Azaleas and rhododendrons are shrubs for all seasons. In winter some stand out with large evergreen leaves. In spring the flowers are showy (Figure 1); throughout the summer and fall the leaves add a pleasing, deep green color to the garden. Some deciduous azaleas add bright fall color before the leaves drop.

Figure 1

Figure 1

The spectacular spring flowers of azaleas and rhododendrons make them popular garden shrubs.

Although all azaleas and rhododendrons are classified in the plant genus Rhododendron by plant taxonomists, the name "azalea" is commonly used for native deciduous species and some evergreen Asian types. In contrast, "rhododendron" is used to designate those species that have large, evergreen, leathery leaves. No sharp division can be made between the two, and it is always correct to call any of them rhododendrons.

The terms azalea and rhododendron are used as they commonly apply. Whatever name is used, the culture required for all these plants is very similar. The same cultural practices may also be applied to blueberries, Pieris, heather, holly and other plants that prefer organic, acid soils.

Location

Most azaleas and rhododendrons are at their best in fairly mild, humid climates. Most of Missouri does not have their preferred climate, so selecting a good site is very important.

Slope

A site sloping to the north or east is usually best, because it is protected from drying south and west winds. Here they are less subjected to rapid temperature changes in late fall or early spring.

Wind

Always plant azaleas and rhododendrons where they get wind protection. Buildings and slopes provide good barriers. Evergreen shrubs or trees such as pine, juniper or spruce planted to the south or west of rhododendrons protect them and make good backgrounds for showing off the flowers.

Plants not given protection from the wind often develop leaf scorch or splitting of the bark on the stems. Avoid corners of buildings where wind tends to be stronger.

Shade

Many people think of azaleas and rhododendrons as shade lovers. Yet dense shade is not satisfactory. Filtered sunlight is ideal, but morning sunlight with shade after 1 p.m. is satisfactory. Plants may survive continuous shade if trees have branches pruned high. Protection from afternoon sun may also be given by fences, shrubbery or screens.

Some deciduous azaleas are less sensitive to full sun and should be used if the location is not suitable for evergreen types. However, in full sun the delicate flower shades will bleach quickly even though the plants may grow well.

Soil and its preparation

Proper placement alone is not enough. Azaleas and rhododendrons must have soil that is prepared carefully and thoroughly. Don't expect good results from plants set in existing soil in most areas. Roots of azaleas and rhododendrons are very delicate and unable to penetrate heavy or rocky soils.

Drainage

Because the delicate roots of azaleas and rhododendrons are easily destroyed, excellent drainage is important. To test drainage, dig a hole 6 inches deep in the bed and fill it with water. If the water has not drained from the hole in four hours, install drainage tile to carry away excess water, or build raised beds.

Starting the bed

Planting azaleas and rhododendrons in groups rather than individually permits more efficient use of prepared soil. Don't place the bed close to shallow-rooted trees such as maple, ash or elm. Feeder roots from these species rapidly move into improved soil and compete for water and plant food.

For best results, dig out the bed 18 inches deep and at least 30 inches wide. Plants should be spaced 3 to 4 feet apart and at least 18 inches from the edge of the bed.

If drainage is poor, build a raised bed at least a foot above ground level.

Soil acidity

Azaleas and rhododendrons must have an acid soil. Most of them thrive best at a soil pH between 5.0 and 5.5. In Missouri, most native soils have an acid reaction. However, alluvial or river bottom soils may have a more alkaline reaction and need to be made more acid to grow azaleas and rhododendrons well.

Soils previously limed heavily for a garden or other crops in the past may need the pH lowered. Mortar or similar building materials mixed into the soil close to foundations may increase pH (lower acidity). When the pH is unknown, take a soil sample to your local MU Extension center for testing.

Correcting pH

Soil for rhododendrons may be made more acid by applying agricultural sulfur or ferrous (iron) sulfate. The amount of change may vary with different soil types. Well-amended soils with a pH above 5.5 may require either iron sulfate or agricultural sulfur to lower the soil pH (make the soil more acid) by about one unit. See Table 1 for the amounts of these products to use depending on soil type and initial pH. These high sulfur amendment levels should be used only when digging a bed deeply to incorporate the materials thoroughly. For a gradual pH change in beds with existing plants that cannot be tilled, see the section (below) on iron chlorosis.

Soils that are too acid (below pH 4.5) may easily be made less acid by adding ground limestone.

Table 1

Soil amendments needed to lower loamy soil pH to 5.5

| Initial pH | Sulfur (pounds per 100 square) | Iron sulfate (pounds per 100 square foot) |

|---|---|---|

| 7.5 | 5.0 | 11.5 |

| 7.0 | 3.5 | 9.0 |

| 6.5 | 1.5 | 3.5 |

Note

Clay soils will require heavier applications of pH-lowering amendment; sandy soils, less amendment.

Mixing the soil

A large amount of organic matter is necessary for good growth of rhododendrons and azaleas. In clay soils, a mixture of 50 percent ground pine bark, or leaf mold from pine or oak leaves, 25 percent coarse sand and 25 percent topsoil could be used. Avoid using a large amount of peat, especially for rhododendrons, because peat-amended soil may hold excessive moisture during wet conditions in winter and spring. If the native soil is sandy, use 50 percent soil and 50 percent organic material.

When digging the bed, discard any heavy, tight subsoil and save the topsoil. Bring in additional good-quality topsoil if needed. Combine the topsoil, sand, organic material and sulfur (if necessary); mix thoroughly, and replace into the bed. Fill the bed area 4 to 6 inches higher than the surrounding soil to allow for settling.

If possible, the bed should be prepared several months before the plants are to be set out. Since it will take some time for the pH to change, check the soil pH about a year later to see if the adjustment was correct.

Planting

Setting the plants

Most rhododendrons and azaleas are purchased with soil around the roots either in containers or "balled and burlapped." Dig the hole in the prepared bed slightly larger but no deeper than the ball or container. Set the ball so it is 2 inches higher than the surrounding soil. Never plant azaleas or rhododendrons so deeply that the plant stem is covered deeper than it had been growing in the nursery. Planting too shallow is better than too deep. Soak well after planting and firm soil around the ball.

Mulch

Most azaleas and rhododendrons are shallow rooted and need a heavy layer of mulch to conserve moisture around the roots and to minimize winter injury. Coarse materials such as partly decomposed oak leaves or pine needles are ideal. Oak shavings, hardwood chips or aged sawdust and sphagnum peatmoss may also be used satisfactorily. Use a mulch of sawdust or hardwood chips about 2 inches deep. A mulch of oak leaves should be 4 to 6 inches deep.

Keep the mulch around the plants at all seasons of the year, but don't allow it to be too high on the plant stems during the summer and fall. In winter pile it higher to help prevent winter leaf scorch or bark splitting on the stems.

Fertilization

There is little need for fertilizing at planting time. A light application of a fertilizer formulated for acid-loving plants may be added to the surface, according to the directions on the package, before the mulch is applied.

Other planting methods

Single plants. To prepare for a single specimen, dig a planting hole about 30 inches wide but no deeper than the root ball of the specimen to be planted. This will accommodate the average-sized rhododendron plant purchased at the nursery. Single azalea plants will not need a hole quite as large. Clay in the bottom of the hole should be broken up as much as possible. While digging, save and use only the topsoil as described for bed preparation. Prepare the soil mixture as described above and fill the hole. Make sure that the fill and plant are at least 2 to 3 inches above grade. Water and mulch as previously described.

Raised beds

In some soils or locations, raised beds may be the only way to provide adequate drainage. They should be raised at least 12 inches above the normal soil grade. Instructions for making raised beds are given in MU Extension publication G6985, Raised-Bed Gardening.

Maintaining the planting

Rhododendrons and azaleas require little care once they are properly established. A good heavy mulch will keep down weeds. No cultivation should be done because the shallow, fine roots are easily damaged.

Fertilization

Avoid using general garden fertilizers for rhododendrons, azaleas and other acid-loving plants. Use those specially formulated for acid-loving plants and follow directions. Fertilizers supplying nitrogen in the ammonium form are best.

Rhododendrons and azaleas grow well naturally at relatively low nutrient levels. Therefore, fertilization should be done carefully, or the fine, delicate roots close to the soil surface will be damaged. A fertilizer analysis similar to 6-10-4 applied at 2 pounds per 100 square feet to the soil surface is usually adequate. Cottonseed meal is also a good fertilizer.

Fertilizing should be done in May, but do not fertilize after July 1. Late summer fertilization may force out tender fall growth that will be killed in the winter.

Acidity

Soil acidity must be maintained to ensure good growth. If the soil pH is above 5.5, apply iron sulfate or agricultural sulfur to the surface. The amount to apply will depend on the existing pH, but in all cases apply only a small amount at any one time.

Mulch

The thickness of the mulch must be maintained, but should not be excessive, as previously recommended. As the old mulch decomposes, add new mulch. This is best done in the late fall. Mulch should be moved away from direct contact with stems in early fall to allow hardening during the onset of cold weather. Replace and replenish mulch before a hard freeze. If wood chips, chopped bark or only partially decomposed sawdust are used, fertilize with about one-half pound of ammonium sulfate for each bushel of material used. The fertilizer is best applied in the spring.

Watering

Many rhododendrons have been killed by overwatering in sites where drainage was poor. If the soil is moist but the plant still wilts, mist over the plant lightly to increase humidity. This practice is especially important for newly planted evergreen species. Avoid excessive irrigation in fall. Plants kept dry in September will tend to harden off and be better prepared for the winter. If the fall has been excessively dry, watering should be done after the first killing frost. At that time watering will not reduce winter hardiness but will prepare the plant for winter. The soil should be thoroughly moist before cold weather sets in. The best time for fall watering is around Thanksgiving.

Pruning

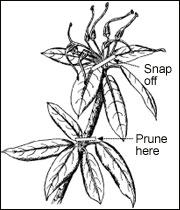

There is little need for pruning azaleas and rhododendrons. If growth becomes excessive, reduce the size with light pruning. Details are given in MU Extension publication G6870, Pruning Ornamental Shrubs, in the section on broad-leaved evergreens. It is important to remove the flower clusters on rhododendrons as soon as flowering is complete (Figure 2), although this practice is not necessary on most azaleas. Failure to do this will reduce flowering the following year. Break out only the dead flower cluster, being careful not to damage the young buds clustered at its base.

Azaleas sometimes branch poorly and form a loose, open shrub. Plant form can be improved by pinching out the soft, new shoots of vigorous-growing plants. Do not pinch after July because flower buds will not have time to develop for the following year.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Snap off flower cluster as soon as petals collapse. For more severe pruning, cut back to whorl of leaves.

Winter protection

The two winter enemies of evergreen rhododendrons and azaleas are sun and cold wind. If hardy types are selected and proper locations are chosen, little or no winter protection is needed. If existing varieties show winter damage, provide some protection. Don't be alarmed when leaves curl and droop on cold days; that is normal.

Discarded Christmas trees may be used to protect plants. Branches can be anchored in the ground to shield the rhododendron from wind and sun. Screens may be built of burlap or other materials to provide shade and windbreak. Protection must remain loose and airy throughout the winter. Small plants should not be covered with large mounds of leaves. Masses of leaves may begin to decay and smother the plant beneath them. Leaves may be pulled up around the stems in late fall but should not cover the entire plant. Temporary fences made of lath or snow fencing are effective in providing necessary windbreak and light shade.

Problems

Sunscald, scorch

Large-leaved evergreen rhododendrons are sometimes subject to sunscald during winter. This is most likely to happen if the plant did not receive ample moisture before freezing in fall. The exposed portions of the leaf (usually the central portion when the leaf was curled) may become brown. This may also appear on the edges of some leaves. To prevent scorch, plants should be well watered in November if rainfall has been sparse, protected from drying winds, mulched well and given some shade.

Iron chlorosis

If leaves turn yellow in sections between the veins, but the veins remain green, iron deficiency is the cause (Figure 3). If the entire leaf turns yellow with some browning, other problems are suggested.

Chlorosis may result from soil that is not acid enough, poor drainage, nematodes or other conditions that cause root or stem injury.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Typical symptoms of iron chlorosis.

Iron chlorosis can usually be temporarily controlled by spraying the foliage with an iron (ferrous) sulfate solution or with chelated iron. If iron sulfate is used, apply at a rate of one ounce per gallon of water. If a chelated iron product is used, follow the manufacturer's directions.

A slower but more permanent control can be obtained by applying iron to the soil rather than the foliage. Use 2 pounds iron sulfate per 100 square feet (1/8 cup per 10 square feet) or chelated iron according to directions. Conditions leading to chlorosis, such as poor drainage or alkaline soil, must also be corrected.

The application of 1-1/4 cups of iron sulfate per 100 square feet of bed area each fall appears to help harden growth for the winter and also help prevent iron chlorosis.

Insects and diseases

There are few insects or diseases that are troublesome on azaleas and rhododendrons. Those that normally occur can be easily controlled with all-purpose fungicides and insecticides. Prompt treatment as soon as the problem is noticed will be most effective.

Stem bark splitting

Rapid temperature changes and freezing can cause the bark to split and peel off. The stems do not usually heal and the branch dies above the injury. Death may not occur for one or two years. Winter protection may help, but generally the best remedy is to plant reliably hardy varieties or prune out affected branches of injured plants.

Rhododendron varieties

There are many beautiful rhododendrons. However, some are not reliably cold hardy or heat tolerant in our area. In general, more varieties may be grown in the milder climate of southern Missouri. The following selected varieties are some of the most reliable, although not always the most beautiful.

Of the many hybrids available, those derived from Rhododendron catawbiense, called Catawba hybrids, have the greatest hardiness. New varieties may be superior to those listed, but establishing their true adaptability takes many years. The collector may be willing to take risks with tender plants, but the beginner should always select varieties well adapted to the local environment.

- Album Elegans

Soft lilac fading to white, late flowering, a R. maximum hybrid. - Album Grandiflorum

White with a lavender tinge later fading to white. - America

Dark red with a ball-shaped flower cluster. Broad, bushy plant. - Atrosanguineum

Red with purple markings. Hardy. - Boule de Neige

White, early. Slow growing, but develops compact, large plant. - Catawbiense album

White flowers in round trusses. Narrow leaves, tall, vigorous. - Everestianum

Purplish-pink with green markings. Hardy. - Lady Armstrong

Deep purplish pink with red markings. - Mrs. Chas. S. Sargent

Deep rose spotted with yellow. Cold hardy. - Nova Zembla

Red flowers similar to America. Cold and heat tolerant (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Figure 4

Rhododendron 'Nova Zembla' is prized for its large trusses of showy, bright red flowers.

- Purple Splendor

Very deep violet purple with darker blotch. Very hardy. - P.J.M. hybrids

Lavender-pink flowers produced early in spring. Evergreen leaves small, turn purple in fall. Very hardy. - Roseum Elegans

Lavender pink with green markings. Endures temperature extremes. Best for beginner.

Evergreen azaleas

The evergreen azaleas need protected sites, and winter protection is necessary in many areas. In southeastern Missouri, the number of species and cultivars that may be grown increases and the need for protected sites and winter protection decreases.

Kurume hybrids

Most popular of the evergreen azaleas are the Kurume hybrids. They are popular for forcing in pots and for planting outdoors. In the southern United States, they become large, showy shrubs in the spring. They are fairly slow-growing plants with dense, twiggy growth. Hardiness varies considerably among the many varieties. Some of the hardiest cultivars are listed below.

- Coral Bells

Flowers are hose-in-hose (one blossom inside another), which gives the effect of semi-double flowers. Vivid pink color. Poor exposure will cause leaf scorch and twig die-back. - Hino-Crimson

Vivid red flowers on a low, cushiony plant. One of the most hardy. - Hinodegiri

Variety from which Hino-crimson was selected. Very similar but color not as intense red. - Pink Pearl

Large, hose-in-hose, soft pink flowers. Plant is low and spreading. - Snow

Large, single white flowers. Most reliable of white flowered Kurumes.

Gable hybrids

Gable hybrids were developed with hardiness in mind. Growth habit is similar to the Kurumes, but foliage may drop along a portion of the stem during winter, leaving only a few evergreen leaves at each tip.

Gable hybrids are sometimes called Kaempferi hybrids because one of the parents was the relatively hardy R. kaempferi. Although some are quite hardy, others are not, and no generalization as to hardiness of the Kaempferi hybrids can be made. R. kaempferi was also one of the parents used in the Glenn Dale hybrids. There are about 400 named varieties of Glenn Dale hybrids, but their hardiness has not been adequately tested in Missouri.

- Boudoir

Watermelon pink - Caroline Gable

Radiant pink - Dusty Rose

Pink violet - Elizabeth Gable

Double rose pink, late - Herbert

Purple - James Gable

Red, hose-in-hose - Louise Gable

Salmon pink, double - Purple Splendor

Dark purple - Rosebudsmall

Double flowers, rose-pink - Rose Greely

White, hose-in-hose, hardy - Stewartstonian

Orange-red, hardy.

Kaempferi hybrids tend to be more upright growing

- Atlanta

Light purple - Cleopatra

Light pink, early, tall - Fedora

Large, salmon rose.

Girard hybrids

Girard hybrids are a fairly recent introduction among evergreen azaleas suitable for colder climates. Their growth habits vary with variety, but generally most are fairly low and bushy. Leaves are bright green and some develop a reddish fall color. Although some older leaves may drop in the fall, leaf retention is greater than that of the Gable hybrids. Flowers are primarily single but fairly large. There are many fairly hardy varieties in this group. Here are a few distinctive varieties to consider.

- Girard Hot Shot

Large flowers in a deep orange-red to scarlet. Plants develop an orange-red leaf color in the fall for winter color. - Girard Renee Michelle

Flowers in a clear pink and large and showy. A very cold-hardy variety. - Girard Sandra Ann

Large purple ruffled flowers make this a distinctive variety. Plants are more upright than some Girard varieties. - Girard Rose

Large wavy rose-colored flowers are produced on somewhat upright plants. This is a very hardy variety with leaves that turn reddish in winter (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Figure 5

Girard hybrid azaleas produce abundant flowers on compact plants similar to Girard Rose, shown here.

- Girard Pleasant White

Flowers are white with a cream center. Although the single flowers of this variety are smaller than many, they are prolific. Plants are hardy and one of the last to bloom.

Deciduous azaleas

In areas where the evergreen azaleas are marginal, deciduous azaleas might best be selected (Figure 6). They have greater cold hardiness and provide a mass of color in spring. Different species vary widely in hardiness, however. Those normally found in nurseries will normally be the ones best suited to the area. Remember inexpensive plants are no bargain when it comes to azaleas and rhododendrons. Choose only vigorous plants of good varieties. Beginners should choose some of the old standards and later try some of the newer introductions.

Figure 6

Figure 6

Deciduous azaleas drop all their leaves in winter and flower before leaves fully develop in spring. Unlike the evergreen varieties, they can be found in orange and yellow.

Deciduous azalea varieties worthy of consideration include the following:

- Exbury (Knapp Hill) hybrids

Becoming extremely popular. Many varieties have good hardiness. Available in pastel shades ranging from cream, through pink to yellow and orange. Currently the favorite deciduous azaleas. - Northern Lights hybrids

Developed at the Universitiy of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum for winter hardiness. Plants and flower buds are said to have survived -40 degrees Fahrenheit. Plants are fairly compact and can grow to about 6 feet in height and width. Some suitable varieties are Orchid Lights, Rosy Lights, Spicy Lights, Northern Lights and White Lights. - Royal azalea (R. schlippenbachii)

A reliably hardy azalea with large, fragrant rose-pink flowers. Foliage has good autumn color, although may sometimes be burned by late summer heat. - Korean azalea (R. poukhanense)

Lilac-purple. Deciduous in cold climates. Low, spreading. One of the hardiest azaleas available. Early. - Mollis hybrids

Slightly more tender than Exbury, but much varietal variation. Colors mainly in yellow, apricot, orange, red. - Ghent hybrids

Available in a wide range of colors. Exbury hybrids are an improvement of the older Ghent hybrids.

Some of the native American deciduous azaleas may be grown in Missouri, but they are too diverse to be included here and many have not been adequately tested.

Original author: Christopher Starbuck, Department of Horticulture