in fact infested with bats. Solitary bats will enter a building through an open window or door while searching for food. Bats may be seen flying around a porch light, chasing the insects attracted to the light. Squeaking, scratching and thumping sounds heard in walls and attics may be other pests such as rats or mice. Rustling and twittering sounds coming from an old chimney may be caused by chimney swifts.

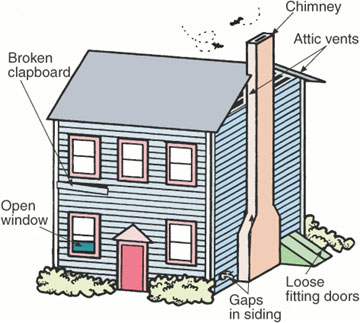

Figure 1

Figure 1

Bats can enter homes through a number of locations.

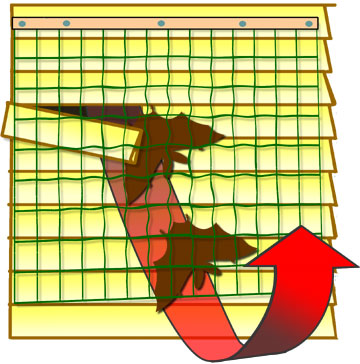

Figure 2

Figure 2

Bats can enter an attic through small openings.

Excluding bats from a dwelling is the only long-term control method. A simple inspection of the outside of the building can be made to determine whether bats are living in it (Figure 1). Bats usually enter a building at the roof/wall joint, under loose fascial boards, or through broken attic vents or other cracks resulting from building deterioration. Bats can crawl through openings as small as half an inch wide (Figure 2).

The bat inspection should be started about 30 minutes before dusk. Station enough people around the building so that the entire roof and wall area can be kept under constant observation. If bats are present, they will start leaving the building about dusk; the last bat should come out of the building within one hour of the first bat. All bat exit and entrance points should be noted, as well as the number of bats. This procedure may take several evenings to accomplish, but it is important to identify all bat holes.

Bat-proofing buildings

The only method to rid a building of bats permanently is to bat-proof the structure. Merely repelling bats will not provide long-term control.

The best time of the year to bat-proof a house is between November and March, after the bats have left and before they return in the early spring. Exclusion carried out between mid-May and mid-August will result in young bats being trapped inside, where they will die and create an odor problem.

If only one exit/entry hole is found in the course of the inspection, it can be plugged as soon as the last bat leaves the roost (hence the reason for counting the bats). If several holes are identified, all but one of them should be plugged during the daytime. Wait a day or two to give the bats a chance to get used to using the last opening, then plug it as soon as the last bat has left in the evening. If all holes can be safely plugged at night, then it is not necessary to wait the extra day or two.

An excellent way to plug an entrance hole is to install a bat-proofing valve. This device, which consists of a rigid base tube with a pliable outer sleeve attached, is placed over the entrance hole, allowing bats to exit the dwelling but not to re-enter.

Homeowners can make their own simple bat-excluding device by using 1/2-inch plastic bird netting available at local garden or hardware stores. Cut a piece of netting several feet larger than the opening so that at least two feet of material hang on both sides of and below the entry hole. Hang the netting during the day several inches above the entry hole. The top may be stapled, taped, or nailed to the building, but the bottom must be allowed to hang free (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Figure 3

Using bird netting, above, to exclude bats from a house.

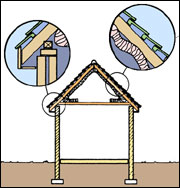

Figure 4

Figure 4

A properly insulated roof will keep bats out.

Bats will not gnaw or claw their way into a building as rats and mice will. Therefore, almost anything can be used as a temporary seal — fiberglass insulation, rags, oakum, steel wool, etc. Permanent bat-proofing requires materials such as sheet metal, 1/4-inch hardware cloth or plastic netting, plywood, caulking compound or aerosol foam insulation (Figure 4). On large buildings or those with many openings, exclusion can be expensive and labor intensive.

Bat repellents

There may be times when, for various reasons, exclusion is not possible or the bats need to be forced out of the building before exclusion methods are used.

- Naphthalene – these crystals or flakes are the only repellents registered by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for indoor use to repel bats. They are to be applied in attics or between walls. While many chemical aromatics and irritants have been proposed and tested for bat repellency, efficacy has been very limited thus far and this includes the use of naphthalene. In most cases, its use is not practical and not recommended.

- Bright lights installed in unoccupied attic to illuminate roosting sites may repel bats. The key is to make sure that all roost sites are illuminated. Large attics may require several 100- to 150-watt bulbs. This method is cleaner and safer than other methods.

- Drafts from carefully directed electric fans have successfully repelled bats.

- Ultrahigh-frequency sounds, despite the claims made by some manufacturers of ultrasonic devices, do not appear to be effective against bats.

- Toxicants are not available for the homeowner or commercial pest control applicator for controlling bats.

Controlling the occasional bat

On occasion, one or two bats may get into a home and fly around. Often it may be a big brown bat that entered accidentally through an open window, door or fireplace. When this happens, there is no need to panic, for it will not attack even if it is chased.

The bat usually will find its way back outdoors by following fresh air movements. Leave windows or doors open to help it escape. Turn off all lights; if any are left on, the bat may seek refuge behind wall hangings or drapes. If a bat refuses to leave, it can be caught with a net, coffee can or gloved hand and released outside. If it remains into the daytime, look for it behind curtains or bookshelves or in a high place. Grasp it with a gloved hand or put it in a container and release it outside.

Providing an alternative roost

Bat-proofing has two potential drawbacks. One is that exclusion can be stressful for a maternity colony. When prevented from using their usual roost, the bats may move into a nearby building, where they may be expelled again, or even exterminated. Also, research has shown that displaced colonies will not relocate into buildings that already house other maternity colonies. In other words, an excluded colony cannot just move down the road into a barn or church that already has bats. If a displaced colony cannot find a new roost, it may leave the area. In fact, researchers have found that expelling bat colonies can contribute to serious declines in local bat populations.

A second drawback is that homeowners may find it difficult to bat-proof their home completely. Bats can crawl through cracks as small as 1/2 by 1-1/4 inches, so persistent bats may find a way to reenter their former roost.

Bat boxes can solve both of these problems because they provide alternative roosting sites for maternity colonies. When constructed properly, bat boxes can serve as suitable places for females to raise their pups. With bat boxes, the bats get a safe roosting site outside the home, while homeowners benefit from the bats' control of insects.

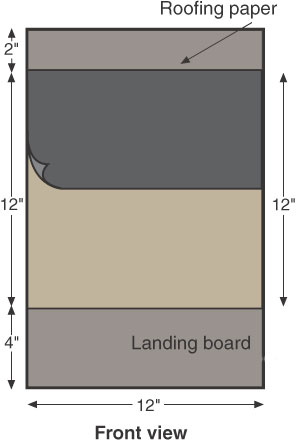

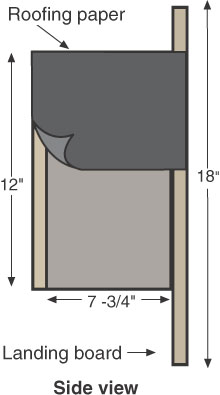

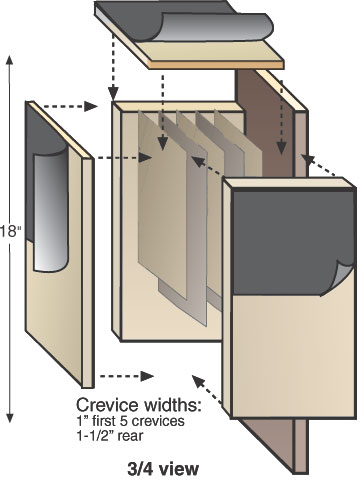

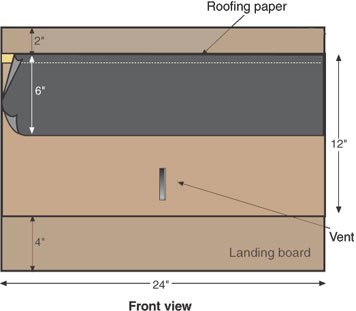

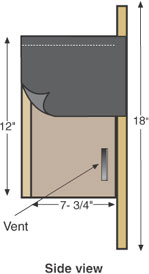

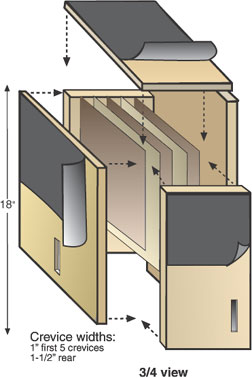

Figures 5 and 6 show two plans for building a bat house. A handsaw, hammer and staple gun are the only tools required for the beginner's bat house (Figure 5). This house can accommodate 50 or more bats.The small nursery house (Figure 6) can house a colony of 150 bats.

Figure 5

Figure 5

Beginner's bat house.

Beginner's bat house (12" x 12" x 8")

This bat box is useful when attracting bats to an area. It may be accepted by male bats or nonreproductive females. It is not large enough for most bat colonies.

Parts list

- Front

11-1/4" x 12", 3/4" exterior plywood or board - Back

18" x 12", 3/4" exterior plywood or board - Sides

11-1/4" x 7-3/4", 3/4" exterior plywood or board - Top

8-1/2" x 12", 3/4" exterior plywood or board - Baffles

1/4" lightweight plywood

3 - 10" x 10-1/2" (slightly wider if using routed grooves)

2 - 11" x 10-1/2" - Spacer strips

- 10 - 1" x 10" board strips

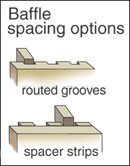

Construction (same for both houses)

- After cutting out pieces, use a knive or saw to roughen interior surfaces with horizontal scratches or grooves 1/4" to 1/2" apart.

If you use a router to cut grooves for baffles, cut 1/4" grooves into side pieces at 1" intervals.

If you use a router to cut grooves for baffles, cut 1/4" grooves into side pieces at 1" intervals.- Otherwise, attach two spacer strips to inside of front piece with nails or screws. Attach baffles and spacers alternately, making sure that baffles and strips fit tightly against the sides of the box when it is assembled.

- Assemble box as shown, using galvanized finishing nails or exterior-grade screws. Do not use wood glue. Caulk joints.

- Apply latex paint or stain to exterior of box. Do not paint or stain the interior.

- Staple roofing paper onto the top, front and sides of the house, extending it about 6 inches down from the top. This will create an important temperature difference in the box between the top and the bottom.

Figure 6

Figure 6

A small nursery bat house.

Small nursery house (12" x 24" x 8")

This bat box is suitable for small to medium-size summer maternity colonies. It should be installed in the spring.

Parts list

- Front

11-1/4" x 24", 3/4" exterior plywood or board - Back

18" x 24", 3/4" exterior plywood or board - Sides

11-1/4" x 7-3/4", 3/4" exterior plywood or board - Top

8-1/2" x 24", 3/4" exterior plywood or board - Baffles

1/4" lightweight plywood

3 - 10"x 22-1/2" (slightly wider if using routed grooves)

2 - 11" x 22-1/2" - Spacer strips

10 - 1" x 10" board strips

Not every bat house will be used. Bats are particular about the design and location of their living quarters. Bat nurseries should have a stable temperature of 80 to 110 degrees, depending on the species. Thus, the house should be made as airtight as possible. Seal all external joints with caulk to prevent heat loss.

Bats are sensitive to chemicals. Do not use treated wood and do not paint or varnish the interior of the house. To make it easier for the bats to secure a good foothold use rough lumber and place the rough sides inward. You may also cut 1/16-inch grooves to help the bats climb and roost. The roosting partitions can be covered with fiberglass insect screening or 1/4-inch hardware cloth to help young bats secure a footing.

Western red cedar is the recommended construction material because it withstands outdoor exposure. Houses also can be built of redwood or cypress. However, construction can be simplified by using exterior plywood.

To help ensure constant temperatures in the bat house, orient the house to receive maximum sunlight, particularly during the early morning. Houses will remain warmer if they are facing south. Europeans sometimes mount four houses in a group, each facing a different direction to provide a range of temperatures for the bats. You may paint the house a dark brown or black using a flat, latex paint to increase heat absorption.

Bat houses should be erected 10 to 15 feet above the ground. They should be protected from the prevailing (north and west) winds. Never place a house where the entrance is obstructed by tree limbs or vegetation. An excellent site for a house is on an old building. Bat houses placed within 1/4 mile of a permanent water source also are more likely to attract bats.

Bats typically will not occupy a house right away. Many bat houses are not used the first year they are erected, and some may never be used. However, by ensuring the house is correctly built and properly located, most bat houses will eventually be used.

An excellent alternative to building your own bat house is to buy a ready-built one from Bat Conservation International, P.O. Box 162603, Austin, Texas 78716. A portion of the purchase price goes directly to conserving bats and bat habitats. Access the organization's website for more information on bats and bat houses.

For additional information, contact your local MU Extension center. The Missouri Department of Conservation also is an excellent source of information on managing Missouri's bats.