The local production and marketing of food has reached a critical mass in the past decade. Increasingly, people are searching out food that not only is flavorful, healthy, and safe but that also supports their local community. Farmers are working hard to meet that demand and are taking advantage of the economic opportunities community-based, or local, food systems provide. Many farmers, particularly mid-sized (often called “farmers of the middle”) and small-scale producers, find that producing for and selling into a community-based food system is one of the only options left for them, as they lack the scale or financial resources to compete in a larger market. In recognition of the importance of local food systems, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has invested in several local food initiatives aimed at strengthening the relationships between farmers and consumers throughout the United States. In 2009, USDA recognized the energy around local foods with their Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food program (PDF) to integrate local foods knowledge into all parts of USDA. This effort has since found a home at USDA with its Agricultural Marketing Service.

This guide explores the concept of local food systems and provides resources to help farmers, consumers and communities develop food systems that provide for profitable, thriving farms and businesses; steward our natural resources; and strengthen community relationships in rural and urban Missouri.

A local food system expands the economic interactions between food producers and food consumers to include social relationships and environmental management centered on a particular place. A food system includes everything from personal and commercial food production to processing, marketing, distribution, retailing and consumption of food products, plus handling food waste. In a local food system, all of these activities are rooted in a particular place, whether a community, a metropolitan area or a region. A local food system may focus on particular ways of producing food or may develop alternative marketing channels that connect farmers and consumers. The social, economic and environmental aspects of local food systems are realized in various ways:

- Building social connections, spurring relationships and increasing shared knowledge between farmers and eaters

- Creating economic opportunities for food producers through the development of localized and regionalized marketplaces

- Strengthening environmental stewardship of food producers and distributors by reducing the use of natural resources needed to transport and market food items outside of their geographic area of origin.

Research suggests that, in general, community food systems have several attributes: They are community-centered, relational, place-based, participatory, healthy, inclusive of local people and supportive of the local economy.

Benefits of local food systems

The benefits of local food systems are much more than just the availability of food grown closer to home.

Consumers benefit from food that reaches their kitchens more quickly after harvest, which can help to ensure fresher flavor and decreased transportation costs. Buying locally grown food often means knowing the farmer or producer and having a clearer understanding of how food was grown or processed. In addition, buying local gives consumers an appreciation for the quality of seasonal food. Eating seasonal foods can raise awareness of healthier eating and may encourage the development of increased knowledge and skills in food preservation and cooking techniques, which in turn can further enhance the perceived value of locally grown seasonal produce.

Farmers benefit because personal relationships with local residents and regional purchasers may lead to alternative market opportunities that can increase sales and farm profits, creating a more diversified income for the farmer. By talking with local residents, farmers can identify new crops to raise to meet consumer demand and diversify their production and market opportunities for a more stable farming operation. Supporting local food systems supports local knowledge of farming techniques and provides opportunities for younger generations of potential farmers to enter farming on a small scale. The costs of large-scale or commodity farming can be prohibitive to new farmers, whereas beginning as a local food producer and building a business in small steps can be more affordable. Finally, producing and marketing food in a local food system requires skills in various production methods, face-to-face marketing, and new distribution models, and thus encourages farmers to increase their skills or recruit employees or family members into the farming business.

Communities benefit because supporting local food systems means supporting local economies. Buying from local farmers means food dollars stay in the community instead of flowing out to other states and countries. Local farms employ family members, neighbors, youth, and other community residents. Supporting local food systems also means supporting business development. Local food systems need productive, entrepreneurial, innovative farmers; community facilities for processing and packaging products; transportation and marketing infrastructure; and consumers, all of which help build a stronger local economy. Growing and purchasing food in a local system increases food safety and security because food grown in the community is less likely to be disrupted by transportation issues, large-scale foodborne illness outbreaks, weather, and high fuel costs.

Local food systems build community social structure by supporting the development of new personal relationships between farmers and their customers and new business relationships between farmers, grocery stores and restaurants. They can provide opportunities for developing social relationships at food-related events such as farmers markets, community gardens and u-pick farms. They also provide opportunities for local residents to talk with local farmers about production methods and to support environmental stewardship by spending their food dollars on products that may be grown more sustainably. Farmers can also teach people about the benefits of using organic methods, fewer chemicals and less tillage; and focusing on whole-farm systems that rely on natural processes to increase yields and reduce costs.

Building resilient communities

An additional benefit of local food systems is the opportunity for communities to be better prepared to withstand future challenges that could affect food supply. As our nation deals with increasing natural disasters, economic issues and international conflicts, the quantity and quality of food for U.S. consumers can be impacted significantly. In recent years, drought, flooding, tornadoes and late freezes have damaged many acres of food production land in the U.S. In addition, food safety scares with E. coli and other foodborne illnesses have sparked concern over the nation’s food supply. The COVID-19 pandemic also caused significant disruptions to the food supply, through food worker health safety issues, supply chain failures, processing backups, and empty store shelves. Communities that have a stronger local food supply — through local farmers, community gardens, food preservation and regional food hubs, or local product aggregation sites — are better positioned to maintain a stable, safe food supply in the event of a disaster. The local and regional foods systems' response to COVID was a collaboration focused on recovery and resilience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Communities with local food systems also know how to deal with local conditions and can better respond to challenges affecting food production in their local regions. Access to safe, local and consistent food creates more resilient communities able to respond and recover when challenges occur.

Tiers of the food system

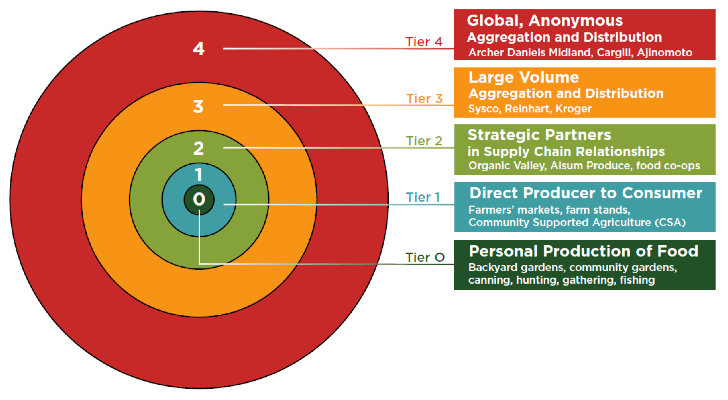

The Tiers of the Food System model provides a framework for thinking about food systems (Figure 1). In localized or regionalized food systems, the primary focus is on Tiers 0–2.

Tier 0: Personal production of food

The most local level of the food system is Tier 0. In this tier, we are connected in the most basic way to our food because we produce or forage it, cook or preserve it and then eat it. Tier 0 includes home and community gardens, hunting and fishing, and home food preservation. Home gardeners can grow their food based on their families’ needs and likes, harvest fresh from the garden or wild, increase their knowledge of the benefits of eating seasonally and help others recognize the skill and effort needed for food production. In community gardens, residents share gardening techniques and knowledge while growing food for their community in a shared setting. By preserving homegrown foods, families have more consistent sources of healthy produce throughout the year, may reduce their food waste and costs, and may increase the security of their food supply.

Tier 1: Direct relationships between farmers and eaters

Direct relationships between the people who grow the food (farmers) and the people who eat the food (consumers or eaters) characterize Tier 1 of the food system. In Tier 1, food producers are direct marketers, selling locally grown and produced foods at farmers markets, roadside stands and u-pick operations and through community supported agriculture (CSA) farms. Often regarded as the oldest form of commerce, farmers markets offer producers a way to sell small volumes of product at a price they set themselves. Roadside stands and u-pick operations offer an easier form of marketing for farmers, allowing them to move products from the field to an on-farm location for sale and to invite people onto the farm to make their purchases. CSAs offer the most complex example of a Tier 1 relationship between farmer and eater. Local residents invest in a farming operation or collective of farms, share the production risks and reap the benefits of the growing season. This form of relationship is more complex because it may require a signed contract, up-front payment for an entire season’s worth of product and on-farm working experiences for CSA members. The Tier 1 relationship between farmers and consumers often results in the development of lasting relationships and an exchange of knowledge that strengthens the local food system.

Tier 2: Moving beyond direct farmer-eater relationships

In Tier 2, the goal is to make locally or regionally produced food products available in as many outlets as possible because not every consumer has the time, knowledge or desire for direct relationships with farmers. Although many people enjoy participating in CSAs and farmers markets, others want the convenience of accessing locally and regionally produced foods in grocery stores, local restaurants or hospital and school food services. Some farmers prefer to produce a few products they can market in larger volumes, create niche markets or create value by developing a place-based food system. In Tier 2, locally produced food moves from the farm, either direct-marketed by the producer or via a distributor, through different marketing channels such as grocery stores, restaurants and institutional food services, such as those in schools and hospitals. Moving food through these channels benefits consumers by providing food from a farmer in places they can access easily in many different situations. Moving from direct-marketing relationships into Tier 2 is often called “scaling up local food systems” because farmers must produce a larger volume of food products packed, packaged or processed in ways that grocery buyers or distributors will accept. This scaling up can require new facilities for packing, processing and bringing together food products from multiple producers. Selling to grocery stores or institutional food services often requires farmers to develop new business skills or increase their operational capacity, and can require grocers, food distributors and food service directors to adapt their purchasing processes to locate sources of locally produced foods that may only be available seasonally.

According to Bower, Doetch and Stevenson (2010, 2), “A commitment to fairly sharing risks and profits across the supply chain sets Tier 2 businesses apart from larger counterparts. Tier 2 businesses typically embrace Tier 1 values, and their customers may be willing to pay more for adherence to these values. Products can often be traced back to the farms where they were grown, and farm identity and values are communicated to consumers through labeling and point-of-sale merchandising.” It is also important to develop identification systems that help consumers know that they are buying or eating food that is produced by farmers in their area and meets their demands for taste, quality and safety.

Tiers 3 and 4: Not just local food systems

Tier 2 relationships may not be appropriate for some farmers or food-based businesses, especially those that wish to deal in larger volumes of source-verified, differentiated agricultural and food products. Some of these opportunities and relationships can be identified in Tier 3. As Bower, Doetch and Stevenson (2010, 2) note, Tier 3 “involves highly efficient transactions by companies whose brands have widespread recognition. Efficiencies and lower prices are typically more important at this level than the values embraced in Tiers 1 and 2. While relationships with farms are usually lost at this level, Tier 3 businesses often work to cultivate positive relationships with their customers.” Farmers seek to build partnerships with distributors, processors, wholesalers and others in the business that fairly reward work across the value chain. They can maintain brand identity as members of a group collectively selling differentiated products like organic milk or humanely raised livestock. Nationally recognized businesses can source large volumes of consistent-quality products on which they can base their market position. A good example of Tier 3 is Vital Farms, which sources eggs from multiple family farms, and sells to Whole Foods, Schnucks, Target and other national grocery chains. Another example is U.S. Foods, a food supplier with a commitment to sourcing local food. However, Tier 3 source-verified suppliers are not stipulated to any geographic location and not all can meet the high-volume needs of a national chain.

Most food that is produced and consumed in the United States does not move through Tiers 0–3. Instead, most consumers, farmers and food businesses participate in Tier 4, which is based on producing large volumes of undifferentiated commodities for global markets. Raw and processed foods are traded within the global market and move anonymously within international trade partnerships. This tier is sometimes referred to as the conventional market and is discussed widely in extension resources.

Table 1. Benefits and challenges of participation in various tiers of the food system.

| Tier 0 | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Consumers |

|

|

| Farmers |

|

|

| Communities |

|

|

| Tier 1 | Benefits | Challenges |

| Consumers |

|

|

| Farmers |

|

|

| Communities |

|

|

| Tier 2 | Benefits | Challenges |

| Consumers |

|

|

| Farmers |

|

|

| Communities |

|

|

The role of community in local food systems

Rural communities

Although many benefits of local food systems are common for both urban and rural communities, rural communities can uniquely benefit from a vibrant local food system. Rural areas have a historic precedence for food production — whether on farms, home gardens, or foraging — and often the knowledge and infrastructure necessary for food production is more readily available from family members, neighbors and businesses. The history of agriculture in a community can also be used to support agritourism ventures, such as wineries and u-pick farms, and marketing of locally produced food to both residents and tourists. The increasing demand for locally produced food in urban areas provides a significant economic opportunity for rural farmers to increase food production for urban consumers located in the region. This encourages local entrepreneurs to develop production, marketing, processing and distribution operations that capitalize on this increased demand for locally produced food.

Local leadership, governments and nonprofit organizations can play a significant role in building a strong rural local food system. Access to fresh, healthy food can be a challenge for residents living outside city limits in more isolated areas of rural counties, with limited transportation options, fewer grocery stores and lower median incomes than other parts of the state. Community leaders can initiate improved transportation options, encourage and support development of farmers markets and other food venues near common service sites such as WIC clinics, rural hospitals, and senior centers, and provide in-kind services to develop community gardens. Supporting business development through policies and incentives can help new farmers in rural areas expand their businesses to reach more rural customers. Churches, garden clubs, community betterment groups and many other rural organizations can provide volunteer support for growing and sharing local food, and help develop farmers markets, community gardens and CSA operations.

A vibrant local food system can be an economic, social, healthful opportunity for rural communities.

Urban or metropolitan areas

Like clean water, unpolluted air and low crime, food is essential to an urban community’s health. A healthy urban food system supports local and regional food producers, creates rural-urban connections, builds localized economies, often promotes environmentally sustainable food production, seeks avenues to educate people about various production types, strives to increase access to healthy foods for all community residents, and seeks ways to make healthy foods the easy choice.

A healthy urban food system addresses many aspects of urban communities and urban life. Urban planners and business development groups often incorporate farmers markets and grocery stores into new developments as community attractions. Neighborhood groups, homeowners’ associations and social service organizations establish community gardens to increase access to healthy, affordable foods. Community organizations and health care providers advocate for healthy food projects and work to increase consumer access to fresh foods. Community governments seek new methods of building communities through support of local food production policies.

Recently, these activities have spurred growth in the area of urban food production known as “urban agriculture.” Consumer demand for fresh, local products has created business opportunities for residents to turn unused residential lots into urban farms. Schools have addressed healthy lifestyle education with schoolyard gardens. The business community has begun to consider how they can supply locally grown foods. Urban dwellers have pushed for changes in city zoning ordinances to allow for agriculture production, including animal agriculture and sales. These efforts are often noted as a method of fostering community within urban or metropolitan areas.

Yet, even as interest in urban agriculture development increases, it is unrealistic to believe that urban populations will become food secure, or self-reliant, through urban production alone. Urban-rural connections continue to be vital to the health of urban food systems. Urban populations are likely to continue developing relationships with rural food producers, and producers in rural communities are likely to continue finding market opportunities within the populations of urban communities.

Conclusion: Creating local food systems

Local food systems have many benefits for farmers, consumers and communities, but re-embedding food systems in local places takes a wide variety of knowledge, skills and efforts. Across Missouri and across the country, farmers and researchers are experimenting with new crops, new soil management techniques and new varieties and breeds that can help them meet the demands of local markets. Businesses are responding to the demand of local consumers and developing relationships with local farmers to spur increased wholesale availability of local products. Food distributors are developing new strategies to efficiently pick up and deliver locally sourced foods, while also helping farmers guarantee the safety of their food. Individuals, consumer groups and food advocates are creating change by demanding increased availability, becoming educated on the importance of eating local and advocating for healthier, fresh and local food products from farmers.

Local food systems also require different types of infrastructure – from small packing and grading sheds on farms, to food hubs and distribution models, to new storage facilities or retail spaces. Because local food systems are generally small-scale, it is important for participants to thoroughly investigate food safety regulations, economic incentives and tax structures to support their development. Education — from producing in hoop houses to cooking fresh foods and reducing food waste — will be a key component of strengthening and enhancing local food systems.

References and resources

- Bower, Jim, Ron Doetch, and Steve Stevenson. 2010. Tiers of the food system: A new way of thinking about local and regional food. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin.

- Day-Farnsworth, Lindsey, Brent McCown, Michelle Miller and Anne Pfeiffer. 2009. Scaling up: Meeting the demand for local food (PDF). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Extension.

- Diamond, Adam, and James Barham. 2012. Moving food along the value chain: Innovations in regional food distribution (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Marketing Service.

- Feenstra, Gail. 2002. “Creating space for sustainable food systems: Lessons from the field.” Agriculture and Human Values 19:99–106.

- Garrett, Stephen, and Gail Feenstra. 1999. Growing a community food system. Puyallup, WA: Washington State University.

- Goldstein, Mindy, Jennifer Bellis, Sarah Morse, Amelia Myers, and Elizabeth Ura. 2011. Urban agriculture: A sixteen city survey of urban agriculture practices across the country. Altanta, GA: Emory University, Turner Environmental Law Clinic.

- Hamm, Michael W., and Anne C. Bellows. 2003. “Community food security and nutrition educators.” Journal of nutrition education and behavior 35(1):37–43.

- Jensen, Jennifer. 2010. Local and regional food systems for rural futures. Iowa City, Iowa: Rural Policy Research Institute.

- Lyson, Thomas. 2004. Civic agriculture: Reconnecting farm, food and community. Medford, MA: Tufts University.

- Martinez, Steve, Michael Hand, Michelle Da Pra, Susan Pollack, Katherine Ralston, Travis Smith, Stephen Vogel, Shellye Clark, Luanne Lohr, Sarah Low, and Constance Newman. 2010. Local food systems: Concepts, impacts, and issues. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Trivette, Shawn. 2015. “How local is local? Determining the boundaries of local food in practice”. Agriculture and Human Values, Springer; The Agriculture, Food, & Human Values Society (AFHVS), vol. 32(3), pages 475-490.

- USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service. Local food research and development.

- USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service. Local and regional foods systems response to COVID.

Original authors

Mary Hendrickson, Sarah Hultine Massengale and Crystal Weber